ARTICLE

More 1980s than the 1980s:

Hauntological and Hyperreal Meanings of Synthwave Soundtracks

Mattia Merlini

Sound Stage Screen, Vol. 3, Issue 1 (Spring 2023), pp. 5–33, ISSN 2784-8949. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. © 2023 Mattia Merlini. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54103/sss14136.

A while ago, my interest in postmodern music revivals and adaptations bloomed as a relatively early listener of vaporwave and synthwave music, and I knew my understanding of such phenomena would benefit from an in-depth study of these two sibling genres born on the Internet and sharing a peculiar fascination with powerful visual aesthetics and a sort of obsession for the past. I was right. During my research, I noticed a recent spike in the academic study of vaporwave, [1] while synthwave looked like a relatively understudied subject, despite its favor in the popular press since its inception. [2] I could only find a handful of reliable, properly researched sources, especially those addressing synthwave’s retrofuturist qualities; and yet I had the feeling that this was just one side of the story. For instance, the use of synthwave music in cinema, and more generally its numerous connections and references to the cinematic realm, had not yet been given the attention it deserved. Back then, I had already watched several movies and tv series featuring synthwave as their main soundtrack; as a film music enthusiast, the relationship between synthwave and cinema struck me from the very beginning of my exploration and looked very much like one the most typical features of synthwave (as opposed to vaporwave). So, I decided to get in touch with one of the most relevant internet community populated by synthwave fans—i.e., the “Synthwave” Facebook group—asking for a list of movies featuring what they would term “synthwave soundtracks.” [3] Thus, I obtained hours and hours of promising material for a series of truly instructive and entertaining screening sessions, potentially leading me to the discovery of specific patterns and recurring significations in the use of synthwave music. Soon, the functions and connotations of synthwave soundtracks began to look like a quite intricate constellation—much more ramified than I expected—which is traditionally reduced to just 1980s-inspired electronic soundtracks for sci-fi movies, as the aesthetics surrounding much synthwave music suggests.

This paper attempts at redefining synthwave’s archetypical functions and connotations by focusing on its cinematic uses. To do so, I identify first- and second-order associations between cinema and synthwave music, analyzing four categories (association with sci-fi cinema, association with B-movies, age-synecdoche, and aesthetic mediation). While first-order associations can be made with respect to 1980s cinema, pointing directly to certain themes and peculiarities of the films in which such music is featured, second-order associations refer to the artifacts which established those connections in the first place, reflecting on them from a nostalgic and/or cosmetic perspective, and using them as a means to referencing specific (perceived) traits and characteristics of the 1980s and its (geek) culture. Both these orders of associations are involved in a dialectical process where cinema and music are always mutually implied (even in the case of non-cinematic synthwave music). In my analysis, I rely on various notions traditionally associated with postmodernism (such as “hauntology,” “retrofuturism,” and “hyperreality”) which will get a closer definition later in the paper. The outcome of my research, then, includes 1) a map of first- and second-order associations, and their possible meanings, in the cinematic realm; 2) a relativization of the mainstream connection between synthwave and sci-fi iconography and themes, a connection which I believe to be insufficient for a full understanding of the phenomenon’s wide spectrum of connotations and contemporary uses, which employ a wider palette of references to B-movies and geek culture from the 1980s.

Before delving into a proper analysis of the phenomenon, a couple of important premises:

1) according to most historiographical accounts, [4] synthwave—as a sort of postmodern, [5] nostalgic, and revivalist subgenre of electronic popular music, heavily inspired by certain kinds of music from the 1980s such as synthpop, post-punk (especially darkwave’s most electronic-oriented declinations), [6] and early video game music—has existed since the mid-2000s. [7] Because of this, I refer to the genre’s earlier musical models from the 1980s as “proto-synthwave.” In this category, I include different kinds of music (including those listed above) which are mostly independent from modern synthwave, but which were first associated with cinema and served as main inspiration for the present-day genre, both musically and in its cinematic connection.

2) under the label “synthwave” I include a range of diverse yet partially overlapping notions such as “outrun,” “retrowave,” and “futuresynth” as well as subgenres such as “slasherwave,” “darksynth,” “dreamwave,” or “chillwave.” [8] These forms of synthwave music are connected with artists like Carpenter Brut, College, Survive, Mega Drive, Dance with the Dead, Gunship, Com Truise, GosT, and Scandroid—all emphasizing, with their music, different aspects of the genre’s affordances. For instance, Perturbator’s music is often darker (thus representing the quintessential example of the darksynth subgenre), while Carpenter Brut’s is more aggressive and Gunship’s more accessible and catchier. Some of these artists also try to deviate more substantially from the mainstream: GosT’s music relies on black metal influences and Com Truise uses synthwave sounds to create atmospheres that are often sophisticated, ethereal, introspective, and quite unusual for the genre. Therefore, even though I understand that grouping all these different kinds of music under a single label might constitute a gross simplification, I do believe that over analyzing might impact negatively on general readability here. After all, all taxonomies tend to be more about the mood of the music than its style, which in this case does not vary significantly from subgenre to subgenre. Indeed, what makes this genre so easily recognizable is that its style flags are featured in almost every incarnation of synthwave. According to Philip Tagg, a “style flag” is a sign type that “uses particular sounds to identify a particular musical style and often, by connotative extension, the cultural genre to which that musical style belongs.” [9] Such stylistic features help establish a home style in the track (“style indicators”), or they can refer to a foreign style from a track that employs a different style (“genre synecdoche”). In the case of synthwave, we can identify as style flags the arpeggiated “fat line bass” sound from keyboards such as the Korg PolySix (1981) synthesizer and, more generally speaking, the use of vintage synthesizers such as Yamaha DX7 (1983), Roland Jupiter 8 (1981), Juno-60 (1982), Juno-106 (1984), and Oberheim OB-X (1979), plus the drum machines Linn LM-1 (1980) and Roland TR-808 (1980). [10] Production techniques are also recognizable, [11] and play a very important role in the definition of “retro” sound, [12] mixing together elements immediately perceived as 1980s trademarks (e.g., gated reverb snare) and those derived from present-day EDM, which tend to make the sound “thicker.” The subgenres’ labels also point to the relationship with specific film genres such as horror (e.g. slasherwave) and sci-fi (e.g. futuresynth), which is something that leads me to the next point.

Proto-Synthwave and First-Order Associations

Since many of these taxonomies highlight the connection of synthwave with film genres like science fiction and horror/slasher movies, now is a good time to start investigating proto-synthwave music and first-order associations, which have indeed a lot to do with sci-fi and B-movies (especially the horror kind). Science fiction is perhaps the genre most frequently associated with synthwave.

A few thoughts about the popularity of this association. First, even though the connection between sci-fi films and electronic music was no longer new in the 1980s, [13] it was around this time that synthesizers became “the sound of the future,” [14] being the finest piece of music technology available, capable of emulating virtually every acoustic instrument, but also of creating an entirely new world made by previously unheard sounds. [15]

Second, the biggest difference from the past was that the new films featured more popular electronic music rather than avant-garde electroacoustic works (e.g., Bebe and Louis Barron’s celebrated soundtrack for Forbidden Planet). [16] Indeed, already the 1970s saw the rise of the first stars of electronic popular music such as Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream, Brian Eno, and Jean-Michel Jarre, all of whom were making music appealing to a wider audience, thus facilitating the spread of that kind of music within the world of cinematic soundtracks as well. Electronic soundtracks became more palatable for general audiences (not least due to cross-promotion between films and songs), while also highlighting the advantage (from a producer perspective) of being less budget-demanding than most kinds of film music.

Third, several sci-fi movies featuring proto-synthwave soundtracks had a strong impact on popular culture. Particularly, two films made the association with sci-fi cinema even stronger, thanks to their success: Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), scored by Vangelis and featuring an unprecedented work of synthesized orchestration, [17] and Giorgio Moroder Presents Metropolis (1984), a version of Fritz Lang’s iconic film (1927) edited and restored by the Italian music producer who also wrote a new soundtrack, with an electronic style fitting the “mechanic imagery” at the film’s core. [18] Another important movie from that time is Tron (1982), with music by Wendy Carlos, whose visual style looks closer to what would become typical synthwave aesthetics. However, musically speaking, Tron’s soundtrack is quite different from the typical present-day synthwave sound, as it features a lot of Carlos’ typical “neoclassical” synth-playing style and orchestral arrangements. [19]

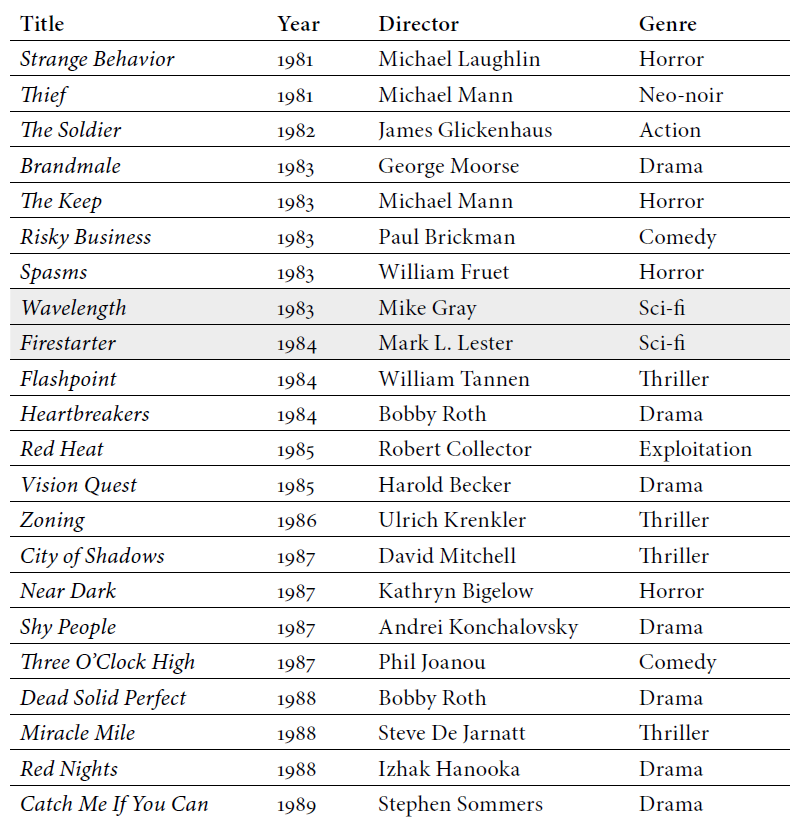

While these strong associations can help understand why synthwave music and sci-fi imagery are often paired, there is another first-order association still in need of investigation—i.e., Tangerine Dream’s soundtracks. True, the German electronic band was prolific in relation to both proto-synthwave music and sci-fi realm. [20] Yet, while apparently fitting within the first kind of first-order associations, Tangerine Dream’s soundtracks work better as an example of the second kind, since their relationship with sci-fi cinema should be put in proportion (see Table 1). The widespread tendency to overestimate Tangerine Dream’s musical contribution to sci-fi cinema is likely fostered by the fact that they were pioneers of the kosmische Musik movement. Not only the name of the movement, but also track titles (e.g., “Alpha Centauri,” “Sunrise in the Third System,” “Birth of Liquid Plejades”) and album artworks emphasized Tangerine Dream’s fascination for outer space from the very beginning of their career. This interest has been interpreted as a way of distancing—using a typically German musical means, elektronische Musik, only in a more popular way—from 1960s German popular music, which had not changed much since WWII. [21] Synthesizers became the voice of such urgency, and so Tangerine Dream’s music became one with cosmic sceneries well before it ended up soundtracking a variety of 1980s movies. The most celebrated soundtracks by Tangerine Dream—e.g., those for William Friedkin’s Sorcerer (1977) or Michael Mann’s Thief (1981)—, but also their albums that had nothing to do with cinema such as Exit (1981) and Hyperborea (1984), sound exquisitely synthwave; yet, ironically, most of the 1980s movies they recorded for do not fall into the category of sci-fi at all (see Table 1)—with notable exceptions to be found in Wavelength (1983) and Firestarter (1984) and in single futuristic, dystopic, and fantastic elements that sometimes infiltrate other non-sci-fi films.

Table 1. 1980s movies featuring Tangerine Dream soundtracks.

The same can be said of John Carpenter, who wrote the soundtrack for most of his own films, only a few of which can be defined as purely science fictional, although many of them involve fantasy or supernatural elements (e.g., monsters, imaginary dimensions, paranormal phenomena). His most iconic work is probably the soundtrack for Escape from New York (1981), and his only other soundtrack for a 1980s sci-fi film he directed is the one for They Live (1988), since The Thing (1982) was officially scored by Ennio Morricone. [22]

Thus, two of the most influential artists for contemporary synthwave—Tangerine Dream and John Carpenter—originally had much more to do with B-movies and geek culture than with sci-fi cinema. These examples highlight the insufficiency of first-order associations with sci-fi in encompassing the whole spectrum of associations between cinema and proto-synthwave music. Therefore, let me introduce a new first-order association: that between proto-synthwave and B-movies. Indeed, proto-synthwave music often appeared not only in sci-fi films but also in horror and action movies, all typically belonging to the category of B-movies. There is often a lowbrow, sometimes even “cheap” (if not altogether kitsch) connotation in a lot of proto-synthwave music, just as lowbrow are many B-movies featuring such music. A perfect match: inexpensive music for low-budget cinema; popular, commercial, easy-listening, and “easy-watching” products for geeks and nerds. An association so powerful that its consequences are noticeable in present-day second-order associations as well.

Hauntology, Retrofuturism, Hyperreality, and the Rise of (Post-)Modern Synthwave

Fast-forward to some thirty years later. The cultural setting has changed quite a bit and we are in the postmodern era. Modern synthwave, which emerged around the mid-2000s, starts to gain popularity over the early 2010s. [23] 2011 looks like a truly significant year: [24] it is the year in which Nicolas Winding Refn’s film Drive—featuring Kavinsky’s track “Nightcall,” arguably synthwave’s first “hit song”—is released. The following year, the Swedish video game Hotline Miami (2012) featured several synthwave artists as part of its soundtrack (e.g., M.O.O.N. and Perturbator), thus “greatly contribut[ing] to the expansion of synthwave.” [25] Along with the music, the game’s visual style made more and more frequent apparitions on the internet—fancy cars, retro commercial titles (Out Run, Street Fighter), exposed polygons, [26] purple-dominated dark visual atmospheres (including primary colors blue and red), and a general glossy graphic style stemming from 1980s film posters (e.g., Blade Runner and RoboCop). [27] Synthwave typographic layouts became quite standardized as well: “thick, 3D styled, and textured in a metallic way, chromed with mountain or desert reflections, and sometimes a few luminous halos bring elements of brilliance to the top of some letters.” [28]

Such aesthetic standards and the long history of associations with sci-fi contributed to the definition of synthwave as a genre constantly implying the idea of a future rooted in the past—an imaginary future which never came true. [29] Postmodern thought have abundantly addressed these kinds of phenomena, with Mark Fisher as one of the most influential scholars in the field. Fisher has written extensively on hauntology, [30] a concept that is closely related to synthwave and several other kinds of present-day music. The term designates a specific trait of the postmodern condition: its perpetual anachronism, namely its constantly being “haunted” by the specters of the past, by the “no longer” and the “not yet.” We cannot let the past go, and we cannot get rid of old forms, now that the waning of history has become reality, and thus we are stuck in an ongoing act of nostalgic repetition. The past persists, from beyond the grave, in a state that is neither dead nor alive, spectral, and incapable of letting the present be. Fisher describes this condition by paraphrasing Derrida:

Haunting, then, can be construed as a failed mourning. It is about refusing to give up the ghost or—and this can sometimes amount to the same thing—the refusal of the ghost to give up on us. [31]

He also draws explicitly from Fredric Jameson’s thought:

Fredric Jameson described one of the impasses of postmodern culture as the inability “to focus our own present, as though we have become incapable of achieving aesthetic representations of our own current experience.” The past keeps coming back because the present cannot be remembered. [32]

In this context, the sounds and colors that characterized B-movies from the 1980s (and especially the first-order association with sci-fi) acquire a bittersweet taste, a hauntological feeling contaminated with retrofuturism, as a kind of nostalgia for an image of the future that was implied in the popular culture of the past, where it now lies forsaken, thus blending the “not yet” and the “no longer” together. [33] In this “dyschronia” or “temporal disjuncture” (to use Fisher’s words) we are fascinated by, if not obsessed with, past images of a possible future—which is now lost, overwritten by our present. This “retrofuturistic” feature of synthwave qualifies the latter genre as quintessentially hauntological, since the nostalgia involved in modern synthwave sends us back to an image of a lost past and a lost future at the same time; for the past is always lost, and the future imagined in the 1980s never existed outside the fiction soundtracked by the proto-synthwave classics.

But that image of a future from the past still exists in its own way. Being created by mediatized fantasies, mass-distributed products, and kept alive by the self-referential narrations of mass media, that fictional world has become “more real than real,” as did the collective and idealized memory of the time in which these narrations were first conceived—i.e., the 1980s. To follow Jean Baudrillard’s well-known notion of “hyperreality” we can say that, in the postmodern age, reality itself has undergone a process of mediatization, in which signs and images experienced through media (especially TV, at the time Baudrillard was writing) lose their status of representations, thus being actualized in a world of simulation that we experience as (hyper)real. [34] This kind of proxy-reality, constantly hyped and enacted by mass media narrations, ends up occupying the highest throne in the hierarchy of what we perceive as “real.” It becomes our basic way of understanding the phenomena around us and obfuscates the boundaries between reality and imagination. Though phantasmatic and ethereal, the specters described above do not stop being active within our collective imagination, resulting in a blurred image in which present, past, and (imaginary, science-fictional) future overlap.

Second-Order Associations: 1. Synthwave as an Age-Synecdoche

Such pseudo-hallucinatory experiences thus result in second-order associations. The connection between modern synthwave and themes like technology, the future, and the metropolis are probably the most immediate one could think of. Yet, similarly to the past, today synthwave is not exclusively linked to science fiction. Ironically, it is easier to find sci-fi imagery in the artworks, lyrics, and concepts of non-cinematic synthwave music (Perturbator probably being the clearest example). [35] Science fiction (especially its dystopic and cyberpunk declinations) has permeated the realm of synthwave clichés, perhaps making “autonomous” synthwave music the most accurately “retrofuturistic” one. Nevertheless, as a hauntological genre, synthwave’s ties to the past are even more noticeable when people involved in the revivalist process can relate to the geek culture of that period—being fascinated by science fiction, fantasy, “cult” movies, video games, and comic books, often taking that passion to a higher level by reproducing their favorite iconic symbols via graphic arts, action figures, roleplaying, and so on. [36] This does mean that only those who lived and experienced that era (coinciding more or less with the so-called Generation X) can fall under the fascination of products that try to revive the specific feeling of the 1980s popular culture. The cultural artifacts from that era are still around us, anyone can experience and love films from the 1980s, and anyone can be fascinated by the specific aesthetics from that age, or at least by those traits which the revival of that age decided to take into our times. [37]

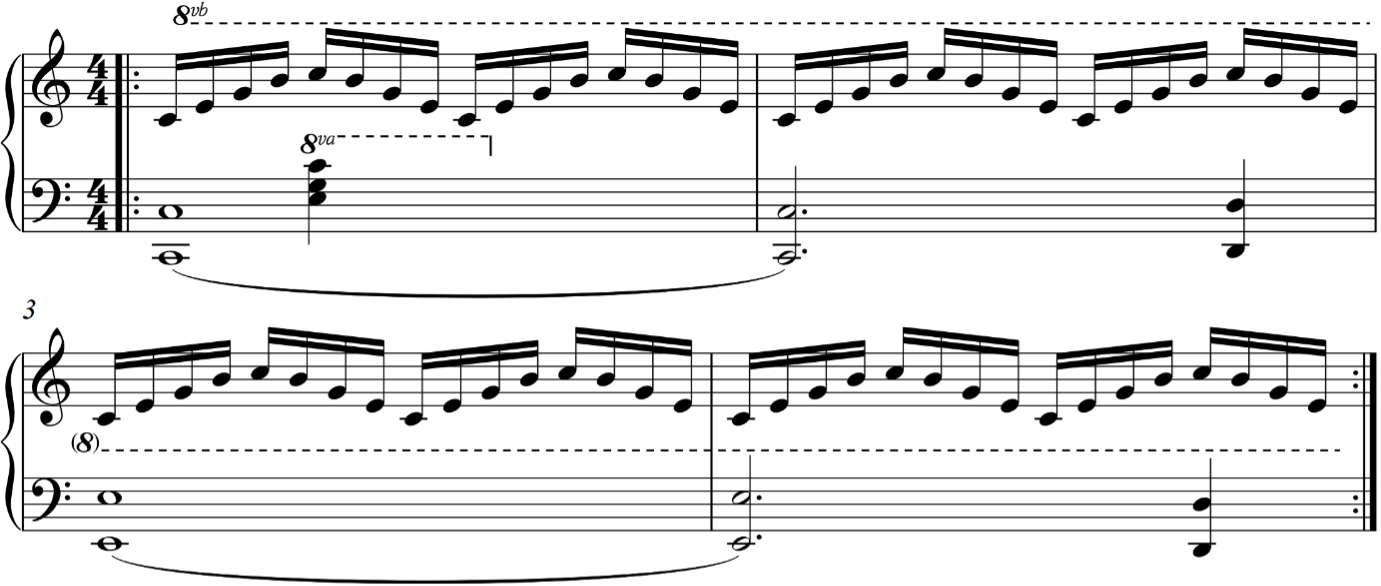

These are the main coordinates for the first second-order association between synthwave and contemporary cinema, in which synthwave soundtracks serve the purpose of bringing back to life not just a style of music, but rather the whole “1980s era” geek culture portrayed in the movie. Thus, music becomes a synecdoche for an age (form now on “age-synecdoche”): it works as a part to reference the whole—the part being music and the whole being 1980s geek culture. That era can be represented in both explicit and implicit ways, as we can witness from two examples. First, the Netflix series Stranger Things (2016-ongoing) celebrates explicitly the 1980s geek culture and attempts at reviving the feeling of watching a B-movie from that era, [38] thanks to the extensive use of narrative topoi from that world and the inclusion of hit songs from the same decade. [39] The story is mainly narrated from the point of view of a group of kids and deals primarily with mysteries, missing people, monsters, supernatural powers, and conspiracies (plus the inevitable love stories). Composers Michael Stein and Kyle Dixon are both members of the synthwave band Survive, so their presence serves the series’ hauntological aim of reviving the 1980s quite spontaneously. [40] This is made abundantly clear from the very beginning of each episode, as the opening theme is one of the most synthwave-ish tracks of the entire soundtrack (figure 1). [41]

Fig. 1 – An excerpt from the Stranger Things opening theme

The leading voice here is an arpeggiated figure over a Cmaj7 chord played by an Oberheim Two Voice synthesizer throughout the whole track. [42] The quality of the sound is gradually modified by an ever-changing cutoff filter, while a deep pulsating kick drum sound (not included in Figure 1) keeps the track rhythmically engaging. The main melody is played by the bass sound (a Roland SH-2) moving around C and E, harmonically characterizing the theme. In fact, the main arpeggio can be interpreted either in the tonal area of C major (with an added major seventh) or E minor (with an added minor sixth) depending on the bass note being played, and so the track oscillates modally to fit the overall “moody” sound. The same duality can be found in the series, alternating playful and pleasantly nostalgic moments with creepy and dark sequences. With additional synth pads (probably played on a Prophet 5) and sweeping effects, the overall impression of being hit by a “wave” of synths becomes even stronger.

While Stranger Things includes sci-fi elements, its primary goal is to revive the peculiar “1980s feeling” as a whole[43]—or, at least, to wink at the geeky popular culture from that time. Supernatural powers and creatures are but one of the ingredients of an entirely nostalgic operation. This aesthetic project is pursued by giving the soundtrack a significant role in the process: synthwave works here as a synecdoche for an entire era, and especially for its geek culture and lowbrow connotations; both things that were already present in the first-order associations, which now get remediated by the music. Here, the reference is explicit, given the years in which the story is set, the music the characters listen to, the abundant citations, and the general celebration of geek culture and B-movies from the 1980s. Other relevant examples of this process can be found in less-known products, all set in the 1980s and featuring synthwave soundtracks: Summer of 84 (2018), with music by the Canadian band Le Matos, an independent film in which the young protagonists try to solve mysteries; the quintessentially nostalgic episode “San Junipero” from the Black Mirror series (music by Clint Mansell); the series Halt and Catch Fire (2014–2017), possibly not so much interested in nostalgia as in featuring music by Tangerine Dream’s Paul Haslinger.

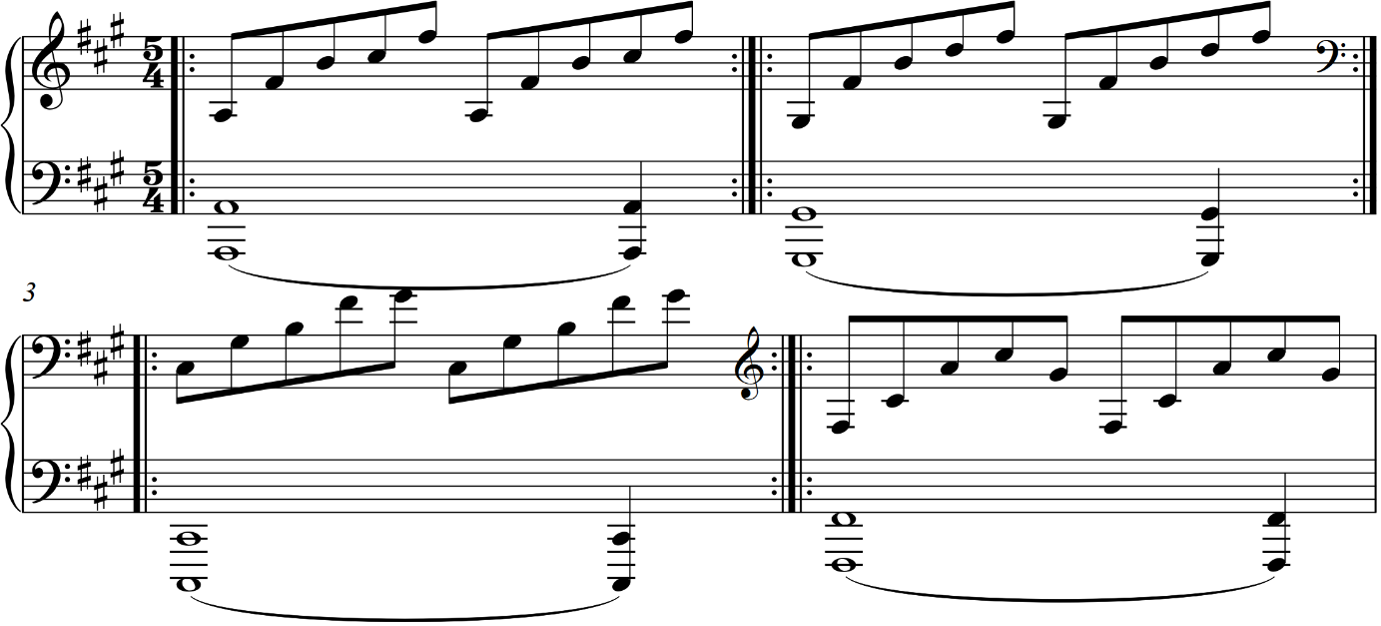

On the other hand, an implicit reference to the 1980s can be found in It Follows (2014), a horror film directed by David Robert Mitchell and scored by Richard Vreeland—better known as Disasterpeace—with a style that hybridizes classic synthwave with idiomatic traits of horror film music. The film deals with the story of Jay, a teenage girl trying to get rid of an entity whose potentially mortal curse is transmitted via sexual intercourse from victim to victim. Set in an unspecified time, the film nevertheless hints at the past through the celebration of its main cinematic influences—i.e., classic horror-slasher movies from the late 1970s and ’80s, especially those directed by John Carpenter and George Romero, [44] which occupy “a space within our collective, pop cultural, consciousness.” [45] As many of those films do, It Follows tells an apparently straight-forward, compelling, and entertaining story in an aesthetically effective way, and with lots of subtexts and possible further levels of interpretation (in this case, an allegoric tale about AIDS, [46] referencing the decade sadly remembered as the “golden age” of the disease), without ever sacrificing the lowbrow connotations of the film as an entertaining product of popular culture. It Follows’ reverential and cinephile use of synthwave music reinforces the celebration of a certain kind of 1980s “cult” films to which Mitchell owes a huge debt and stages an intertextual game that is entirely played within the field of cinema, in which authors, genres, and manners of doing popular films become more important than the connotations of the entire age, of which only a small portion is now being simulated. An example is provided by the track “Detroit” (figure 2), played with high priority in the mix during a scene in which the protagonists drive through the streets of the eponymous city, contemplating the urban (at times, eerie) landscape.

Fig. 2 – Excerpt from the track “Detroit”

As with the previous example, an arpeggiated synth line is the main protagonist of the track, and there is not much more going on, except for some filter modulation and the unusual time signature (5/4, after an introduction in 4/4) emphasizing a ghostly sense of instability and tension (also tangible in the harmonic structure). More importantly, the music is featured during a scene filled with explicit references to Carpenter’s movie Halloween (1978) [47] —just as several sections of the film are a tribute to the cinema of the past. The link between the two eras is authenticated by a soundtrack referring directly to the 1980s, especially to the old B-movies featuring the same kind of music. After all, this is another way (less direct, more subtle, and maybe even exoteric, but just as hauntological) of celebrating a long-lost culture, reviving it through a music style that was associated with it in the 1980s and that is now capable of remediating that same era in the form of “age-synecdoche.” [48]

Another example in this direction is Turbo Kid (2015), a Canadian film by the same directors responsible for Summer of 84 (see supra) François Simard and the Whissell Brothers. The film is not set in the 1980s, but rather in an alternate 1997; [49] yet, the plot, special effects, cast choices, and—of course—synthwave music are all open tributes to “cult” (B-)movies from the 1980s. The same could be said of other (mostly thriller/horror) films featuring synthwave music such as Starry Eyes (2014) or Bloodline (2018), the latter also clearly referencing synthwave imagery on the movie poster (but not so much in the cinematography), which shows a picture of the protagonist with highly saturated and contrasted blue and red lighting. In Maniac (2012), synthwave music is also motivated by it being a remake of a 1980 film, while Cold in July (2014) is set in 1989. Sometimes, this way of referencing 1980s geek culture becomes grotesque and ironic, as it happens with Kung Fury (2015), a crowdfunded, over-the-top film that both celebrates and mocks the archetypical 1980s action/sci-fi film—featuring, not surprisingly, tons of synthwave music. In the world of video games, a similar example can be found in Far Cry 3: Blood Dragon (2013, music by Power Glove), a first-person shooter set in a (retro-)futuristic world featuring all the aesthetic and musical archetypes of synthwave.

Second-Order Associations: 2. Synthwave as Aesthetic Mediator

Sometimes the reference to the 1980s can just be “cosmetic,” which brings me to the other category of second-order associations—i.e., synthwave as aesthetic mediator. In these cases, the presence of synthwave music in a movie works to strengthen references to canonical visual styles traditionally associated with synthwave (see supra). Like the other second-order association, this one can be chronologically located around the first years of the 2010s. One of the first possible examples in this direction comes again from the world of Tron: Tron Legacy’s (2010). Yet, despite the movie’s mediatic resonance (but just as with the original Tron, 1982) the equation does not seem complete: its soundtrack, composed by Daft Punk, is in fact largely symphonic, and even when it is entirely electronic it tends to sound more like generic EDM than synthwave—as it happens with the soundtrack for Gaspar Noé’s Irréversible (2002), composed by Daft Punk member Thomas Bangalter, or with a far less known Canadian film, Beyond the Black Rainbow (2010), that mostly employs synths to create an appropriate ambience for the surreal atmospheres and the overall slow pace of the film, but also features more intelligible tracks that are immediately recognizable as synthwave.

A more promising candidate for the role of prototype of this last second-order association is Drive (2011) by Nicolas Winding Refn: [50] with that film, the Danish director began what I would call the “synthwave phase” of his cinema, also contributing to synthwave’s popularity by using the track “Nightcall” by Kavinsky for the opening credits scene (as previously mentioned). Refn had already shown a certain interest in surreal atmospheres and highly saturated colors (especially red and blue, given the director’s color blindness) [51] in the most psychedelic scenes from Fear X (2003) and Valhalla Rising (2009), but it was only with Drive that he began to employ such visual solutions systematically and added one last ingredient to his mature style: synthwave soundtracks. Drive (2011), Only God Forgives (2013), and The Neon Demon (2016) are his three films—to which we could add the miniseries Too Old to Die Young (2019)—that feature that kind of music and, at the same time, take Refn’s visual aesthetics to a whole new level. The three films can be conceptually grouped not only after some of their shared themes, [52] their dark atmospheres, or their generally slow pace, but also for their visual hyper-aestheticization (the obsession with beauty is also the main theme of The Neon Demon), the saturation of colors (red and blue in particular), and the presence of synthwave music mostly composed by Cliff Martinez.

Martinez’s artistic output reaches far beyond his work for Refn. In fact, after quitting as the drummer for Red Hot Chili Peppers, his career as a film music composer took off with his collaboration with Steven Soderbergh. [53] The tracks were mostly in the style of electronic music, but things started to change with Drive in 2011 and, just a few months after, with Contagion, another Soderbergh movie with sound much more akin to synthwave’s standards. Even though there is a lot more in Martinez’s works than mere musical signposting, references to synthwave are strongly emphasized, especially in the music he composed for Refn.

Fig. 3 – The main arpeggio in ‘Wanna Fight?’

The track “Wanna Fight?” from the Only God Forgives soundtrack is a good example not only of how synthwave is used in Refn’s recent films, but also of how Martinez’s soundtracks often go beyond the pure adherence to the genre’s standards—without ceasing to sound entirely idiomatic. We hear a synth arpeggio with modulating filter (figure 3) playing throughout the whole track, and this is the “safe” part. What is unexpected is the presence of organ chords coming in after the first seconds of the track, briefly followed by some clean electric guitar sounds. The two “intruders” could be seen as referencing solutions typical of soundtracks for the Western genre and, in fact, the music here accompanies a duel between the protagonist and one of the villains, with a very slow introduction in which the two characters move around and stare at each other—a visual style closely associated with spaghetti Westerns (figure 4, top left and top right). These same musical elements, with their fluctuating ways of engaging with the arpeggiated synth, play with the listeners’ perception of rhythm, from 3/4 to 6/8 meter at around minute three of the track. But what is more important is the scene’s cinematography: red is the dominant color, mostly due to the neon lights and the oriental decoration in the background (figure 4, bottom left), while blue is featured as part of the protagonist’s outfit and in those shots where the protagonist’s mother approaches the room coming from a dark corridor, while the two men fight. There is an abundant use of slow motion and care for symmetry, while at times we can also see the statue of a man in a fighting pose (more likely a reference to vaporwave than synthwave) in a shady setting, only illuminated by suffuse red and yellow lights (figure 4, bottom right).

Fig. 4 – Frames from the ‘Wanna Fight?’ scene

Another scene with similar visual aesthetics is set in a bar and features again synthwave-ish music at loud volume. The music here is much less idiomatic: we hear an analog soft synth pad playing a sort of aethereal line at slow pace, while the protagonist is imagining an interaction with the female character standing in front of him (figure 5, top right, bottom left). Props and male actors are soaked in red (and, to a minor degree, blue) lighting (figure 5, top left), while the two women depicted in the scene are distinctively dressed in blue (figure 5, bottom left and bottom right). Despite the quasi-idiomatic kind of synthwave presented here, the scene emphasizes the association between synth(wave) music and a peculiar visual style.

Fig. 5 – Frames from the bar scene

Thus, another second-order association takes shape. Refn is not interested in referencing the 1980s in his movies, nor is there an explicit or implicit connection with geek culture or filming technique from that decade—also given the fact that Refn’s cinema tends to be much more highbrow-oriented compared to previous examples. What we can find in his films is the saturation and the aesthetic perfection of an idealized version of 1980s films (or perhaps their promotional material), hauntologically coming back from the world of the dead in its strongest incarnation. The postmodern city outlook, neon lights, the promise of a wealthy future… all worn inside out, playing in reverse, and brought to its extreme consequences, but still there: more 1980s than the 1980s. [54]

Other examples of this kind of second-order association include: the anime series Devilman Crybaby (2018), which features a good number of synthwave tracks (although other genres are represented as well), especially in its many “over the top” scenes, colorful to the point of becoming psychedelic; the sci-fi horror movie Beyond the Black Rainbow (2010), with a visual style that looks like an overcharged and saturated version of Tarkovsky, and with most non-noise music sounding definitely synthwave; Bliss (2019), a film dominated by green, blue, and red hypersaturated shots, featuring a kind of synthwave soundtrack that is often distorted and decomposed to better resonate with the mood of the hallucinatory and excessive plot of the film; the Malaysian neo-noir Shadowplay (2019), filled with synthwave music and shots often sticking to the abovementioned visual imagery; VFW (2019), a horror film shot almost completely indoors, with a high degree of red and blue neon lighting. All these (re)incarnations and celebrations of the 1980s go far beyond what the original phenomenon was. They refer to a hyperreal version of that decade that dwells in our imagination and is being rebuilt day after day by such products. There is no nostalgia here, nor mockery or parody. Just the elegance and aesthetic emphasis that, especially when paired with synthwave music and its history of associations, references the shiny and glossy semblance of a hyperreal, mediatized version of the 1980s.

So, while the description I provided of the four associations may not be exhaustive of all the possible functions and connotations of synthwave music in cinema, it will at least serve to discourage simplistic views of a phenomenon which proved multifaceted, even to my initial expectations. Far from being just an adequate soundtrack for colorful sci-fi B-movies, synthwave builds its essence in dialogue with a wider array of cinematic references and with their role as representatives of a particular culture, its agency, and its visual art—or, at least, a mediatized version of all of this, namely their mortal remains still accessible to us all.

In this paper, I have focused on two eras—the 1980s and the 2010s—identifying archetypical relationships between cinema and synthwave. I argued that we can isolate at least four of them. Two first-order associations were established in the 1980s: the first connects proto-synthwave music with sci-fi contexts through the impact of particularly successful sci-fi films on the later modern synthwave aesthetics (from the “classic” use of electronic music in science fiction and from the technological connotations of the music and the synthesizer as an instrument); the second relates synthwave music to lowbrow “popular” genres, especially B-movies which became cult for geeks.

The other two kinds of second-order associations are a product of the 2010s: the first interprets synthwave as a synecdoche for the 1980s as an era and its “geeky” popular culture, sometimes referring to certain cinematic authors, genres, and styles, while working at an intertextual level to reference a peculiar cinematic style. The second concerns synthwave acting as an “aesthetic mediator” for a visual style inspired by standardized use of colors, shapes, and atmospheres from the 1980s. Both these second-order associations can be used for ironic, nostalgic, or even just “cosmetic” purposes—which can also be mixed together. All these connections set cinema as a constant implication in every kind of synthwave music, including non-cinematic. From this perspective, modern synthwave music, regardless of its purposes, is essentially remediating 1980s popular culture with only little interest in the accuracy of such simulating activity—thus leading to the paradox of creating a sort of postmodern hyperreality that looks and sounds “more 1980s than the 1980s.”

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Carlo Lanfossi for his patience and editorial help, Maurizio Corbella and Guglielmo Bottin for their suggestions, and Emilio Sala for his trust in my work. Many scholars who participated in the “Musical Retrofuturism in the 21st Century” Symposium (August 2022) gave insightful feedbacks to the seminal version of this research. Finally, I express my gratitude to the “Synthwave” Facebook Group for suggesting many of the films listed in this paper, and especially to Peter Vignold for a truly inspiring chat.

(films featured exclusively in Table 1 are not included here)

Beyond the Black Rainbow, dir. Panos Cosmatos. CA, 2010.

Blade Runner, dir. Ridley Scott. US/HK, 1982.

Bliss, dir. Joe Begos. US, 2019.

Bloodline, dir. Henry Jacobson. US, 2018.

Chariots of Fire, dir. Hugh Hudson. UK, 1981.

Cold in July, dir. Jim Mickle. US, 2014.

Contagion, dir. Steven Soderbergh. US, 2011.

Devilman Crybaby, dir. Masaaki Yuasa. JP, 2018.

Drive, dir. Nicolas Winding Refn. US, 2011.

Escape from New York, dir. John Carpenter. US, 1981.

Fear X, dir. Nicolas Winding Refn. DK/US, 2003.

Firestarter, dir. Mark L. Lester. US, 1984.

Forbidden Planet, dir. Fred M. Wilcox. US, 1956.

Halloween, dir. John Carpenter. US, 1978.

Halt and Catch Fire, cr. Christopher Cantwell and Christopher C. Rogers. US,

2014–17.

Interstellar, dir. Christopher Nolan. US/UK, 2014.

Irréversible, dir. Gaspar Noé. FR, 2002.

It Follows, dir. David Robert Mitchell. US, 2014.

Kung Fury, dir. David Sandberg. SE, 2015.

Maniac, dir. Franck Khalfoun. FR/US, 2012.

Metropolis, dir. Fritz Lang. DE, 1927.

Midnight Express, dir. Alan Parker. UK/US, 1978.

Only God Forgives, dir. Nicolas Winding Refn. DK/FR, 2013.

RoboCop, dir. Paul Verhoeven. US, 1987.

“San Junipero,” dir. Owen Harris. In Black Mirror (S3, E4), cr. Charlie

Brooker. UK, 2011–19.

Shadowplay, dir. Tony Pietra Arjuna. MY, 2019.

Solaris, dir. Andrei Tarkovsky. RU/DE, 1972.

Solaris, dir. Steven Soderbergh. US, 2002.

Sorcerer, dir. William Friedkin. US, 1977.

Starry Eyes, dir. Kevin Kölsch and Dennis Widmyer. US, 2014.

Stranger Things, cr. The Duffer Brothers. US, 2016–19.

Summer of 84, dir. François Simard, Anouk Whissell and Yoann-Karl Whissell.

CA, 2018.

The Neon Demon, dir. Nicolas Winding Refn. DK/FR/US, 2017.

The Running Man, dir. Paul Michael Glaser. US, 1987.

The Terminator, dir. James Cameron. US, 1984.

The Thing, dir. John Carpenter. US, 1982.

They Live, dir. John Carpenter. US, 1988.

Thief, dir. Michael Mann. US, 1981.

Too Old to Die Young, dir. Nicolas Winding Refn. US, 2019.

Tron, dir. Steven Lisberger. US, 1982.

Tron: Legacy, dir. Joseph Kosinski. US, 2010.

Turbo Kid, dir. François Simard, Anouk Whissell and Yoann-Karl Whissell. CA,

2015.

Valhalla Rising, dir. Nicolas Winding Refn. DK, 2009.

VFW, dir. Joe Begos. US, 2019.

Wavelength, dir. Mike Gray. US, 1983.

Ludography

Far Cry 3: Blood Dragon. Ubisoft Montreal. PC/PlayStation 3/Xbox 360, 2013.

Hotline Miami. Dennaton Games. PC/PlayStation 3–4-Vita, 2012.

Out Run. Sega-AM2. Arcade, 1986.

Street Fighter. Capcom. Arcade, 1987.

Discography

Cliff Martinez, “Sister Part 1.” Only God Forgives, Milan Records, 2013.

Cliff Martinez, “Wanna Fight?.” Only God Forgives, Milan Records, 2013.

Daft Punk, “Giorgio By Moroder.” Random Access Memory, Columbia, 2013.

Disasterpeace, “Detroit.” It Follows Original Motion Picture Soundtrack,

Milan Records, 2015.

Kavinsky, “Nightcall.” Outrun, Record Makers, 2010.

Kyle Dixon & Michael Stein, “Stranger Things.” Stranger Things, Vol. 1,

Lakeshore, 2016.

Tangerine Dream, “Alpha Centauri.” Alpha Centauri, Ohr, 1971.

Tangerine Dream, “Birth of Liquid Plejades.” Zeit, Ohr, 1972.

Tangerine Dream, Exit, Virgin, 1981.

Tangerine Dream, Hyperborea, Virgin, 1983.

Tangerine Dream, “Sunrise in the Third System.” Alpha Centauri, Ohr, 1971.

[1] Vaporwave will only be mentioned sparsely in this paper; further readings on the subject, which can help in framing synthwave into wider context, are: Georgina Born and Christopher Haworth, “From Microsound to Vaporwave: Internet-Mediated Musics, Online Methods, and Genre,” Music and Letters 98, no. 4 (2017): 601–47; Ross Cole, “Vaporwave Aesthetics: Internet Nostalgia and the Utopian Impulse,” ASAP/Journal 5, no. 2 (2020): 297–326; Laura Glitsos, “Vaporwave, or Music Optimised for Abandoned Malls,” Popular Music 37, no. 1 (2018): 100–118; Padraic Killeen, “Burned Out Myths and Vapour Trails: Vaporwave’s Affective Potentials,” Open Cultural Studies 2, no. 1 (2018): 626–38; Raphaël Nowak and Andrew Whelan, “‘Vaporwave Is (Not) a Critique of Capitalism’: Genre Work in An Online Music Scene,” Open Cultural Studies 2, no. 1 (2018): 451–62; Sharon Schembri and Jac Tichbon, “Digital Consumers as Cultural Curators: The Irony of Vaporwave,” Arts and the Market 7, no. 2 (2017): 191–212.

[2] Several of the richest articles located on the internet will be referenced throughout the article. In addition, I suggest reading Christian Caliandro, “Dreamwave, Synthwave, New Retro Wave. Appunti sulla nostalgia sintetica,” Artribune, March 8, 2015; Jon Hunt, “We Will Rock You: Welcome to the Future. This Is Synthwave,” l’étoile, April 9, 2014 (site discontinued, available through Internet Archive here).

[3] Most of those movies will be referenced throughout the paper.

[4] Which, at present, are mostly compiled by fans and journalists, as mentioned above.

[5] Synthwave’s relationship with postmodernism—already partially explored in Martynas Kraujalis, “Synthwave Muzikos Stilius: Keistumas Ir Hiperrealybė” (master’s thesis, Lietuvos muzikos ir teatro akademija, 2020)—and particularly with the notion of “hauntology,” will be discussed later.

[6] Júlia Dantas de Miranda, “Relações entre a imagem e a música eletrônica: a visualidade do gênero synthwave” (Licenciatura thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, 2018), 19.

[7] Julia Neuman, “The Nostalgic Allure of ‘Synthwave’,” Observer, July 30, 2015; Andrei Sora, “Carpenter Brut and the Instrumental Synthwave Persona,” in On Popular Music and Its Unruly Entanglements, ed. Nick Braae and Kai Arne Hansen (Cham: Springer International Publishing, Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 143. Other than these two examples, virtually every account agrees with the “official” timeline.

[8] Miranda, “Relações,” 13–17, provides a systematization in which synthwave is seen as an evolution of the first “outrun” revival of 1980s electronica, explicitly drawing inspiration from cinematic sources. In websites devoted to the genre, such as Iron Skullet (site discontinued, available through Internet Archive here ), one can find a similar distinction where outrun music mixes elements from 1980s pop culture with house music and other kinds of contemporary electronic music.

[9] Philip Tagg, Music’s Meanings: A Modern Musicology for Non-Musos (New York: The Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, 2012), 522.

[10] See Jessica Blaise Ward, “Style and Digital Music Genres: Combining Music Style Parameters with the ‘Paramusical’” (BFE-RMA Research Students’ Conference 2020, The Open University, Milton Keynes, 2020); Arttu Kataja, “Elektroninen tanssimusiikki. Synthwave -singlen tuotanto” (Thesis, Tampereen ammattikorkeakoulu, 2017), 16.

[11] This is especially true when the presence of technological mediation is made apparent, if not overemphasized, as it happens in much “retro” music employing what Brøvig-Hanssen calls “opaque mediation” (as opposed to the “transparent mediation” sought by most popular music). See Ragnhild Brøvig-Hanssen, “Listening to or Through Technology: Opaque and Transparent Mediation,” in Critical Approaches to the Production of Music and Sound, eds. Samantha Bennett and Eliot Bates (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018), 195–210.

[12] See Silvia Segura García, “Nostalgia ON: Sounds Evoking the Zeitgeist of the Eighties,” Journal of Sound, Silence, Image and Technology 2 (2019): 24–43. More specifically on this topic, Segura García mentions Eirik Askerøi’s categorization of three kinds of “sonic markers of time,” retromaniacally referencing to past ages of popular music history: vocal peculiarities, (e.g. singing styles, like crooning), instrumental sound and style, and, most importantly, technological aspects of production. Eirik Askerøi, “Reading Pop Production: Sonic Markers and Musical Identity,” (PhD diss., Universitetet i Agder, 2013), 2.

[13] See Maurizio Corbella, “Suono elettroacustico e generi cinematografici: da cliché a elemento strutturale,” in Suono/immagine/genere, eds. Ilario Meandri and Andrea Valle (Torino: Kaplan, 2011), 29–48. As a matter of fact, the connection between electronic sounds and the (science-fictional) “other” can be traced back to the origins of both sound synthesis and cinema and is not limited to the common link with technology—see Maurizio Corbella and Anna Katharina Windisch, “Sound Synthesis, Representation and Narrative Cinema in the Transition to Sound (1926–1935),” Cinémas 24, no. 1 (2013): 59–81.

[14] This expression comes from Giorgio Moroder’s own words featured in the intro to Daft Punk’s song “Giorgio by Moroder.” Anecdotes aside, it is easy to see why the sound of the synthesizer could be perceived as something quintessentially new, artificial, mechanical, technological, and futuristic.

[15] See James Wierzbicki, “Weird Vibrations: How the Theremin Gave Musical Voice to Hollywood’s Extraterrestrial ‘Others,’” Journal of Popular Film and Television 30, no. 3 (2002): 125–35, for an account of the first associations between electronic music (and especially the theremin) and sci-fi. Lisa M. Schmidt, “A Popular Avant-Garde: The Paradoxical Tradition of Electronic and Atonal Sounds in Sci-Fi Music Scoring,” in Sounds of the Future: Essays on Music in Science Fiction Film, ed. Mathew J. Bartkowiak (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2010), 22–41, goes in the same direction when stating that “no matter how pleasing it may be to the ear, the electronic may always signify both itself and an anxiety about authenticity, and might have always been pre-destined to be alien” (36).

[16] See Timothy D. Taylor, Strange Sounds: Music, Technology and Culture (New York: Routledge, 2001), 93–94; Andrew May, The Science of Sci-fi Music (Cham: Springer, 2020), 12–14. Schmidt, “A Popular Avant-Garde” further examines the role of experimental sci-fi music as opposed to what followed. On Forbidden Planet, see Rebecca Leydon, “Forbidden Planet: Effects and Affects in the Electro Avant-garde,” in Off the Planet: Music, Sound and Science Fiction Cinema, ed. Philip Hayward (London: John Libbey, 2004), 61–76.

[17] See Michael Hannan and Melissa Carey, “Ambient Soundscapes in Blade Runner,” in Hayward, Off the Planet, 149–64. In 1982, Vangelis was also the first composer awarded with an Oscar for a completely synthesized soundtrack (Chariots of Fire).

[18] See Jeff Smith, “Bringing a Little Munich Disco to Babelsberg: Giorgio Moroder’s Score for Metropolis,” in Today’s Sounds for Yesterday’s Films: Making Music for Silent Cinema, ed. K. J. Donnelly and Ann-Kristin Wallengren (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 107–21.

[19] This is similar to another candidate for the position of influential synthwave movie from the same years: The Terminator (1984).

[20] Molly Lambert, “Stranger Things and How Tangerine Dream Soundtracked The ’80s,” MTV News, August 4, 2016, provides an overview of the soundtrack production by Tangerine Dream and of their relevance in the definition of contemporary synthwave clichés.

[21] Alexander C. Harden, “Kosmische Musik and Its Techno-Social Context,” IASPM@Journal 6, no. 2 (2016): 154–73; more on the genre in Alexander Simmeth, Krautrock transnational: Die Neuerfindung der Popmusik in der BRD, 1968–1978 (Bielefeld: transcript, 2016).

[22] Only one of Morricone’s compositions was used in the final version of the film, and Carpenter himself added some basic electronic background music to a few scenes. On the process of creating The Thing’s soundtrack, see Chris Evangelista, “John Carpenter’s Anthology: Movie Themes 1974–1998 Resurrects the Horror Master’s Classic Music,” /Film, October 19, 2017.

[23] According to Segura García, “Nostalgia ON,” 26, the second decade of our century corresponds to a typical “retro twin” revival cycle (in this case, of the 1980s) as theorized by Simon Reynolds in his influential volume Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past (New York: Faber and Faber, 2011), 408–9.

[24] Sora, “Carpenter Brut,” 143.

[25] Solaris, “Synthwave: Everything About This Genre Coming from the 2080s,” Synthspiria, September 27, 2018, (site discontinued, available through Internet Archive here). In the same article, Solaris describes a situation in which the underground and back then still unnamed synthwave reality (elsewhere apparently called “outrun,” thus referencing the arcade video game of the same name, featuring proto-synthwave music) gained its final form and recognition after the release of Drive. According to Franco Fabbri, “How Genres are Born, Change, Die: Conventions, Communities and Diachronic Processes,” in Critical Musicological Reflections: Essays in Honour of Derek B. Scott, ed. Stan Hawkins (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), 179–91, the act of naming a genre is crucial in the recognition of its birth.

[26] The importance of polygons or, more generally speaking, of the grid/matrix aesthetics, is emphasized by Kraujalis, “Synthwave Muzikos Stilius,” 13, and put into relation with the world of computers, futurism, and hyperreality. See Nintendo’s marketing campaign for the new Game Boy (Khepri Gaming, “Nintendo Game Boy TV Commercials, 1989–1993,” YouTube video, July 23, 2020) for a popular example.

[27] Sora, “Carpenter Brut,” 143–44.

[28] Solaris, “Synthwave.” Although, on the surface, the aesthetics can easily be juxtaposed, synthwave’s sibling genre vaporwave is characterized by precise configurations which only partially overlap with those described here; see Ross Cole, “Vaporwave Aesthetics,” for an introduction to this matter. For a more direct comparison, see Paul Ballam-Cross, “Reconstructed Nostalgia: Aesthetic Commonalities and Self-Soothing in Chillwave, Synthwave, and Vaporwave,” Journal of Popular Music Studies 33, no. 1 (2021): 70–93.

[29] See Kraujalis, “Synthwave Muzikos Stilius.”

[30] Mark Fisher, “What is Hauntology?,” Film Quarterly 66, no. 1 (2012), 16–24; Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (Winchester: Zero Books, 2014); Reynolds, Retromania, applies the concept to the musical realm more specifically. Fisher borrows the term from Jacques Derrida’s writings, where it is used with a quite different meaning; see Derrida, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International, trans. Peggy Kamuf (Abingdon: Routledge, 1994).

[31] Fisher, Ghosts of My Life, 22.

[32] Fisher, Ghosts of My Life, 113–14. The original quotation is from Fredric Jameson, “Postmodernism and Consumer Society,” in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Port Townsend: Bay Press, 1983), 117.

[33] For an introduction to retrofuturism, see Elizabeth E. Guffey, Retro: The Culture of Revival (London: Reaktion Books, 2006), 152–59.

[34] See Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1994). This concept has already been successfully applied to synthwave’s sibling-genre vaporwave in Gytis Dovydaitis, “Celebration of the Hyperreal Nostalgia: Categorization and Analysis of Visual Vaporwave Artefacts,” Art History & Criticism 17 (2021), 113–34.

[35] Miranda, “Relações,” features an entire gallery of original illustrations in “retrowave style” for each song off a Perturbator album, with explanations and descriptions that are useful to understand visual aesthetics of synthwave.

[36] See Benjamin Woo, Getting a Life: The Social Worlds of Geek Culture (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2018).

[37] Marcello Sorce Keller, “Piccola filosofia del revival,” in La musica folk. Storia, protagonisti e documenti del revival in Italia, ed. Goffredo Plastino (Milano: il Saggiatore, 2016), 59–106, emphasizes the role of revivals in the selection of specific traits of the original phenomenon following aesthetical, political, and ideological principles, thus partially betraying the very thing they are trying to revive. In the case of synthwave, it is quite clear that there is an idealization of the 1980s that gets mixed with clichés deriving from the representation by the media of that same age—again: a sort of hyperreal version of the 1980s. Synthwave also fits the notion of “vintage mood” elaborated by Daniela Panosetti, “Vintage mood. Esperienze mediali al passato,” in Passione vintage. Il gusto per il passato nei consumi, nei film e nelle serie televisive, ed. Daniela Panosetti and Maria Pia Pozzato (Roma: Carocci, 2013), 13–59. Panosetti describes the fascination with the past as a comfort zone which people can occasionally visit for a limited period to reuse or even transform single elements to transcend time.

[38] See Kayla McCarthy, “Remember Things: Consumerism, Nostalgia, and Geek Culture in Stranger Things,” The Journal of Popular Culture 52, no. 3 (2019): 663–77.

[39] See Jason Landrum, “Nostalgia, Fantasy, and Loss: Stranger Things and the Digital Gothic,” Intertexts 21, no. 1–2 (2017): 136–58. The series’ soundtrack is indeed rich with references to actual 1980s songs by artists like Kate Bush, Kiss, Metallica, Talking Heads, and The Police. As described by Segura García, “Nostalgia ON,” 27, several scholars and critics (for example, Simon Frith and Simon Reynolds) have long emphasized the power popular songs have in shaping collective memory and evoking the vibe and atmospheres of their time.

[40] See Sean O’Neal, “Stranger Things’ Score is a Gateway into Synthwave,” The A.V. Club, August 2, 2016.

[41] Music transcriptions by the author.

[42] For an introduction to every synthesizer used in the opening theme, see “Stranger Things Composers Break Down the Show’s Music | Vanity Fair,” YouTube video interview for Vanity Fair, uploaded June 15, 2018.

[43] See Landrum, “Nostalgia, Fantasy, and Loss.”

[44] As David Crow puts it, the 2014 movie is set in “John Carpenter’s backyard.” See Crow, “It Follows: A Homecoming for ’80s Horror,” Den of Geek, October 22, 2018.

[45] Joseph Barbera, “The Id Follows: It Follows (2014) and the Existential Crisis of Adolescent Sexuality,” The International Journal of Psychoanalysis 100, no. 2 (2019): 395.

[46] Charlie Lyne, “It Follows: ‘Love and Sex Are Ways We Can Push Death Away,’” The Guardian, February 21, 2015. For a more scholarly account, see Victor Samoylenko, “Defying STIgma in It Follows,” Monstrum 1, no. 1 (2018): 198–210, and David Church, “Queer Ethics, Urban Spaces, and the Horrors of Monogamy in It Follows,” Cinema Journal 57, no. 3 (2018): 3–28.

[47] On YouTube there are interesting edited clips in which shots from the two movies are compared: see, for example, Jose Ortuño, “It Follows vs Halloween,” YouTube video, uploaded on September 6, 2016; Alessio Marinacci, “Halloween/It Follows (atmosphere),” YouTube video, uploaded on February 12, 2017.

[48] In Segura García, “Nostalgia ON,” 34, the author draws a parallel with Philip Drake’s considerations on retro cinema, while also highlighting the relevance of mass media in the depiction of past eras, especially for the definition of codes that qualify as “metonymically able to represent an entire decade.” See Philip Drake, “‘Mortgaged to Music’: New Retro Movies in 1990s Hollywood Cinema,” in Memory and Popular Film, ed. Paul Grainge (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003), 183–201.

[49] Probably a reference to Carpenter’s Escape from New York (1981), set in that year and featuring the year itself in several (e.g., French, Italian, and Spanish) translations of the title.

[50] Sora, “Carpenter Brut,” 143.

[51] As stated in “Drive Director Nicolas Winding Refn Talks Turning Weaknesses into Strengths,” YouTube video-interview by Toby Amies for Nowness, uploaded on June 22, 2016.

[52] A similar grouping after one main topic (that of an orphaned, forsaken individual lost in the postmodern reality) is investigated by Mark Featherstone, “‘The Letting Go’: The Horror of Being Orphaned in Nicolas Winding Refn’s Cinema,” Journal for Cultural Research 21, no. 3 (2017): 268–85. I think such lens applies quite appropriately for the miniseries Too Old to Die Young, too.

[53] Once again sci-fi classics and remakes/sequels work behind the scenes of the prehistory of modern synthwave, since one of Martinez’s most notable works is the score for Solaris (2002), Soderbergh’s remake of the classic sci-fi film by Andrei Tarkovsky (1972). In this soundtrack there is surely a lot of electronic music, but still far from synthwave standards.

[54] The idea of “more 1980s than the 1980s” is inspired by another famous film from that same age, Videodrome (1983) by David Cronenberg, in which the TV world is described as more real than reality itself. The pseudo-quote paraphrases the original (and exquisitely Baudrillardian) sentence pronounced by Prof. Brian O’Blivion in one of the movie’s pivotal scenes: “television is reality, and reality is less than television.”