FORUM

Sound Theaters of the 21st Century: Material Functions and Voltaic Performativities

edited by Gail Priest

Sound Stage Screen, Vol. 1, Issue 2 (Fall 2021), pp. 125–194, ISSN 2784-8949. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. © 2021 Gail Priest. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54103/sss16639.

Madeleine Flynn, Georgina Darvidis, Erkki Veltheim, performance of Diaspora by Robin Fox (Chamber Made production, 2019) - Photo credit: Pia Johnson.

It could be argued that the practices discussed in this Forum under the suggested term “sound theater” could just as easily be called music theater. Whether a work is considered sound theater or music theater will of course depend on where you stand in the debate on sonic art as a form different to music. While there is a significant overlap, I also believe that the practice of sonic art revolves around sounding and listening as critical and reflexive activities, [1] whereas music is concerned with structural elements of harmony, melody and metric rhythm and the calibration of these within established, predominantly historical structures. [2] Put simply, it is the intention, both in terms of the sounding and listening, that differs between sonic art and music. The works that I am keen to explore here grow out of the culture and practice of sonic art, rather than that of music (or the culture of theater with its emphasis on performative gesture for that matter). If this work may be allowed an alternative categorization, I am proposing sound theater as an overarching notion—and electronic sound theater for works critically engaging technology, which is mainly the focus here.

In 2019, in what now seems like a mythical time of uninterrupted artistic activity and unfettered mobility, I had the good fortune to travel to several festivals, and also experienced a generous (by Sydney standards) selection of touring international artists. This exposed me to a range of works that started me thinking about how electronic sound was manifesting differently in the second and third decade of the twenty-first century. I also had the honor of being commissioned to make my own large-scale performance work that developed in a way unlike any I had made previously. [3] I was struck by how these performances, rooted in experimental electronic sound practices, are becoming more performative via their materials, and their digital-mechanical hybrid methods of activation. These activations provide the “sonoturgical” arcs that drive the theatricality, without additional or imposed performative constructs. The introduction to this Forum will survey some of these intriguing performances providing a context for the following invited contributions that explore a number of projects and practices in more depth.

Ironically, much of my current academic argument is against taxonomic mapping, so the purpose of grouping together the practices discussed here is not so much out of a desire to pin down and define, to corral these artists in a paddock of my own fencing. Rather, it is my intention here to explore a range of practices that engage sonic material performativities in a way that has an intriguing lineage and opens new possibilities for further exploration, particularly as mediating technologies become more mobile and malleable. However, the influence of avant-garde music performances—e.g., Fluxus events, or the music theater of Heiner Goebbels—will not be ignored, rather reconsidered through this focus on sounding, listening, and materials.

Attempting not to impose an externally manufactured category, the essays that comprise this Forum for the most part feature “accounts” in which the artists discuss their own practices. Their intentions and preoccupations, expressed in their own words, create resonances and dissonances that may reinforce or dispute the Forum’s themes. This focus on experience and practice enacts my commitment to what I have termed a “tomographic approach,” in which the embodied, embedded experience of a sonic art event, expressed through “slices” from the inside, informs and enriches the commentary. [4] In this I am influenced by the epistemological approach of situated and partial knowledges as proposed by Donna Haraway in which the embodied, sited, and experiential is transparently acknowledged in the discussion, rather than writing from a pretense of unlocatable objectivity. [5] This knowledge is inevitably incomplete and partial, which should not be seen as a problem rather an opening—an invitation—an opportunity for connection with other specific and partial knowledges. It is in this spirit of offering partial knowledges for connection with others that this Forum also has a distinctly Australian flavor.

Then and Now

My sound practice began in the early 2000s, when, in Sydney at least, what marked the live experimental audio scene was its indifference (often to the point of disdain) towards performativity. Populated by people using small electrical devices, mixing boards, and laptops, any gesture that shifted beyond a flick of a finger seemed quite extreme. I entered this culture after ten years in the contemporary performance scene that had been riding high on postmodern waves of parody and camp, with a preference for physical over textual forms. The fact that there was an audience for the quiet, contemplative, and visually minimal came as a shock and relief to me. It is in this respect that I refer not just to a practice of experimental electronic sonic art but to a culture as well. There were a handful of wildly and willfully performative artists, often in the noise genre growing out of post-punk and industrial scenes (see the description of Lucas Abela’s performance below), but still the performative language was predominantly drawn from the gestures of playing and an energetic summoning from the sound rather than an additional aesthetically calculated language.

As the next two decades of the century have come and gone, so too have the participants of this scene. Interestingly, this move towards material performativities appears within the practices of both the handful of remaining mature artists, and the next generation. Caleb Kelly, one of the key curators, event producers, and academic commentators within the early 2000s suggests that this shift is a response to “digital fatigue.” He explains that there is:

a longing, from the artists, for a physical connection with the materials of their work. In the 2000s, the prevalence of digital production technologies, especially within the digital studio, led to a schism between artists and their materials, one that has only been further widened through developments in the complexity of digital processes. … Thus, makers have become estranged from the means of their practices. [6]

Sound and materials—particularly in relation to gallery arts, but also associated live performances—is very clearly the area of expertise of Kelly. He founded the Sound and Materials research group at the University of New South Wales, now known as Sound, Energies and Environments. [7] For the purposes of this Forum I will differentiate my interests by focusing specifically on how the “material turn” within sonic art manifests firstly in audio performances—gigs and concerts—and secondly, how some of these presentations are moving decidedly into the theatrical context, challenging what constitutes “performance” in this milieu.

Sonic Actions

Peter Blamey is a leading Australian artist, active since the 1990s. While the presence of performative materials has become more explicit over the years, it is not so much a change in modus operandi but the result of the development and refinement of conceptual preoccupations and creative motivations. Blamey began his engagement with music in the 1980s and 1990s as a drummer in bands. The shift towards sound happened through a keen interest in guitar and microphone feedback. [8] Since then Blamey’s work has maintained a focus on flows of energies manifested as sound. There is a certain respect and agency given to these energies so that he does not tame them, rather he creates conditions and situations that encourage them into existence and transformation. This is evident in his early 2000s experiments with mixing-desk feedback, a minimalist process with the potential of maximal sound, in which a mixing desk’s various outputs are fed back into its inputs creating its own feedback loop, modulated through adjustments of volumes and frequencies. Developing from this are his explorations in what he calls “open electronics,” feedback systems using discarded motherboards. These manifest as both installations as well as a performance series titled Forage. Blamey places clouds of copper wire onto an assortment of scavenged motherboards connected to small battery-powered amplifiers, gently nudging them into different configurations, the interaction resulting in fields of fascinating hum and buzz. Blamey describes these works:

The title relates both to foraging in streets and laneways for the computer components used, and to the way in which the performances involve a “foraging” for the signals coursing chaotically through this lively but unstable electrical environment. [9]

Blamey’s work actively engages in reuse and recycling as a critique of capital-driven technological obsolescence. His use of photovoltaic (solar) panels in systems of contingent energy scavenging also attests to his environmental concerns. It is the gestures involved in activating these materials in ways that manifest sound that make Blamey’s work uniquely performative. In his Invisible Residue performances, Blamey sonifies (via solar panels) the infrared signal of remote controls from long discarded equipment, performing with the signature sounds that each creates. [10] Along with the engaging and strangely rhythmic sounds, the all-too-familiar gesture of pointing the remote control creates a curious choreography that encourages critical reflection on this action, and its reinforcement of sedentary leisure, particular to the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Peter Blamey, Double Partial Eclipse, MCA Art Bar (2014) - Photo credit: Jenn Brewer.

Double Partial Eclipse (2014) involves two small photovoltaic panels that Blamey holds in varying proximities to a lightbulb, the resulting current running to ebows placed on an electric guitar. [11] Blamey “plays” the guitar by modulating the flow of energy to the ebow via distance and angle. Blamey’s measured and sustained gesture creates a mesmerizing performativity, as he seemingly plays the light and air. [12] In a recent performance configuration, Rare Earth Orbits, he uses spinning rare earth magnets and their closeness to electromagnetic coils to create a basic oscillating voltage, which is then amplified. [13] To generate the spinning he uses a hand clamp, a fishing reel, and a foot-pump activated air vent. The differently scaled actions are focused and minimal in range, with the intensity required to generate what he calls “‘handmade’ electrical activity” undeniably rigorous and full of intent that renders them highly performative. [14]

However, Blamey’s intention is not to invent innovative performance modes but to find ways in which the processes or flows of relations between materials and sounds can become evident to an audience. He tries to create situations in which sonic transductions and amplifications of materials reveal the interactions of their energetic flows. Blamey’s focus on obsolete, discarded technology not only engages with the immediate materiality of these objects, but also with “broader ideas relating to electricity, the history of technological artefacts, ecology and experimental practices in the arts.” [15] This affirms Kelly’s belief that a focus on materials allows for an expansion out from simply the phenomenal experience of sound to allow for more contextual critique. [16]

As a contrasting example, for the last decade or so Lucas Abela (Australia) has played amplified shards of glass. Pressing his mouth to the glass he blows, slurps, and sings, with changes in the “embrasure,” in combination with effects pedals, creating dynamic noise assaults. Inevitably the glass breaks, and Abela is not afraid to slice his face and lips as he continues. [17] This is undoubtedly a dramatic performance, but one I would argue still comes from an integrated engagement with materials and their sound potentials and the inherent performativity involved in exploring this.

Kate Carr at Les Instants Chavirés (Paris, October 2019) - Photo credit: David Lantran.

Elements of material performativity are also finding their way into many artists’ practices who were previously more laptop-based. Australian artist now based in the UK, Kate Carr’s foundational work is in field recording and minimal sampled instruments. Recently she has been integrating “a scientific rocker, a spinning beaker, wind up birds and suspended tape loops.” [18] Working through these material processes, she says, offers a “transparent liveness” explaining that “the risk of failure and malfunction they incorporate and the capacity to physically improvise with things ‘at hand’” offer her a spontaneity that she found lacking when only using a laptop and controller. The integration of these live elements is not new and remarkable in itself—this is what instruments offer—but it is the manner in which the exploration of the sonic potentials within materials are defining the scope and gesture—and are being allowed their own performativity—that is an interesting development within the experimental audio scene.

I doubt that any of these artists would consider their practices within the conceptual framework of sound theater; however, aspects of their work illustrate the integrated relationship of material and its activation that results in a sounding performativity. It is when this same approach to performative materials is scaled up within theatrical contexts that I believe we approach a mode of sound theater that has different motivations and asks for different listening intentions than music theater, with its origins in notated scores and (often but not always) narrative constructions. Sound theaters, I propose, are developing from the culture and practice of experimental audio in which the performance gestures and modes required to activate the sounding potential of materials, both acoustically and via technological manipulations, are inextricably entwined, providing the structure of the composition and the performance—of the performative composition.

Sonic Theaters

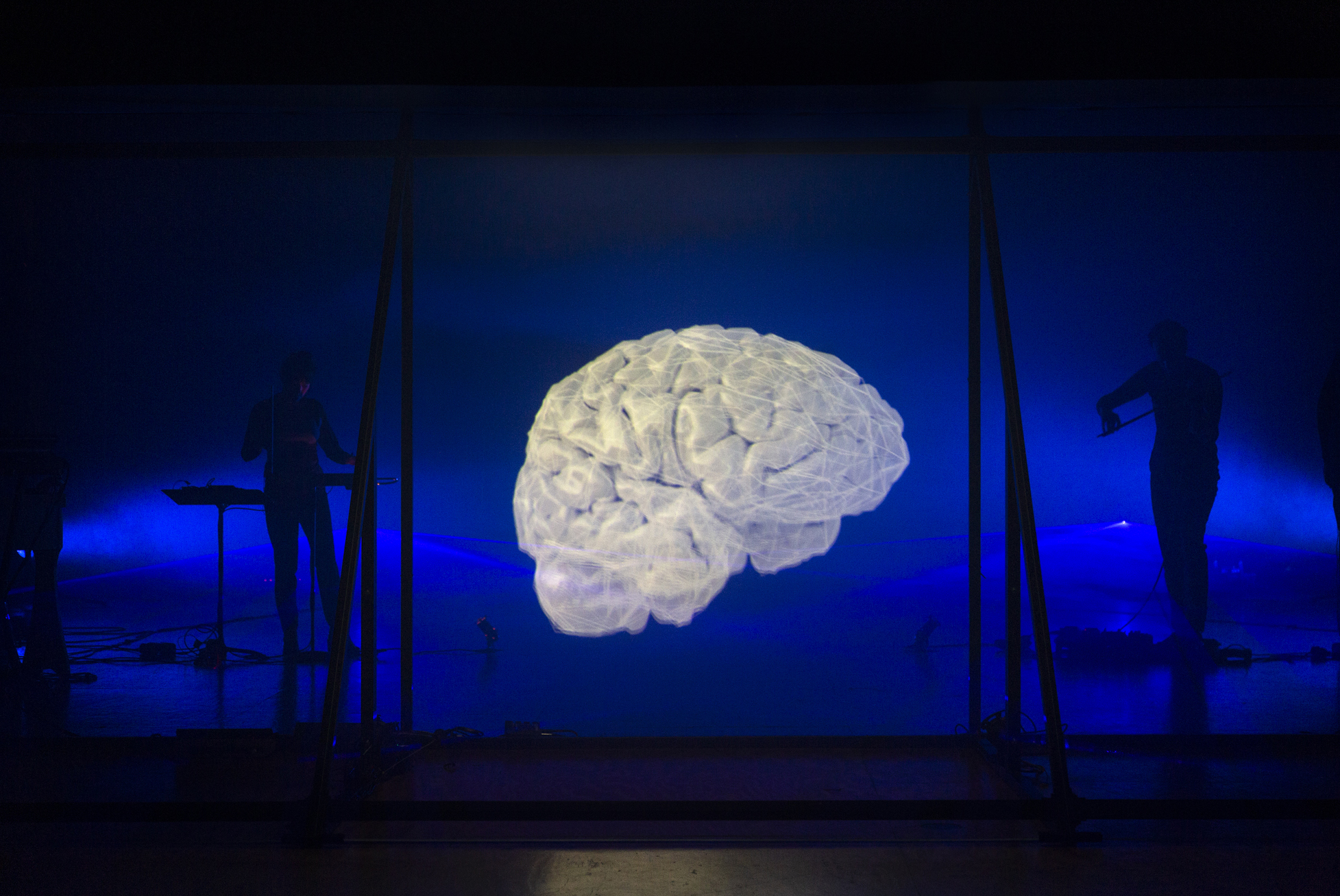

The seeds of this Forum were planted when I saw Diaspora (2019), created by Robin Fox with co-collaborators Erkki Veltheim and Tamara Saulwick, a “science fiction revelation” based on the first chapter of Greg Egan’s book of the same name. [19] Fox is internationally renowned for his audiovisual work using lasers. These concert pieces are undeniably theatrical, but Diaspora marks a significant framing shift to the constructs of theater, working with an overarching (albeit non-textual) narrative. However, the work maintains the conceptual ethos of electronic noise music, and the performative structure and arc of the work are driven by Fox’s synesthetic audiovisuality. In Diaspora, the performative material is voltage itself. An essay featuring interviews with Fox and dramaturg/performance-maker Saulwick, exploring the motivations and making of Diaspora, opens our selection of essays.

Another significant Australian work premiering in 2019 was Speechless, a “wordless, animated notation opera” by Cat Hope. [20] Hope’s artistic preoccupations revolve around bass frequencies, noise, and graphic notation. In Speechless she uses theForgotten Children: National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention report from the Australian Human Rights Commission (2014) as the unspoken “libretto.” [21] As well as informing the overall themes and message of the work, Hope used the material elements of the report—colors, infographics, and children’s illustrations—as inspiration for the graphic score that is presented in the Decibel ScorePlayer App. [22] The work is scored for an orchestra comprising only bass instruments, and four female vocalists from vastly different genres ranging from death metal to opera, who perform the textless piece. In the second essay of this Forum, Hope describes the intentions and processes of creating this remarkable work, which she herself describes as an opera but may also be productively discussed through the figure of sound theater. Hope’s work, while fitting comfortably within the “new music” classification, also embodies an ethos born of noise, pushing way beyond the sonorities and the notation of most contemporary classical music. The expanded sound world released through the scored translation of the materials of this devastating report actively mobilize the greater cultural, contextual, and political resonances, aligning this project with the critical reflexivities of sonic art.

Although it certainly could be argued that Speak Percussion, under the artistic direction of Eugene Ughetti, come from a contemporary classical music lineage, rendering them well-suited to the term music theater, I would argue that their commitment to explorations of sonority, integration of technology, and adventurous collaborations exemplifies electronic sound theater. Ambitious works such as Transducer (2013), co-composed by Ughetti and Robin Fox, focusing on the materialities of the microphone and speaker; [23] or Polar Force (2018), a collaboration with renowned sound artist/field recordist Philip Samartzis, exploring the sonic potentials of ice, [24] are examples of the kind of material performativities that create sound theater. Also notable are the solo works of Matthias Schack-Arnott (a former artistic associate of Speak Percussion), such as Anicca (2016) and Everywhen (2019), that are based on the interaction of the performer and complex kinetic mechanisms. [25] This results in hybrid, embodied event structures in which the action, materials, and soundings are fully integrated.

Eugene Ughetti and Matthias Schack-Arnott during a performance of Polar Force (Speak Percussion, 2018) - Photo credit: Bryony Jackson.

While I have been concentrating on Australian works, this tendency to explore sound theaters is evident internationally, particularly at Sonica, a biennial festival presented by Cryptic in Glasgow (UK). A highlight of the 2019 edition was SpaceTime Helix (2012) by Italian artist Michela Pelusio. [26] Pelusio’s “optoacoustic instrument” is a single cable, attached at floor and ceiling, activated to create a spinning standing wave, which with the help of strobe lighting creates a dynamically changing helix. The acoustic sounds of the mechanism, and its electromagnetic signals, are processed to create the tensile escalating soundscape drawn directly from this awe-inspiring demonstration of split, bent, and blended light. Another highlight, offering a completely different aesthetic, was Argentinian artist Nicolás Varchausky’s Mesa de Dinero/Money Desk (2018). [27] Using modified money counters and scanners, he amplifies the actions of counting his artist fee. Working with both the aesthetics of the sound of the machines and the functional clarity of the task-based actions, Varchausky sonifies the materiality of money, and the immateriality of the global currency markets in a way that allows the materials to “become” both performers and activists, again exemplifying Kelly’s notion of the political potential of material sound.

Kathy Hinde is a Cryptic Artist, presenting many major works within multiple Sonica festivals. In 2015 I experienced Tipping Point (2014), a breathtaking installation that can also be played live, a hybrid format that allows materials to express themselves independently and become performative instruments. [28] In the third essay Hinde talks with Matthew Sergeant about her worksPiano Migrations (2010), Tipping Point and Twittering Machines (2019), that exemplify the way in which she approaches the manipulation of materials so as to engage with their non-anthropogenic contingencies. In this Hinde critically connects our material discussions with current theories of object-oriented ontologies and agential realism.

Theatrical Soundings

Branch Nebula (led by co-artistic directors Lee Wilson and Mirabelle Wouters, with visual artist Mickie Quick and sound designer Phil Downing as frequent collaborators) presents physical theater works that openly exploit the material performativity of sound. In Wilson’s virtuosic solo performance piece High Performance Packing Tape (2018), real-time audio processing sonically elevates the humble materials of office stationery misused as circus apparatus. [29] In Crush (2020), the sonic integration intensifies with several sections driven by audio activations. An enormous sculptural lattice of PVC piping turns into a ructious aeolian organ with the assistance of an industrial vacuum cleaner. A searing dronescape is created when the performers attempt to drag heavy guitar amps by amplified wires, the physical and sonic tension responding in direct relation. Branch Nebula allows the theatrically sonic to be an integral structural and dramaturgical element of their work, thus rendering their practice truly interdisciplinary.

Mirabelle Wouters during a performance of Crush (Branch Nebula, Sydney Opera House, 2020) - Photo credit: Prudence Upton.

It is in this context of theater—one which pays exceptional attention to the integration of sound’s own theatricality—that this Forum features an essay by composer/sound designer Scott Gibbons, a regular collaborator of Italian theater director Romeo Castellucci and his company Societas. He shares his process notes and musings on developing the sound world for the company’s recent project, BUSTER. We are privileged to learn of Gibbons’s material experimentations and manipulations as well as some new strategies required for collaborating remotely in global pandemic conditions.

Sonic Thingness

I can date the initiating spark behind this Forum further back to 1998, when I had the pleasure of seeing Heiner Goebbels’s Black on White (originally created in 1996 as Schwarz auf Weiss) at the Adelaide Festival. I recall the moment when a musician from the Ensemble Modern put on a kettle to make a cup of tea. As they waited, they ignited a tea bag, its flaming convection sending it aloft. This magical flight was accompanied by the kettle’s whistle; Goebbels says this is “a C major triad, which first the flute player and finally the whole orchestra play along with.” [30] By inserting this simple domestic action (among many others) into the orchestral context, Goebbels intended “to create an un-hierarchical balance in the world of sounds.” [31] However, in the process of introducing the sounding functions of objects, he realized that they, in fact, began to exert power over the musicians. Discussing the presence of these material situations in his early works, he says:

the presence of things might not yet act as a major character of the works in total, but the things rather show up, they capture the space, they conquer more and more the performances and the compositions, they choreograph the words, the movements and actions. The more they insist on their being, the more they call for respect, for their own timing. [32]

In Stifters Dinge (2007) Goebbels finally allows the objects full reign with the piece featuring no (visible) human agents, only five pianos, mechanical devices, as well as recreated elements such as rain, fog, and ice. Goebbels describes the effect of the integration of sounding “things” on an audience:

It demonstrates a different way of experiencing, or even confronting, the way we perceive the sounds of things on a day to day basis. It gives us a bigger freedom for our imagination and also it avoids this enormous reflex we have to upload things with an anthropomorphic center. Those sounds also avoid the reflex to mirror ourselves, to identify ourselves with what we see and hear. Sounds of the things do not allow an easy identification. And that is what I basically try to work on: not to work on a direct encounter with somebody we can recognize, but rather on an indirect encounter with alterity. [33]

In a 2011 lecture Goebbels also references this alterity suggesting that his use of objects and processes has the intention to destabilize the audience’s sense of self-identity, offering an “insecure confrontation with a mediated third … the other.” [34] Once again, we see how an engagement with the material soundings as performative events can lead to contemplations of political and philosophical context, beyond the sensorial pleasures of sonority. While Goebbels’s reputation as the master of “music theater” may seem to undermine my argument for sound theater as something apart, [35] I would propose that considering the work of Goebbels through the proposed premise of a sound theater that focuses on material behaviors and their sonic consequences allows for an enhanced appreciation of his practice.

Sonic Flux

The focus on materials, objects, and their activation as functions and tasks also brings Fluxus events (influenced by avant-garde Cagean practices) into focus. Douglas Kahn describes the shift in the way sound is considered in Fluxus:

The historically earlier question of What sounds? receded in Fluxus and was replaced with questions such as Whether sounds? or Where are sounds in time and space, in relation to the objects and actions that produce them? [36]

Kahn highlights the “incidentalness” in the way in which sounds were, or in fact were not generated. In something like George Brecht's’ Incidental Music (1961), fulfilling the task takes precedence over generating a sound. [37] Similarly in Shiomi Mieko’s Boundary Music (1963), the artist calls for the action of making “the faintest possible sound to a boundary condition whether the sound is given birth to as a sound or not.” [38] However, ultimately Kahn is critical of how sounds are still musicalized within the Fluxus mode:

From the standpoint of an artistic practice of sound, in which all the material attributes of a sound, including the materiality of its signification, are taken into account, musicalization is a reductive operation, a limited response to the potential of the material. [39]

Here Kahn provides us with the language with which to argue for a sound theater practice. The practices of material sound performance explored above are not simply musicalizing the sonic consequences of material interactions but are attempting to engage more fully with the cultural contexts this material sounding implies and activates.

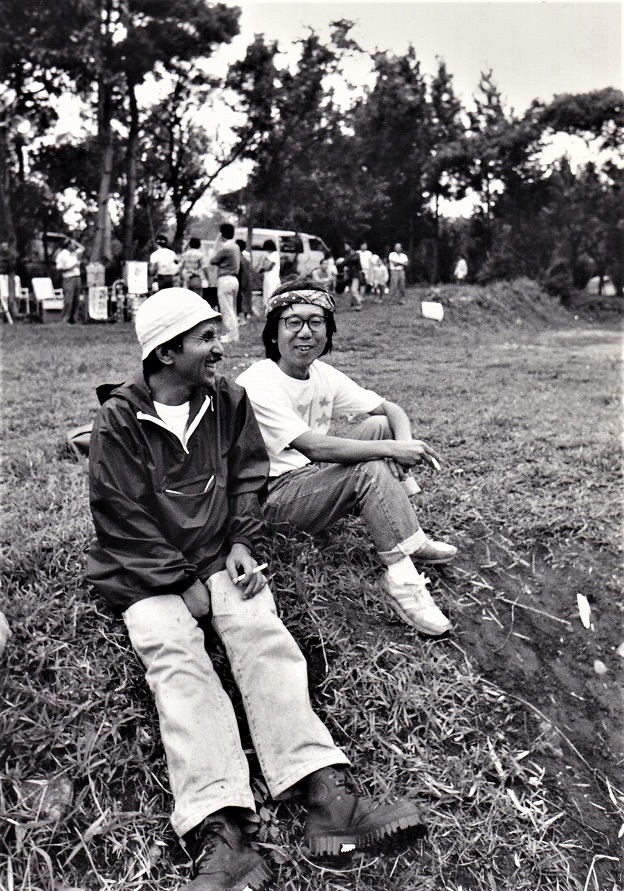

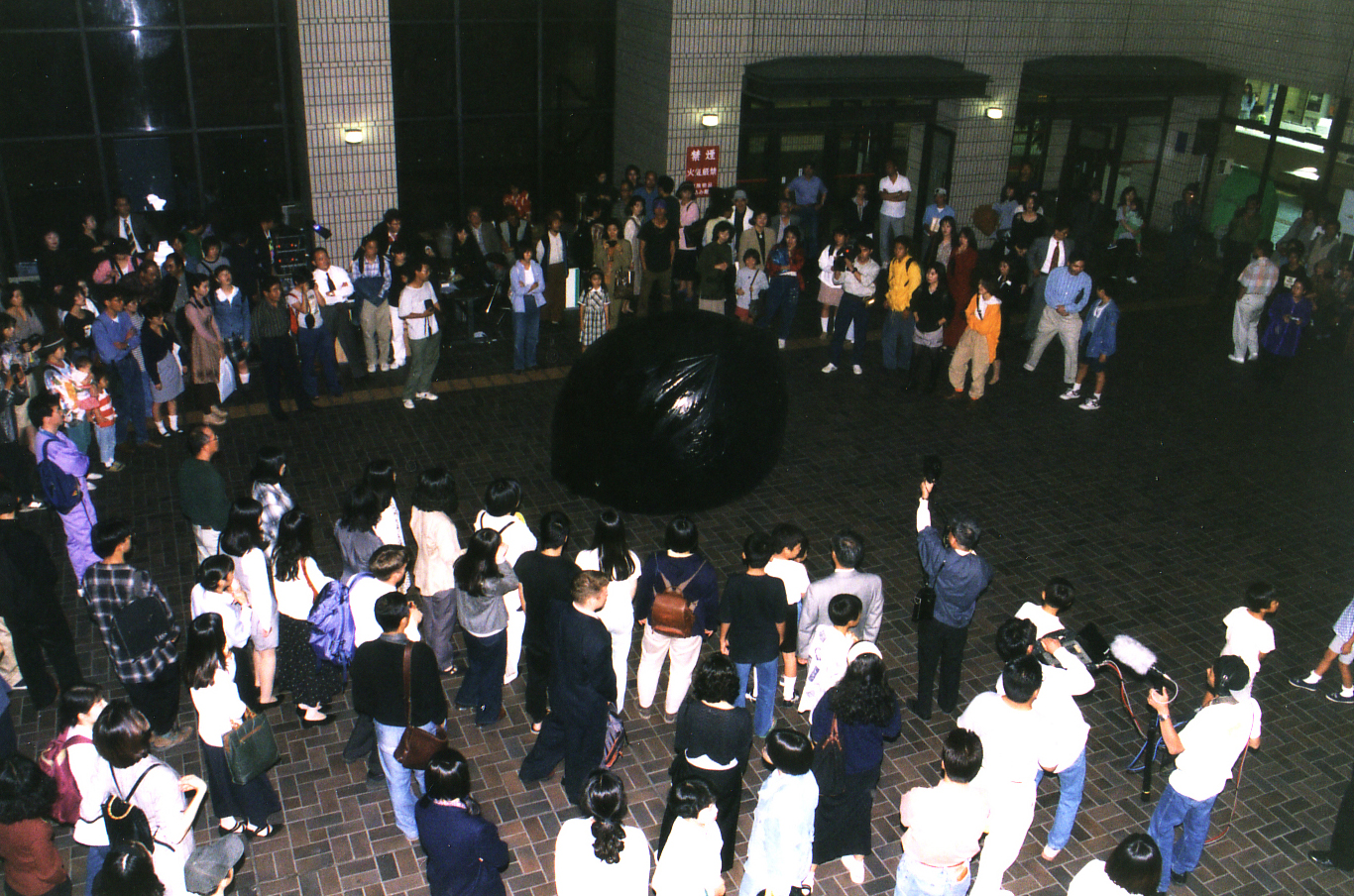

The engagement in the event of material sounding was not confined purely to American and European explorations, as evidenced by Japanese artist Shiomi’s text score cited above. For this Forum, it is through the collaborative work of artist-composer Kosugi Takehisa and performer Kazakura Shō that this era and aspects of performative sound materials will be further explored. Christophe Charles, a Japanese-based artist and academic, had the privilege of working with Kazakura. His detailed historical research includes excerpts from a personal interview with Kosugi and original translations that allow the artists’ significant presences to be felt. What is revealed is a fascinating approach that focuses on how these artists—one from music, one from theater—created a collaborative practice through a shared engagement with the materiality of space, time, and the unseen/unheard flows of energies. The influence of artists such as Kosugi and Kazakura can be experienced in the performative material soundings of contemporary Japanese artists, such as ASUNA and his mesmeric durational drone piece 100 Keyboards (2014), [40] and the sublime sonic kinetic scrapyard of Umeda Tetsuya’s Things That Don’t Know/Ringo (2017), [41] which also initiated my thinking around material sound performativities and sound theaters. [42]

Sound-/Music Theaters — Together Apart

Aspects of avant-garde music, Fluxus, and music theater works (such as those by Heiner Goebbels) all potentially exert a “musical” influence on the projects discussed here. However, I also hope to have revealed how these projects engage a performativity that moves beyond and away from the structures of music to that of material sounding. A key part of this is an emphasis on sonorities that arise from gesture as functional task creating an integrated performance-sound structure. Also pertinent is an intention to create contexts in which listening engages with both the phenomenal sound, but also opens up historical, political, and contextual understandings. I am the first to admit that I have not made a watertight defense. However, what I hope I have done, in both this introduction and the selection of invited essays, is to present a number of connected perspectives, drawn from experience, that allow for a productive consideration of the practice of sound theaters. Inevitably, just as no one has yet managed to clearly extract sonic art from music, sound theater also cannot, nor should be, completely extracted. Rather, the two might be considered through Karen Barad’s proposal of a cut or separation that is, within one move, both “together-apart,” a proposal, based on quantum field theory, that defies binaries and allows for people, thoughts, situations, and things to contain itself and other as separate continuities. [43] I leave you to consider the possibility of “sound-/music theaters,” existing, both together and apart, with the specificities to be considered contingently, intentionally, and contextually.

Gail Priest

Sounding Digital Consciousness: Robin Fox & Chamber Made’s Diaspora

Robin Fox and Tamara Saulwick interviewed by Gail Priest

Diaspora Trailer (2019) from Chamber Made on Vimeo.

Robin Fox’s Diaspora (2019) is a hybrid audiovisual event shaped by a “narrative” of sorts that transforms the live electronic music gig or concert format into that of a theatrical experience in a way that might be described as electronic sound theater. [44] In the following essay, fragments from interviews conducted with the project’s lead creator Robin Fox, and co-director/dramaturg Tamara Saulwick, are presented as input and stimuli, in an attempt to grow and develop this notion, or this consciousness, of electronic sound theater, in a manner that is not dissimilar to the coming to consciousness of the entity that is the protagonist in this impressive work.

Georgina Darvidis, performance of Diaspora by Robin Fox (Chamber Made production, 2019) - Photo credit: Pia Johnson.

Origin Stories

It was while experiencing a performance of Diaspora in 2019 that I began to develop this impression that there is an evolving practice of electronic sound theater that might be productively considered as not entirely the same as music theater. As discussed in the Forum introduction, the theatrical outcome of these works is surprising due to the composer-creators’ practices focusing on digital, and frequently non-gestural forms of experimental electronic music and sound art. Fox’s background incorporates both composition (he has a PhD from Monash University) and he has worked as a composer and sound designer for dance; however, considering the nature of his practice, which is intensively electronic, noise-based, and non-figurative, the move to instigating his own complete theater work might seem surprising.

Since the late 1990s, Fox worked extensively on laptop to create live processing systems, including a well-renowned collaboration with Anthony Pateras. He made a significant move towards the visual in the early 2000s via experiments with a cathode-ray oscilloscope, [45] feeding it sculpted noise and projecting the corresponding patterns via live video. This developed into his experiments with lasers. Using a similar process of translating audio voltage to visualized oscillation (and sometimes vice versa), Fox projects the lasers outwards into a smoke-filled auditorium, carving the space into three-dimensional geometric landscapes of tone and noise, in which both sound and image are manifestations of what Fox describes as shared voltage. These projects have become increasingly ambitious, starting with a basic green laser and then moving to the colorful spectacle of RGB. Fox produces works for both standard concert formats and large-scale site-specific performances, such as Aqua Luma (2021), taking place in the Cataract Gorge in Launceston, Tasmania; or Sun Super Night Sky (2020), a laser installation with streamable soundtrack for the Brisbane city skyline.

While Fox’s audiovisual works are presented in electronic music and sound art festivals, he has also worked in theater, particularly as a composer, sound, and lighting designer for contemporary dance works. Very early on in his career he was involved with Chamber Made, then known as Chamber Made Opera.

Fox: The first large work that I made when I was still at university, studying composition, was with Chamber Made. It was a bizarre revisioning of the Narcissus and Echo myth that I wrote for four turntables, double basses, and operatic voices… [Mauricio] Kagel’s Staatstheater really had a big impact on me when I was a student and so these early pieces of mine were very much of that nature. They were based in sound and rooted in sound, but the intent was operatic and theatrical in a kind of oblique way. [46]

When Fox was approached by violinist-composer Erkki Veltheim (then an Associate Artist at Chamber Made) to create a work, he decided to attempt a science fiction opera based on the first chapter of Greg Egan’s novel Diaspora.

Fox: One thing that I’d often joked about with opera is: “Why haven’t we ever had a science fiction opera?” … Once it occurred to me that I wanted to make a science fiction opera, I knew exactly what I wanted it to be—a rendering of the first chapter of Diaspora. … I just loved the description [it gives] of the birth of a digital consciousness—which I had to go to great pains to distinguish from an artificial intelligence. It has this incredible, quasi-mathematical computer “programmery” but also very DNA-driven description of the birth of this life form … It is incredibly evocative and incredibly musical, actually. … [It] suggested all kinds of musicality.

Tamara Saulwick, the co-director, dramaturg, and current artistic director of Chamber Made, makes performance works that are inextricably entwined with sound and sound technologies.

Saulwick:

I came into sound surreptitiously. I was working just with recorded voices

… documentary materials or first-hand accounts … So first of all, they

became useful in terms of constructing content; then, I became increasingly

interested in the materiality of sound, the quality of those recorded

things, and the detritus within the recordings—and that became part of the

language of the work.

I was working on some solo material, and I’d become very interested in this

intersection between live and pre-recorded—video and audio, actually. I was

really interested in this slippage between the mediated and the live body

and voice. Working between recording and liveness is a really fertile space

that continues to fascinate me. … I’ve [also] been living with a musician

[Peter Knight, currently Artistic Director of the Australian Art Orchestra]

for the last twenty years—surrounded by a lot of music, sounds, doing a lot

of listening and a lot of talking [about sound].

[47]

Saulwick and Knight have collaborated on several of her solo performance projects, including Pin Drop (2010–14), which uses recorded interviews and foley techniques to explore the role of listening within fear; [48] and Endings (2015–18), with songwriter Paddy Mann, using mobile record players and reel-to-reel devices to create the sound character of the work. [49] Given Fox’s established audiovisual language, Saulwick saw that her role in Diaspora “was to facilitate the work coming into being … trying to support Robin, but also the whole group to make [the work] the most ‘itself.’”

It is also interesting to note the origins and progression of the company Chamber Made. It was formed in 1988 by stage director Douglas Horton to create original chamber opera works. Composer David Young became artistic director in 2009, and grew the reputation of the company by creating intriguing, opera-in-miniature works, often in private houses, site-specific locations, and expanding into new media and digital realms. Tim Stitz took over in 2013 and moved the company to a model that drew on creative input from associate artists, of which Saulwick was one. Saulwick moved into the artistic director role in 2018. In 2017, the “Opera” part of the title was retired to reflect the contemporary focus on interdisciplinary works that explore the relationship between performance, sound, and music.

Composing Consciousness

Georgina Darvidis, Erkki Veltheim, performance of Diaspora by Robin Fox (Chamber Made production, 2019) – Photo credit: Pia Johnson.

The sound, structure, and scenography of Diaspora comes from the audiovisual compositional interpretation of the birth of the digital consciousness as described in Egan’s text, but with no narrative-based dialogue. (Several of the pieces involve lyrics but these texts operate as part of the sonic fabric rather than as narration.) Saulwick describes the compositional process:

Saulwick: Erkki and Robin quite literally translated what they saw as this kind of arc of development within the writing. They had musical motifs that had direct correlations to ideas in the text, and it was done in a series of parts. One of the reasons why I think Robin always thought that it would be a good source, is that in many ways the language translates very readily to a compositional format, because [it] talks about building layers and complications of theme.

Fox explains the choice of instruments and palette of the composition:

Fox: I’m fixated with modular synthesizers, so I wanted to make [them] a big [feature of the composition]. [50] I also wanted to use the electronic instruments as props so that the machines are part of the ethos of the work. But I also really wanted to work with musicians … Electronic instruments lend themselves to this kind of automated delivery rather than human gestural delivery. I’ve always had [an] issue with electronic instruments not vibrating. You don’t have the appropriate proprioceptive feedback from a vibrating body. It’s really the sound system that’s your instrument in that sense. It’s not the computer or the software, it’s the speaker that’s the vibrating thing in the room. Working with Erkki, I was going to be working with violin, so I liked the juxtaposition of that. Working with modular synths [but] then also with the most iconic, conservative, orchestral instrument family. The violin is such an iconic reference point for all kinds of music; it encapsulates that high/low culture that we really exploited in the work as well. […]

Robin Fox, Madeleine Flynn, Erkki Veltheim, Georgina Darvidis, performance of Diaspora by Robin Fox (Chamber Made production, 2019) - Photo credit: Pia Johnson.

I wanted to work with great musicians. Madeleine Flynn is a great musician

[pianist] and so the ondes Martenot made really good sense there as an

electronic instrument that embodied that theremin like quality.

[51]

Then the idea of having a voice [Georgie Darvidis] … a human voice that

would sit alongside the very inhuman construct of a lot of the other

aspects of the work. … It did come from this electronic premise, but there

was so much of it that wasn’t electronic by design … I wanted performers to

be on stage … I didn’t want to do a sound design that supported the

theatrical action or even a sound design that supported a sort of visual

installation. Tamara and I would often have these dramaturgical

conversations where my position would be: “this is a gig”—a gig in this

kind of bizarre set. …

There were set pieces, but there was a lot of flexibility in the way [ Diaspora] was played. I wanted to keep that musicality about the

work. I think that’s part of my problem with some of these other things

that I work on, in contemporary dance, where you have to nail everything

down. I deliver the soundtrack in this electronic form, design a sound

system and then it’s cued the same way every night. It’s a show and that’s

a great way to work, but it’s also not very musical. So I did very much

have in my mind that idea of this music-driven theater; the music, and the

way we composed the music, was really at the core of each section of the

work. …

Even though it did have theatrical or narrative qualities at times, all of

the ideas came from the sound and the generation of the sound, and what we

were trying to do with the music, not just sonically, but linguistically …

to me music is incredibly linguistic … [I mean in] that kind of punch card

way that notation has of turning [sound] into a sentence structure and a

grammatical structure. You have a form so that then, in the same way you

would construct a sentence, you construct a phrase, and then you construct

a paragraph. I’m always interested in the intersection points between that

kind of linguistic approach to music and then sound as another thing which

doesn’t have that linguistic intent.

Georgina Darvidis, Erkki Veltheim, performance of Diaspora by Robin Fox (Chamber Made production, 2019) - Photo credit: Pia Johnson.

A key instance within the performance that plays with this musical linguistics is the section that sounds like an interbreeding of a Bach partita and Country and Western hoedown featuring virtuosic performances by Veltheim, Darvidis, and Flynn. For Fox and Veltheim, this piece of very strange composition exemplifies the issue that arises around the cultural context of data that is too easily lost in machine learning:

Fox: The idea behind that was trying to make music that an artificial intelligence (even though we weren’t looking at AI particularly) might make. What would an artificial intelligence make if it could make music and why? And because artificial intelligence is algorithm-based, based on data input it seemed logical that it would analyze a Bach violin partita and then analyze a hoedown and realize that structurally they were almost identical, then just put those two things together, because it doesn’t have any cultural baggage. It doesn’t realize that they actually represent two very different paradigms in terms of music and how we appreciate it as human beings, and in our human cultures. So, I like the idea that in a science fiction world there is no delineation between those … those forms. [52]

In another section, Darvidis sings a version of “Somewhere over the Rainbow” that is digitally diced, spliced, and fragmented almost beyond recognition, yet—for a human audience that understands cultural contexts—resonates with the bittersweet longing to be elsewhere and other. These unfamiliar familiarities are even more curious as they emerge from an extended meditative opening sequence (sustained for over twenty minutes) of undulating sine tones and sub frequencies that—along with the accompanying laser light translations carving the smoke-filled air—render the space thick with affective vibration. Fox talks about wanting to play with the balance of these linguistically music and abstract sonic elements:

Fox: It’s very difficult to present something that’s non-linguistic sonically and have it appreciated without a linguistic lens. I think people still want music and resolution; you know, tonic to dominant resolution—the psychoanalytic safety of all of those structures. … So, I think with this work there are sections where I just wanted it to sit for a while in places that were very strange and not be concerned about where they were going.

For me, this extended opening illustrates how this performance operates on a sonic art sense of time, one that allows for a more ambient and patient extrapolation, rather than musical and theatrical time that often progresses through the accumulation of actions and established moments. I asked Saulwick how she worked with these different time structures:

Saulwick: I think of [Diaspora] as an expanded concert. The opening sequence was a long sustain. I felt like my job was going “Okay, how can we shape the unfolding of visuals—stage lighting and video materials—to meet that tempo?” In terms of the audience experience, it was very physical, like you were in a big bath of sound … [with the] massive subs under the seating, the sine tones were kind of actually waving through you physically. I think that places people in time in a different way. They can really settle into it.

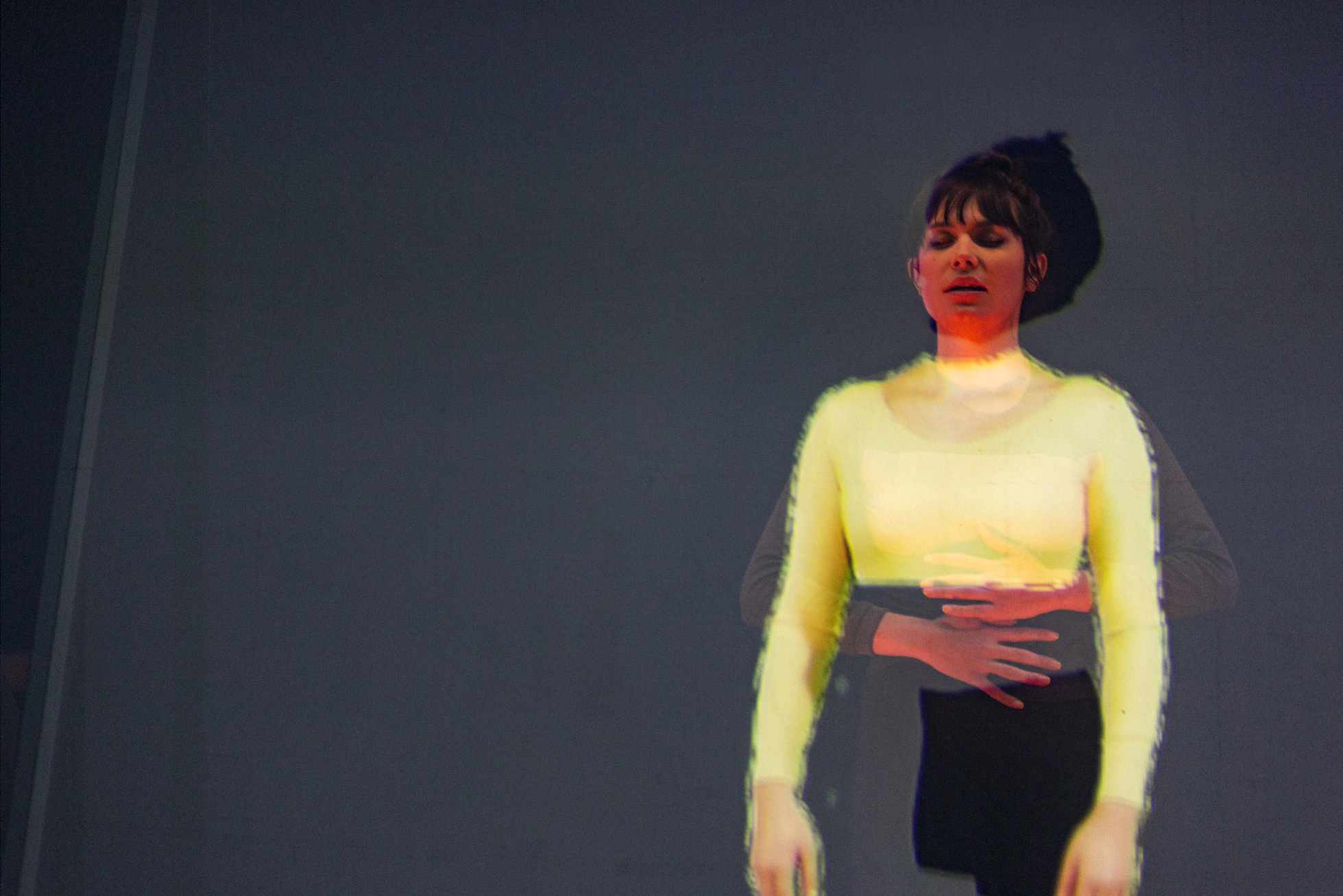

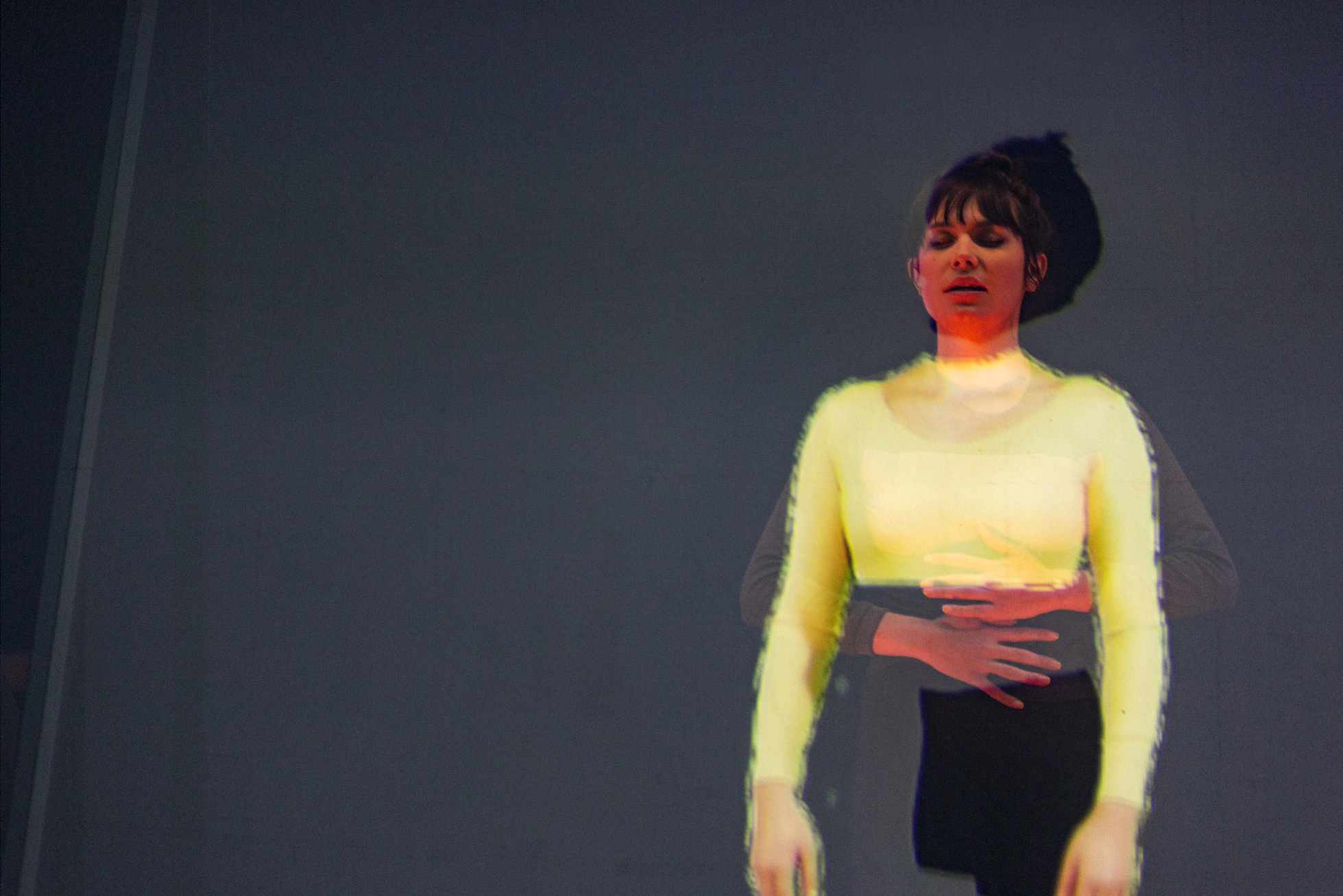

Visualizing Conception

Perhaps what makes Diaspora seem so remarkable as a performance work is the fact that the composition is, from inception, audiovisual. There is never the sense that the visuals are accompanying the sound—they generate each other, converging to activate the space creating the performativity. As well as Fox’s lasers that manifest the full-bodied vibrational sound as three-dimensional wave geometries, exquisite video projections, created by Nick Roux, hang suspended in air, the holographic illusion created by an enormous Pepper’s Ghost. [53] A meteorite emerges out of the depths of the space, making its way towards us. It almost imperceptibly transforms into a brain, an eye, multiple eyes, limbs. Fragmented body parts grow before us, eventually perfectly transposed over the live body of Darvidis, marking the artificial consciousness finding its form.

Georgina Darvidis, performance of Diaspora by Robin Fox (Chamber Made production, 2019) - Photo credit: Pia Johnson.

Saulwick: We had this completely separate development, which was around staging the body in relation to the hologram and what the visual language might start to be. …With the Pepper’s Ghost it becomes a set of pragmatic decisions: how to work with the architecture that the holograph projection surface offers you … There was some level of dramaturgy [around the body] being behind that structure and then revealing the live body at a certain point; breaking through to the foreground space and then being sucked back into the nether space … The live body, the digitized body, and the interrelationship between them.

It could be seen as potentially disappointing that the final digital consciousness takes a human form—is this the anthropocentric limit of our imagination? Will we always try to make our technology in our image? However, this is true to Egan’s text, in which the artificial consciousness has a choice of avatars but is eventually drawn to a human shape gleaned from its library of images. The work’s visual narrative guides us through this process of becoming, making us aware that what is being created is porous, contingent, and includes the potential of so much more.

In the same way that the composition shifts from linguistically musical to sonic, the visual language also shifts between figurative to abstract. The piece concludes with a spectacular explosion of light and sound (referencing the carving of a meteor in Egan’s text), in which Fox’s stadium concert pieces create the template, celebrating the bursting into sentience of this new consciousness. It’s an unabashedly, uncritical, and joyous celebration of a new digital, post-human life. While there may be causes for concern over the consequences of our increased transformation into digital life forms, they are left for others to argue. In Diaspora, the integration of the body within the digital entity attempts a hopeful trajectory that the notion of the corporeal will remain a component of an expanded consciousness. One of the burning issues of digital consciousness construction and substrate mind independence is around how a brain in a vat can sense its environment and replicate the kinesthetic knowledge this generates. In Diaspora, there seems to be the suggestion that corporeality remains significant (even if in some emulated form).

Conclusion: Linguistic Slippage

Evident in the artists’ own words and histories is the slippage between considerations of music and sound. As proposed in the Forum’s introduction, it is naive to think that sound theater is a completely separate activity to music theater. There is no damage done in thinking Diaspora a work of music theater, framed by music’s attendant “linguistic” qualities, as Fox terms it. However, it is also interesting and productive to consider the work’s origins in the non-musical, non-linguistic pursuits of sound and audiovisuality, and how this changes the compositional process; how audiovisual affect becomes narrative protagonist, suggesting a different form of performativity; and how this may mark a shift in “consciousness,” from music theater to electronic sound theater.

Gail Priest lives on the land of the Darug and Gundungurra people now known as Katoomba (Australia). Her practice encompasses performance, recording, installation, curation, and writing. She has performed and exhibited nationally and internationally presenting work in the UK, Iceland, France, Germany, Italy, Slovenia, Norway, Hong Kong, and Japan. Originally trained in theater, she has worked as a sound designer/composer collaborating with independent directors and choreographers. Also instigating her own sound theater work she has created One thing follows another, in collaboration with choreographer Jane McKernan, an exploration of Fluxus strategies in the twenty-first century; and We are Oscillators, in collaboration with designer Thomas Burless, exploring vocal cymatics, both works presented by Performance Space, Sydney. She has written extensively about sound and media art and was Associate Editor/Online Producer for the Australian arts magazine RealTime (2003–2015). She was also the editor of the book Experimental Music: Audio Explorations in Australia (UNSW Press, 2009). She is nearing completion of a PhD at the University of Technology, Sydney, exploring ficto-critical writing strategies in digital sound studies.

Opera Activism: Speechless—An Animated Notation Opera for Every Musician

Cat Hope

Speechless Teaser with Directors commentary from Tura New Music on Vimeo.

This article outlines the creative development of the opera Speechless (2017–19), composed and directed by Cat Hope. [54] At the conclusion of an evolving process of research, composition, workshopping, technical development design, and directorial concepts, the work was premiered at the Perth Festival in February 2019, performed by four solo vocalists, the Australian Bass Orchestra, and a mix of community choirs. The opera is a personal artistic response to global human refugee issues and is based on the 2014 Australian Human Rights Commission report The Forgotten Children. [55] This article explores the connections between the music, score, and production design of the premiere from the creator’s perspective.

Karina Utomo, performance of Speechless by Cat Hope (Tura New Music production, Perth Festival, 2019) - Photo credit: Rachael Barrett.

Pluralizing Form

Speechless is undoubtedly an experimental opera in its sound world and presentation realm, yet it is structured quite conventionally as it pertains to the opera genre—it has an overture, three acts, and an interlude. Each act consists of operatic formulas, such as arias, recitatives, and choruses. A range of traditional compositional techniques (such as theme, variation, development, repetition, retrograde, and inversion of material) are used throughout. Binary and ternary structures appear. The range of intensities of the music create the dramatic sound world you expect from the form.

That is where the links to convention cease. While the opera is sung, no words are used. The opera is designed to be performed by musicians from a wide range of music styles, not just classical or rock artists. The orchestra and choir are built from musicians in the city where it is performed and is composed, using color graphic notation that facilitates this polystylistic involvement. The four soloists are also required to be from different musical styles; and in the case of the premiere, there was a death metal singer, Karina Utomo; an exploratory vocalist, Sage Pbbbt; an opera singer, Judith Dodsworth; and opera/cabaret singer Caitlin Cassidy. The chorus was built from several community choirs and a public call, while the orchestra involved musicians from classical, jazz, rock, and folk styles. The Australian Bass Orchestra, for which the opera is written, is in fact a “mythical company” that only exists as a manifesto outlining a group of musicians who only play pitches below C4. Any musician can participate—as long as they can play these notes on the lower end of the spectrum —and the Bass Orchestra is named after the country where it comes together. The score captures this focus by specifying groups of low brass, low winds, low strings, piano, harp, electronics, percussion, and electric bass guitars.

Animated Graphic Scoring

Speechless (2019) (Score only) from cat hope on Vimeo.

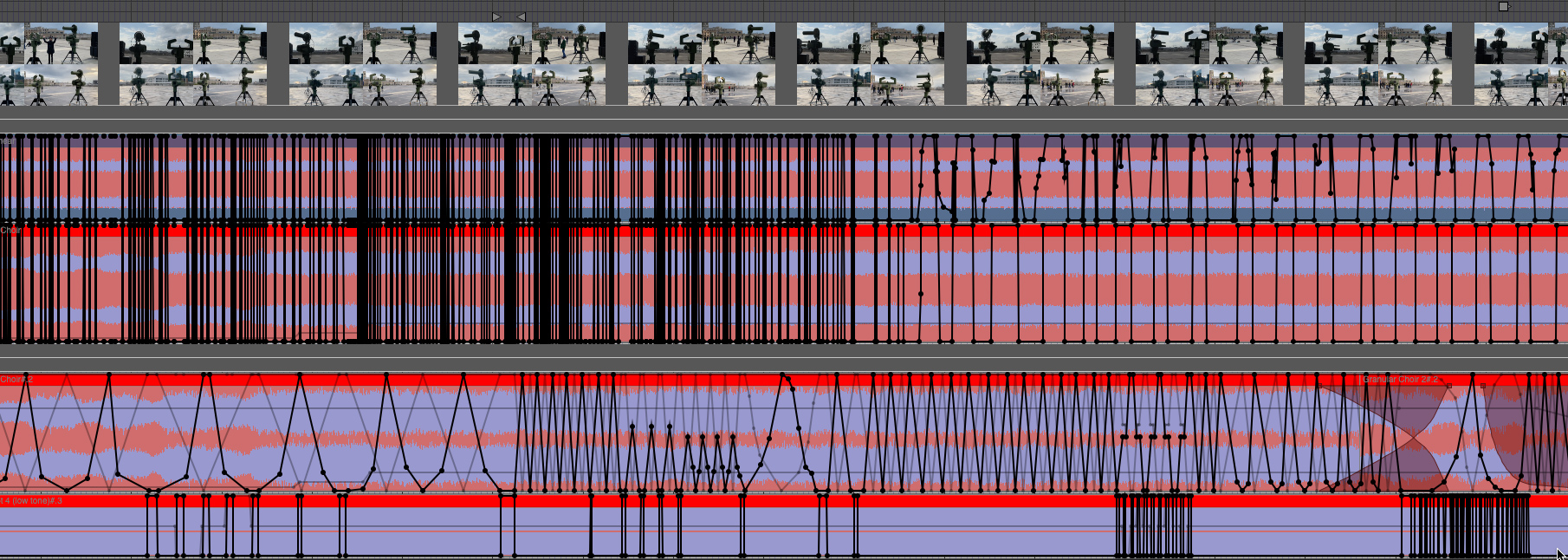

The score uses color graphic notation created digitally to develop image files to be read by performers in motion. [56] The score images outline all the instrumental parts but can be separated out as a series of layers, with each part highlighted for that group. The score is read as a “screen score,” presented to musicians in the Decibel ScorePlayer, an iPad application that animates the score image, by moving it across a “playhead” indicating the moment of performance. The application is developed by the Decibel new music ensemble, a group of musicians, composers, and programmers based in Australia. The musical director of the Perth premiere, Aaron Wyatt, is the programmer of this application and performing member of the ensemble, and I am the artistic director of and performer in the ensemble. The Decibel ScorePlayer application coordinates the networked reading of predominately graphically notated scores in rehearsal and performance. It features scrolling and “tracking” modes for score reading, as well as a range of other features such as the ability to annotate the score or change the part view without interrupting the progress of the score in motion. Having the music director so involved with the software ensured that any developments or changes to the application could be made during the development phase to accommodate the scale and unique requirements of the work and the processes around it—and this is what happened. During this project, it became clear that the automated score delivery system did not replace the need for a conductor, who provided reinforcement for the orchestra and gestural memory aids for the soloists and choir, who had memorized the score. The app also enabled the incorporation of the production cues for stage management, sound, and light. Also, a new way of quickly uploading changes to the score to multiple iPads was developed to facilitate the early workshops where the composer was working with all the musicians. The tablets are connected over a local network, which, when connected to a server, was also used to upload new and corrected versions of the score during the development workshops.

Artistic Activism

Speechless is my personal response to global human refugee issues, it does not at any time attempt to speak on behalf of refugees themselves. I felt very saddened by, and helpless in the face of, Australia’s response to refugees arriving in Australia. This is my attempt to respond to this key issue and encourage others to do the same, making the project a kind of artistic activism. [57] The report that the opera is based on, The Forgotten Children by the 2014 Australian Human Rights Commission (see supra), is a key document in the public learning about the treatment of refugees in Australia, particularly significant because it was rejected in the Australian parliament as “biased” when presented by the head of the AHRC, Gillian Triggs. As a result, people still languish in detention today, seven years after this report was issued.

Speechless by Cat Hope (Tura New Music production, Perth Festival, 2019) - Photo credit: Frances Andrijich.

The opera is very literally based on this report: the graphs in it are used as sources for musical “themes,” the color scheme of the report’s layout is used to describe parts for the choir, while the color scheme of the children’s drawings featured in the report are used to signal parts in the orchestra. The colors were sampled from the digital document and added to a “palette” used for all color decisions in the score. Further, the drawings and graphs in the report are engaged as core score material, manipulated, and transformed into images readable as music. It is almost a reversal of the libretto: the musicians “read” the report, while the singers do not use words: the libretto is effectively the score. The opera is designed to create and continue an emotional engagement with the Australian refugee issue and the politics surrounding it, for the musicians that participate and the audiences that experience it. It aims to create empathy for and sympathy with the issue, and hopefully spur people on to action to confront these issues. This was facilitated during the premiere season by providing platforms for refugee advocates before and after shows in talks, stalls, collections, and other opportunities.

Direction and Design

I directed the premiere, as I had a clear vision where the score, and thus the report, was clearly linked to all production decisions leading to its theatrical representation. I didn’t want a narrative for the opera—that would be a story that wasn’t mine to tell. Instead, the work consisted of a range of performance art actions, where the brief for the production team was “installation” and “performance art” rather than “theater” and “opera”—an installation approach to scenography. The themes for the design all link to the compositional processes and concept drawn from information in the report: shelter, connection, severance, joining, commonality, belonging/not belonging, following, isolation, memory, ephemera, long time passing, identity, missing parts, being trapped, and, of course, speechlessness (language and being heard).

Sage Pbbbt, performance of Speechless by Cat Hope (Tura New Music production, Perth Festival, 2019) - Photo credit: Toni Wilkinson.

I prepared for the direction and blocking of the show by reading film theory, Robert Wilson’s writing about “silent opera,” [58] and watching Romeo Castellucci’s theatrical productions. I particularly enjoyed Werner Herzog’s series of books Scenarios, which feature the free-flowing narratives he used as the basis of his films. [59] I set about writing my own scenarios for Speechless, which I remained quite faithful to in the end production. I plotted the action against the score, letting the music drive the decision-making process at every step of the way, and providing time frames for various settings. The way that my linear approach to graphic notation unfolds through time was very useful for plotting stage “action” through time as well. The music remained the driver for every aspect of the production design, and this helped me avoid didacticism as much as possible, retaining the abstract qualities I appreciate so much in music itself.

Judith Dodsworth, performance of Speechless by Cat Hope (Tura New Music production, Perth Festival, 2019) - Photo credit: Frances Andrijich.

I chose to work with Alex McQuire, a young fashion graduate, on designing the set and costume as one, where performers interact with their surrounds as extensions of their costumes, and vice versa. The stage design featured long reams of fabric hanging from above that the performers would engage with and transform into various objects as the work progressed. Performers would turn these large fabric pieces into costumes of various scales, backpacks, and pillows. These large fabric reams were intended as surreal surrogate flags—symbolic links to nationhood. Their scale and lack of symbols made them a kind of fictional, nondescript flag, but they still held the intention to describe a belonging of the past and of a potential future. The colors of these flags were selected from the children’s drawings in the report, according to the same color scheme used for the orchestral parts, as a way to link the set to the score and, thus, the music to the set. Each vocal soloist is ascribed a flag color, but that was not necessarily the color of their part in the score, further complicating this notation of “belonging.” The flags were over fifteen meters long, and their bright, solid block colors cascaded down from the roof space onto a black carpeted stage—the carpet being the type found in government offices. Also inspired by the waiting rooms in government offices were the audience seats. These were placed “in the round,” on the edge of the carpet that defined the stage area, with the orchestra at one end. The choristers were placed among the audience, dressed simply.

I ascribed directorial approaches for each flag color: formality (blue), surreal occurrences (red), dramatic tendencies (green), and emotional responses (pink). Three of the four flags were made of tent fabric, which made its own sound when handled, resembling some of the extended vocal sounds made by the soloists. The pink fabric was the exception. It was a sensuous jersey type; soft, stretchy, pliable, and silent. During the performance, the blue, red, and pink fabrics were pulled down from their flag-like hanging position, each in different ways, at a different pace, and for a different purpose. The red was fashioned by the soloists into an extended, oversized backpack the length of one performer, who trailed it around behind them for most of the show. The blue length was folded by the soloist ensemble using formal flag folding techniques, accompanied by a recitative, and attached to that performer in a way resembling a Japanese obi, as an extension of her existing costume from the same fabric. The pink flag was dramatically and quickly whipped away at the beginning of a loud, screeching solo, then gathered up into a kind of portable, cushioning backpack. The green flag was different from the others, in that it had the arms of used clothes sewn into it, referencing the 2001 “Children Overboard affair”—a political controversy where Australian government ministers falsely accused seafaring asylum seekers of throwing children into the sea to secure passage. This flag was stored under the conductor’s podium until the soloists ritualistically drew it out, collectively fashioning it into a spectacular and elaborate gown, beautifully designed by assistant director Rakini Devi for the only opera singer. This aimed to highlight the extra attention given to the opera art form at the expense of others, whilst linking to the theme of the work. These different engagements with the flags were the focus for the majority of action that took place on stage throughout.

The space was hung with vertical LED lights, referencing the bars found in many of the children’s drawings from the report, in association with other top-down lighting that was plotted to unfold as very slowly moving washes that transitioned across the space, bathing it in red, to moments where the light responds to the music and soloists voices (designed by Matthew Adey with Andre Vanderwert). The choir, divided into four musical parts, each aligned with one of the soloists, interacts largely with the soloists both musically and in terms of action. The choir moves as a whole at certain points, en masse, referencing what was known as Donald Trump’s caravan “invasion,” a group of over four thousand migrants travelling across Mexico toward the United States in 2018. At one point in the opera, the choir and soloists lie on the floor in the dark, as the room sings with feedback scored for the interlude. They lie with nothing for comfort, only to arise and begin their wander again.

Affective Frequencies

The music focuses on very low sound worlds across both high and low volumes. This low sound can create vibrations in the room and listeners themselves, shown to produce more emotional responses. Drones and long, sliding tones are the predominate features that replace melody and tonal harmony, facilitated by my personal notation approach that eschews traditional notation design. The range of pitches (below C4) is decided by the players themselves, but my composition prescribes the way these pitches relate to each other. Each group of instruments (e.g., low brass) forms a microtonal cluster, represented by a singular color. The work features improvisational moments for the soloists and various members of the orchestra, inviting them to strike out from the larger group and showcase their unique style. While the audience cannot see the notation, there is a strong connection between color and sound throughout this production, not in any synesthetic sense, but more as a way to connect and express the material from its source. The diverse range of musical styles creates a unique sound imprint that generates a sound world difficult to categorize, and the critical review and audience surveys demonstrated that the work did elicit emotional responses and a heightened motivation to act in empathy with those seeking better lives through asylum.

The audience and media review responses to the premiere season were overwhelmingly positive, with sold out houses over a six-show season. The scoring technique enabled a more open participation for musicians from a wide range of stylistic backgrounds, but also facilitated the unique qualities of the work, such as the focus on long form, drone like sound, extended glissandi, extended techniques, and sections of free improvisation. It enabled the linking of sound, light, and other stage management cues into the musical score and thus the conductor’s involvement, resulting in these aligning very precisely with the musical material. It also drove and enabled the high level of abstraction that is at the core of this composition and its production design.

Further reading

Crotty, Joel, and Cat Hope. “Speechless: An Operatic Response to

Human Rights Abuses in Twenty-First Century Australia.” In

Opera, Emotion, and the Antipodes Volume II: Applied Perspectives:

Compositions and Performances

, edited by Jane W. Davidson, Michael Halliwell and Stephanie Rocke, 75–89.

London: Routledge, 2020.

Hope, Cat. “The Future Is Graphic: Animated Notation for Contemporary

Practice.” Organised Sound 25, no. 2 (2020): 187–97.

—. “Infrasonic music.” Leonardo Music Journal 19 (2009): 51–56.

—, and Lindsay Vickery. “The Aesthetics of the Screen-Score.” In Proceedings of CreateWorld 2010, edited by Michael Docherty,

48–57. Brisbane: Apple University Consortium, 2011.

—, Aaron Wyatt, and Daniel Thorpe. “Scoring an Animated NotationOpera—The Decibel Score Player and the Role of the Digital Copyist in Speechless.” In

Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Technologies for

Music Notation and Representation–TENOR ’18

, edited by Sandeep Bhagwati and Jean Bresson, 193–200. Montreal: Concordia

University, 2018.

James, Stuart, and Lindsay Vickery. “Representations of Decay in the Works

of Cat Hope.” Tempo 73, no. 287 (2019): 18–32.

McAuliffe, Sam, and Cat Hope. “Revealing Sonic Wisdom in the Works of Cat

Hope.” Organised Sound 25, no. 3 (2020): 327–32.

Milligan, Kate B. “Identity and the Abstract Self in Cat Hope’s Speechless.” Tempo 73, no. 290 (2019): 13–24.

Cat Hope is a composer, sound artist, performer, songwriter, and noise artist. She is a classically trained flautist, self-taught vocalist, experimental bassist, and is the director of Decibel new music ensemble. Her music is conceptually driven, using animated graphic scores, acoustic/electronic combinations and score reading technologies. Her music has been discussed in books such as Hidden Alliances (Schimana, 2019), Sonic Writing (Magnusson, 2019), Loading the Silence (Kouvaras, 2013), Women of Note (Appleby, 2012), Sounding Postmodernism (Bennett, 2008) as well as periodicals such as Gramophone, The Wire, Limelight, and Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. In 2011 and 2014 she won the Award for Excellence in Experimental Music at the Australian Art Music Awards, and her opera Speechless won the Best New Dramatic Work category in 2020. Her music has been played around the world, and she is a Professor of Music at Monash University, Melbourne, Australia.

Performing Installations: An interview with Kathy Hinde

Matthew Sergeant

Kathy Hinde, performance of Twittering Machines - Live AV (2019) - Photo credit: Ashutosh Gupta.

Kathy Hinde was the winner of the Sound Art category at the 2020 Ivors Composer Awards, taking the prize for her live work Twittering Machines (2019). [60] Hinde’s output is broad. Her work includes gallery installations, public participatory projects, and sound walks, as well as work that fuses all these elements and more. Twittering Machines — Live AV is her first self-contained performance work, although for many years she has repurposed her more sculptural installation works as instruments with which she performs. It was this interrelation of installation and performance that I wanted to pick at as I met with Kathy (remotely) during the UK’s third national lockdown in Spring 2021.

Kathy Hinde: The performance version of Twittering Machines grew from an installation of mine of the same name—along with the necessity to respond to an invitation to perform without being able to “ship” an installation. I had been experimenting with various different “tabletop” sound making set-ups for years, and so this performance grew from these previous experiments—so in this case it did evolve substantially from the original installation work.

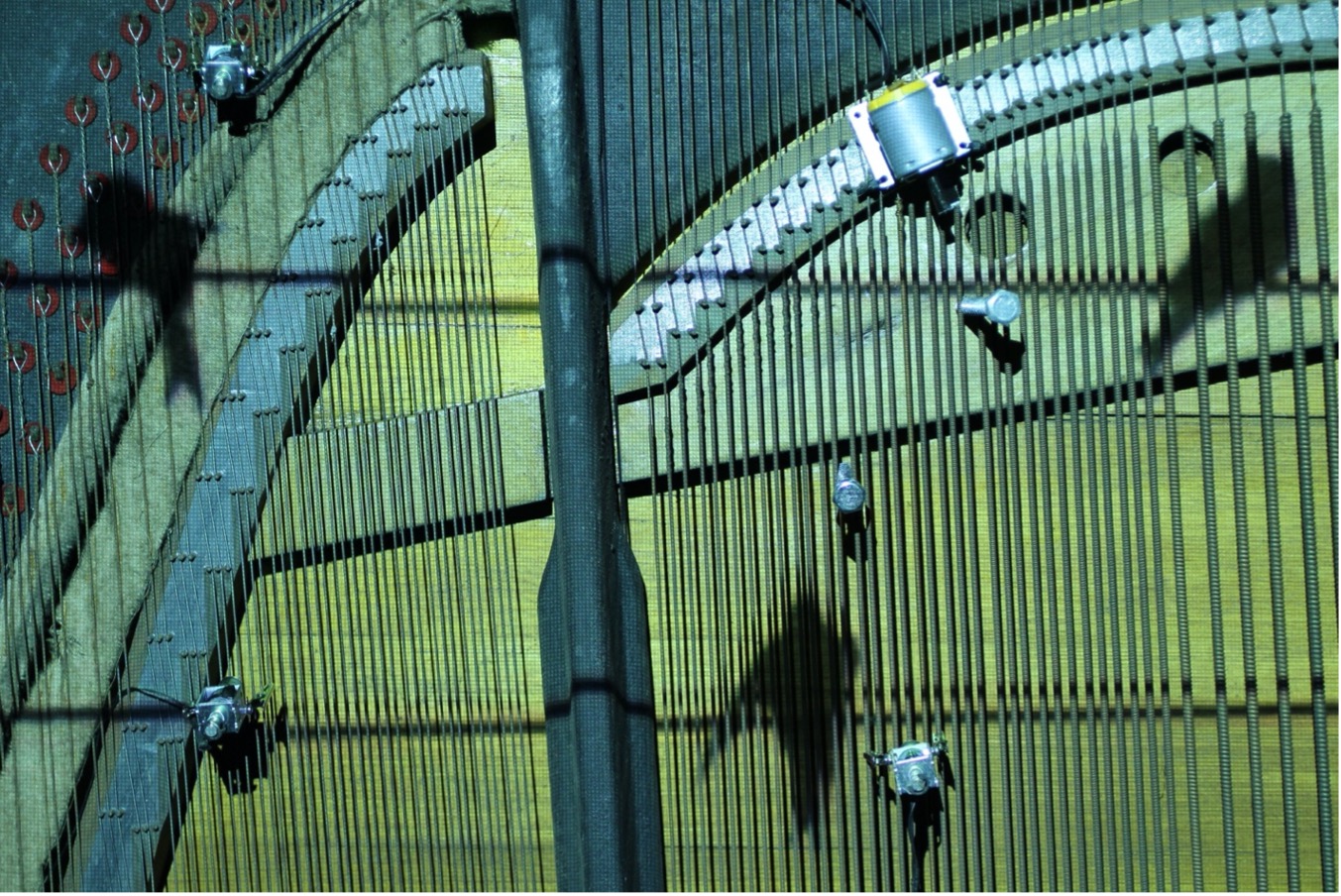

Hinde’s practice of repurposing her instruments began with Piano Migrations in 2010, which presents videos of birds projected onto the strings of a physical piano. The videos appear to interact with the strings of the instrument through twangs and strums produced by computer-controlled tappers and exciters, seemingly bringing the instrument to life. A later piece, Tipping Point (2014), presents six pairs of connected water jars hung from mechanical arms, controlled by motors to oscillate like seesaws. As the water self-levels across the moving jars, it serves as a mechanism for tuning audio feedback.

Hinde: I first started thinking about my installations as instruments I could perform with live after I’d created Piano Migrations. Despite the main body of the piece being a dismantled piano with all the regular “playing” mechanisms removed, it was only when the work was finished that I realized I could still “play” it [through software]. When I later embarked on the creation of Tipping Point, I then had the premeditated intent to design an installation that could also be the site for live performance. In fact, Tipping Point started a trajectory of work that I feel slips between “sound sculpture” and “invented musical instrument.”

There is therefore a clear connecting thread of performativity across Hinde’s work. Even when installed, Hinde’s works never simply are, they do. When the artist is not performing, Tipping Point sways in a slow dance. And while we are aware of motors whirring under computer control, it also appears as if the water is singing. This dialogue with the performative properties of her materials is something she continually acknowledges in our conversation.

Hinde: Tipping Point looks quite “precise” and “designed”, but the way it works is actually quite emergent. The work is all about audio feedback. I don’t “make” the sound, but instead set up the conditions from which sound can emerge through resonant frequencies. [In performance] I can shift the glass vessels to change the water levels, but I then have to listen closely to wait and find out what my adjustments have changed, and then respond back. It’s a balancing act—a dialogue—and in this way it relates to the physicality of sound and how it behaves in space. I can’t control it fully and precisely.

From this perspective, I was keen to understand more about Hinde’s relationship with her materials. Given that sound always seems to lie within the core of her audiovisual interdisciplinarity, it was perhaps unsurprising that, when the topic of materiality is broached, she is first keen to talk of the materiality of sound itself.

Hinde: One vivid listening experience was on a residency in Bavaria in 2014. I was exchanging “quiet environmental sound recordings” with sound artist Tony Whitehead. Tony sent me a beautiful recording of a leaf, gently, and only slightly, moving in the wind. It was very quiet, yet evocative. I was listening on headphones whilst reading indoors. The window was slightly open and when I listened to the leaf moving in the wind, I became aware of a slight cool breeze on my cheek. I listened to the recording for a second time … and, yet again, I became aware of the breeze on my cheek. It was somehow spontaneous and intuitive; which got me thinking. Through listening, I seem to have started to have more of a multisensory experience—and engaged in “touch.”

Tipping Point by Kathy Hinde (2014) - Photo credit: Kathy Hinde.

The sense of tactility with which Hinde describes materials permeates our conversation. When Hinde mentions the materials with which she is working, it is never far abstracted from her sense of physical contact with them.

At this point my mind wanders back to the whirring motors that lie behind the slow liquid dances of Tipping Point. A digital/technological presence permeates much of Hinde’s work. Her live performances frequently combine live digital manipulation, analog records, and objects motor-manipulated via a computer. Her installations are often controlled through Max patches. I wondered how this tactility might apply to these domains.

Hinde: I perform live with Piano Migrations, as a duo with Matt [Olden]. I do this by choosing different videos of birds to project onto the piano—and this can produce surprising responses. Through the Max patch, I can control the sensitivity of the translation into physical “twangs”— and I can also control the speed of the movie and the “repeat rate” of the “twang”. So, I place the video on the piano and then respond and shape how it responds by listening and observing. So, again, it’s something I don’t have complete control over—even more so than Tipping Point perhaps.

Hinde has collaborated with Olden for over a decade, beginning with Piano Migrations in 2010.

Hinde: I work on the overall “system” for a piece and what part the Max patch plays within it, but collaborator Matt Olden actually programs the Max patches and I’m not as intimately involved in this. The fact I don’t make the Max patches myself probably does make a difference conceptually for me, especially in comparison to my soldered circuit boards and machined, mechanical parts

Piano Migrations by Kathy Hinde (2010) - Photo credit: Kathy Hinde.

It’s interesting that I don’t make my own software in this respect. I suppose it’s quite hard for me to consider how a Max patch might have [the same] material qualities as my soldered circuits. I’m quite attached to my laptop. I don’t like being without it. But I’d say that Matt Olden’s computer is an extension of his mind and body in quite a different way. In that way, the Max patch doesn’t present the same kind of discursive materiality for me—but that is different for Matt, he is his machine.

Hinde’s description of Olden’s laptop as a quasi-prosthesis to his body (in a way hers is not) is beguiling. It seems Hinde identifies the same tactility in Olden’s relationship to code as her own relationship with, say, welded steel. In this creative partnership tactility still seems to function as a form of common currency.

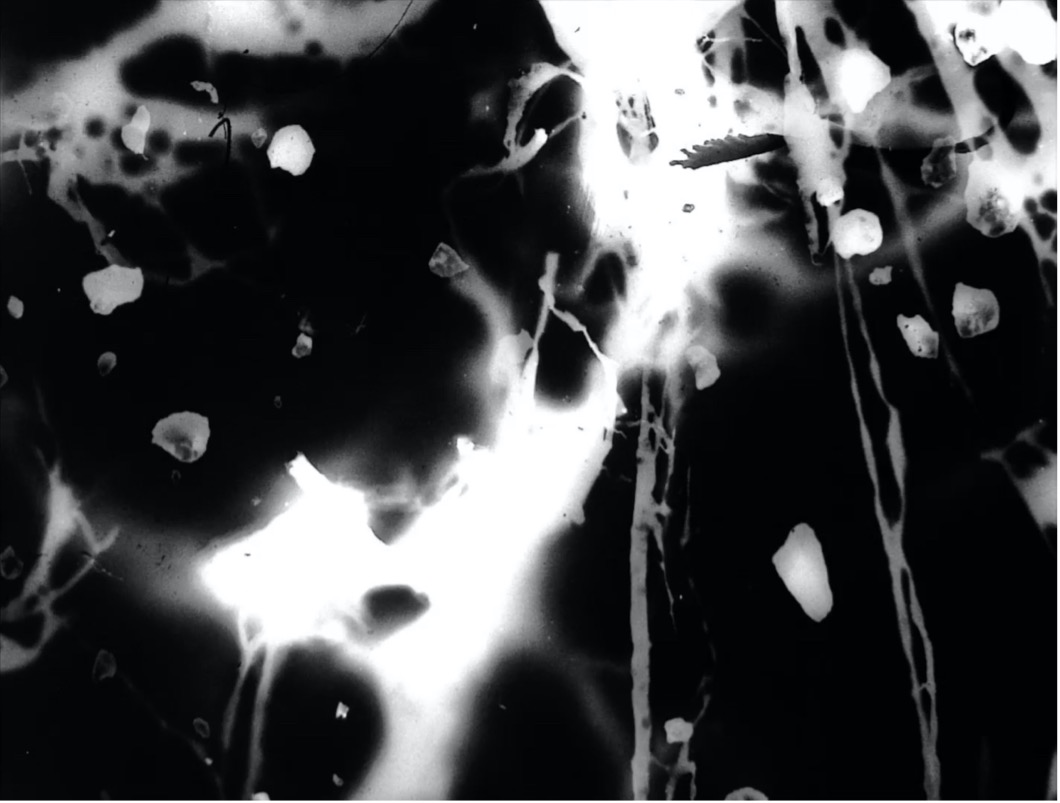

Such conversation reveals an underlying dialogic quality to the performative aspects of her work in this regard, with words like “listening” and “responding” frequently reappearing. I was interested as to whether she saw her materials as a form of collaborative co-author or co-agent in this regard, to which she responded by discussing her recent audiovisual piece River Traces 1 (2020), her first work with 16mm film. [61]

Hinde: I spent a lot of time recording and listening to the river—running my hands in the water, exploring the textures of the plant life, mosses, and rocks through touch. I started to make photogram 16mm films with river materials—(my first photogram film)—and I found it so very tactile. This film-making process felt like a very intimate encounter with both the material qualities of the river and with the process of making an analogue film in this way. What I discovered through these experiments is that film is sensitive. It collaborates. It responds back and improvises. There is a high possibility that what you set out to do will come out “differently.”

“So, your materials are a collaborator in this sense?” I asked her outright. Her answer surprised me.

Hinde: Actually, I’m not sure that “collaboration” is the right word in this context. The reason I’m not one hundred percent comfortable with it, is that … how can the river actively take part? And how can this be an equitable collaboration? I think that the term “collaboration” was a useful conceptual tool when approaching my creative processes with the river. I enjoy thinking about it as a collaboration, which gave rise to subtle shifts in my approach and perception. But my reservations are to do with the fact that the river does not actively give me permission. My premeditated approach—that I intend to consciously leave space for the river to “do its own thing”—gives some agency to the river, but I am not able to sense the “intention” of the river or find a way to hand the same amount of agency that I have over to the river.

I asked her to elaborate further.