ARTICLE

The Afterlife of a Lost Art: On the Work and Legacy of Silent Film Pianist Arthur Kleiner *

Anna K. Windisch

Sound Stage Screen, Vol. 2, Issue 1 (Spring 2022), pp. 71–105, ISSN 2784-8949. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. © 2022 Anna K. Windisch. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54103/sss17494.

Audiences attending the silent film screenings at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City between 1939 and 1967 most certainly witnessed the live piano accompaniment of a Viennese-born emigrant: Arthur Kleiner. For decades Kleiner embodied the “lost art” of silent film accompaniment, which had slowly come to an end with the commercial introduction of the technically synchronized sound film in the late 1920s. Beyond the affectionate, honorary title as the “world’s only full-time silent movie pianist,” [1] his job entailed the research, composition, compilation, and performance of piano scores for hundreds of silent films during his twenty-eight-year tenure at the MoMA until he left New York City in 1967. In the remaining thirteen years of his life, which he spent with his family in Hopkins, Minnesota, he devoted himself to touring, teaching, filmmaking, and researching, as well as to the writing of a monograph on film music, which remained unfinished. One year after his death in 1980, his wife Lorraine Kleiner donated his extensive library of music scores (printed scores and manuscripts for nearly 700 silent films), sheet music, books, tapes, broadcasts, and other material to the University of Minnesota. Today, it forms the Arthur Kleiner Collection of Silent Movie Music, which serves as an invaluable resource for the research on silent film music practices and stands as a testimony of the influence and accomplishments of Kleiner as an artist. In spite of the fact that Kleiner, ironically, embodied the most persistent cliché of silent film music––the lonely pianist––he dedicated his career to restoring and performing original orchestral scores and to teaching the wide array of musical practices that once characterized the live music played in cinemas during the first three decades of the twentieth century. Thus, for historians of film culture, Kleiner remains an essential point of reference to reconstruct and discuss the status of silent cinema music during the sound era, particularly during a time when silent films were being presented in complete silence in some film preservation institutions and the music performed for silent films was frequently reduced to trivial clichés. It was not until the revival of silent cinema in the 1970s that original scores and music for silent films regained broader attention as part of the “elevated cultural status that relatively recently has become associated with silent films.” [2] Kleiner’s career could thus be summed up as that of a pioneer who attempted to assert (silent) film music’s place in music history and to reestablish film music as a legitimate artistic medium.

I begin my article by providing some historical context regarding the establishment of the Film Library at the Museum of Modern Art in 1935 and by tracing the prevalent tendencies of exhibiting silent cinema in a museum context in the mid-twentieth century. I then examine Kleiner’s artistic background and his career as a pianist, dance, and theater accompanist, composer, and conductor in Europe, which emerge as influential aspects in shaping his creative methods and his approach to film music research as well as his attitude to representing silent cinema in general. After that, I deemed appropriate to insert a brief discussion of the meaning of the term “synchronization” with regard to silent film music. Rather than providing a chronological account of Kleiner’s career milestones and activities, the remainder of my article looks at three key roles Kleiner assumed during his career as silent film pianist: first, as a historian and musicologist who saved and reconstructed historical material; second, as a composer and compiler who produced new material for this lost art; and finally, as a performer who offered his dramatic interpretation of the films and publicly epitomized the image of the silent film pianist. Concluding my observations is a close analysis of a documentary about Hollywood film composers written by Kleiner in 1972. Highlighting Kleiner’s self-perception as an artist by drawing on Philip Auslander’s concept of “musical persona,” I argue that he tried to position himself in-between Europe’s musical heritage and (American) musical modernism, not least as a means of artistic self-actualization.

Preserving a Lost Art: Silent Film Exhibition during the Sound Film Era

The Museum of Modern Art, founded in 1929, played a major role as a public institution in defining and navigating the perception of film as a genuine American art form and of American culture more broadly. MoMA was not the first cultural institution to include film as a key expressive form worth preserving: in 1915, Columbia University had started its first film program; ten years later, Harvard University not only established films as part of their curriculum (most notably in Paul J. Sachs’ celebrated Museum Course) but also discussed the establishment of a film library. [3] Although the latter did not come to fruition, the influence of these interferences with the film industry reverberated, as Harvard graduates—among them, future MoMA director Alfred Barr—“went on to found MoMA’s Film Library and define the class of film experts who moved fluidly between film production, government work, and arts administration,” [4] as Peter Decherney asserts. Barr considered film “the only great art form peculiar to the twentieth century” and thus worth preserving and collecting. [5]

The Museum’s Film Library, established in 1935 thanks to the efforts of British film critic Iris Barry, its first curator, fulfilled the functions of a cinémathèque in the classical sense by presenting a canonized selection of works in their cycles and retrospectives, and from the outset oriented itself towards educational aims of presenting cinema history and the medium’s development as an art form. The Film Library was not merely an alternative exhibition space, but rather a cultural force that, through collaborating with both Hollywood studios and government agencies, impacted the national film industry and film culture, and most of all the popular conception of American cinema through canonization and an eclectic programming structure. As far as the musical accompaniment of the silent films presented at the Film Library’s cinema was concerned, Barry was convinced that only in recreating the historical viewing conditions would the filmic experience lead to a proper appreciation of silent films, as she stated in the inaugural program: “It is the aim of the Film Library to approximate as nearly as possible the contemporary musical settings of the films it will show on its programs.” [6] Barry was sensitive to the fact that music was an integral part of silent film exhibition and in her regular communiqué to the Museum’s members she addressed aspects of the historical development of film accompaniment such as the emergence of film music tropes in conjunction with cinema stock music libraries.

In the Mary Pickford picture, The New York Hat, Miss Beach has overlaid the thematic strain with “gossip” music which simulates the sound of gossipy voices, feminine and masculine. This is in true movie tradition, for as musical accompaniment grew with the motion picture it developed into distinct types known as “love music,” “hurry music,” “battle music,” “mysterioso music,” and so on. [7]

Barry’s comments suggest that not only was film considered a historical object to be presented in a museum context, but that cinema music, as part of this exhibition model, was in itself a tradition worth preserving.

This approach to reconstructing the historical musical accompaniment of silent films cannot be taken for granted for institutions preserving and exhibiting silent cinema in the post-silent film era. On the contrary, the Cinémathèque française, established in Paris in the mid-1930s around the same time as MoMA’s Film Library, famously screened silent films in complete silence and elevated what might have partly resulted from a lack of economic resources to an aesthetic paradigm, which considered films as historical objects that should be beheld without any distraction, musical or otherwise. Other institutions followed suit. In Vienna, the Österreichische Filmmuseum (Austrian Film Museum), founded in 1964 by Peter Kubelka and Peter Konlechner, showed foreign films in their original language without subtitles and rejected any kind of introductory lectures or musical accompaniment for silent films, explicitly citing the work of Henri Langlois, co-founder and director of the Cinémathèque, as their example.

Another film preservation center famously adopted this notion only a few

years later: the Anthology Film Archives (AFA). The key personalities

involved in the foundation of AFA in 1969, whose initial idea dates back to

the early 1960s, were Stan Brakhage, Jonas Mekas, Peter Kubelka, Jerome

Hill, and P. Adams Sitney. A significant transatlantic connection emerges

when looking at the histories of AFA in New York and the Austrian Film

Museum: AFA’s exhibition space, the so-called

“Invisible Cinema,” was designed by Austrian filmmaker Peter Kubelka and it

became the paradigm of modern film exhibition in avant-garde and cinephile

circles. Kubelka’s design essentially evoked the individual experience of

the peephole show by minimizing any visual or sonic distraction during the

viewing process. Kubelka added “large black hoods on each seat to reduce

the awareness of other audience members.”

[8]

The entire theater was draped in black, and the viewer had no “sense of the

presence of walls or the size of the auditorium. He should have only the

white screen, isolated in darkness as his guide to scale and distance.”

[9]

The idea of screening silent films without musical accompaniment was

publicly championed as early as 1915 in American poet Vachel Lindsay’s

famous treatise The Art of the Moving Picture, in which he

stressed the sociological potency of cinemas as communal spaces and

suggested to eliminate musical accompaniment so that patrons were

“encouraged to discuss the picture.”

[10]

Around five decades later, film intellectuals and avant-garde filmmakers

cited aesthetical reasons for dispensing with the musical accompaniment.

They elevated silence as the only true accompaniment of silent films as

historical objects. Eszter Kondor observes: “The respect for the film—as

artifact and projection experience—was the principal concern for Konlechner

and Kubelka.”

[11]

The argument went that since the manifold forms of musical accompaniment

during the silent period had not been part of a director’s vision, they

bore no historical relevance on the films.

[12]

This assumption, however, is easily challenged if we look at the diligence

and degree of involvement with which some early film directors

(particularly D. W. Griffith) approached and controlled the musical

accompaniment of their films, or when we consider the array of original

scores that were composed for feature films between 1915 and 1927. Regarded

as the “cinephile mode of viewing silent films”—which considered the

presence of music a distraction from the film’s status as an aesthetic and

historical object—this exhibition mode contributed to the notion of the

hierarchy of images over sound in cinema, a paradigm that shaped the

perception of silent cinema for generations. Carried out both in film

museums and university classrooms, this historically dubious practice of

projecting silent films without any accompaniment was hardly user-friendly

and had profound consequences for the reputation of silent cinema among the

general public.

MoMA’s Film Library opened its doors less than a decade after sound films had replaced silent films in movie theaters, a phenomenon which had instantly changed perceptions of silent cinema. Film audiences readily absorbed the reception conventions of the sound film and silent films became a curiosity, old-fashioned, and even uncanny. Mary Ann Doane observed in 1980:

The absent voice re-emerges in gestures and the contortions of the face – it is spread over the body of the actor. The uncanny effect of the silent film in the era of sound is in part linked to the separation, by means of intertitles, of an actor’s speech from the image of his/her body. [13]

Charles L. Turner recalled the initial silent film screenings at MoMA in January 1936 as awkward experiences for filmgoers:

People coming in didn’t know how to react to silent films. This was something from the past. They were uncomfortable, a little nervous about it. Perhaps some didn’t want to be thought stupid. The reaction of some was to laugh at anything that wasn’t absolutely current in style or performance. [14]

Live music was particularly crucial to the suddenly silent screen, after viewers had become accustomed to (often uninterrupted) musical underscoring and most significantly to hearing the actors’ voices in sound films. It would take another three years after the founding of the MoMA Film Library until an emigrant from Vienna would enter the projection room for the first time to help breathe new life into the moving yet mute images.

From Europe’s Theater Stages to MoMA’s Film Library

Arthur Kleiner was born on March 20, 1903, into a bourgeois Jewish family in Vienna. His family background was a musical one and his parents associated in intellectual and artistic circles. Kleiner was hailed as a child prodigy for his talents on the piano and one of his earliest acquaintances studying music as a young boy was Erich W. Korngold, who was six years his senior. [15] In 1921 Kleiner graduated from the Academy of Music and Performing Arts and soon took engagements as piano accompanist for different dance and theater groups between 1920 and 1925, touring Germany, Hungary, Bulgaria, and other Eastern European countries, besides performing recitals as organ soloist at the Wiener Konzerthaus and at the Musikvereinssaal.

In the 1920s, Kleiner absorbed the artistic and intellectual life of Berlin with its liberal social attitudes and exuberant creativity while working as accompanist for one of the most scandalous dancers of the Weimar Republic: Anita Berber. Kleiner reminisced about Berlin during the “Golden Twenties”:

Berlin was a fantastic place to be in the 20’s too, when I was there: drug sellers of cocaine, right on the street, the immorality was terrible, the crime worse than Chicago at the same time because Chicago’s only involved murder and gangsters. Berlin’s corruption involved civilians and was worse than murder, somehow, more insidious. … I played piano accompaniment then for Anita Berber, the famous nude dancer of the time in night clubs, who always had some scandal attached to her name … it was quite a place, Berlin. [16]

Clearly impressed by his experiences in the German capital, Kleiner returned to Vienna in the late 1920s and taught stage music and chorus at the renowned acting school Max Reinhardt Seminar. Besides teaching music to aspiring actors, Kleiner wrote stage music for the Seminar’s plays given at the Schönbrunner Schlosstheater. He continued his collaboration with the school’s famous namesake director on several stage productions and in 1933 Kleiner conducted the Mozarteum Orchestra in a production of Felix Mendelssohn’s Ein Sommernachtstraum ( A Midsummer Night’s Dream) under Reinhardt’s stage direction at the Salzburg Festival. Two years earlier, the Wiener Symphoniker had performed Kleiner’s original ballet Birthday of the Infanta, based on Oscar Wilde’s short story, at the Konzerthaus in Vienna.

While Kleiner was immersed in Vienna’s musico-theatrical scene, the Austrian film industry began its transition to sound film around 1930. Curiously enough, film did not attract his attention yet in these years, and his first encounters with silent cinema (music) had been rather sobering:

I remember seeing Eisenstein’s Potemkin in a small town outside Vienna for the first time, with piano accompaniment (Sousa marches, etc.) and it was the first time I saw a pianist accompanying a film. I had no leanings towards this myself, however. … I was theatre crazy, all Vienna was theatre crazy. [17]

By the late 1930s Kleiner’s Jewish heritage threatened his existence in Vienna. Thus, at thirty-five years of age and looking back at an eighteen-year-long career as composer, arranger, performer, and conductor for modern dance and theater groups throughout European capitals, the political situation forced him to leave the country. After arranging the transport of his beloved Bösendorfer grand piano, he arrived in the United States via London in the fall of 1938. Working with such luminaries as Reinhardt in Europe may have paved the way for Kleiner to seamlessly resume his career after arriving in the United States, where he collaborated with another stage coryphaeus: George Balanchine, one of the most influential choreographers of the twentieth century and among the founding fathers of the American ballet. Kleiner soon learnt to appreciate also the musical skills of the famous dancer who “would often sit and play four-hands” with him during rehearsal breaks. [18] Kleiner’s stint as rehearsal accompanist with Balanchine lasted only a few months—likely because Balanchine was about to relocate to the West Coast to pursue his touring company American Ballet Caravan. Around the same time, Kleiner began collaborating with dancer and choreographer Agnes De Mille.

The exact circumstances as to how Kleiner ended up at the Museum of Modern Art in 1939 remain lost to history. One of Balanchine’s associates claims that he told Kleiner about a temporary position at the Museum to accompany silent films and that, intrigued by this prospect, Kleiner went to see Barry, who is known to have “helped many Jewish filmmakers find employment in America.” [19] Another version in which Barry sought out Kleiner is recounted in an interview on the occasion of Kleiner’s retirement:

In 1939 when he was approached by Iris Barry, first Curator of the Museum’s Department of Film, to play for the Museum’s screenings, she asked him if he could play ragtime. He recalls, “I said ‘yes,’ even though the only ragtime I knew, as the music meant nothing to me, was the rag by Stravinsky.” [20]

Kleiner’s tongue-in-cheek claim that the only rag he knew was Stravinsky’s Ragtime for Eleven Instruments (1918) for small chamber orchestra, hints not only at his personal musical preferences, but foreshadows his struggle for artistic self-actualization within the commercialized image of the film industry, an inner conflict that would accompany Kleiner throughout his life. In whichever way the first contact was established, Kleiner was faced with a challenge that was different than anything he had ever done before. He was hired on the spot for a three-month trial period which did not entail ragtime, as he did not miss the chance to mention in subsequent interviews, but instead turned into a twenty-eight-year long engagement as music director of the Museum of Modern Art’s Film Library. Dance and theater fan Kleiner thus entered one of the world’s foremost institutions for promoting cinema, and silent cinema in particular, as an art form—a conviction which Kleiner fostered and that would penetrate his own sensibilities when he declared his personal preference for silent over sound films. He had, however, personal reasons not to dismiss the latter: “I am grateful to the talking pictures for one thing. When I first came over I went to the talkies every spare minute I had. And that’s how I learned to speak English.” [21]

Synchronization in Silent Film, Dance, and Pantomime

Before I delve into details about Kleiner’s work as a researcher and about his process of fitting music to images, it seems appropriate to spend some time clarifying what the term “synchronization” actually meant in the broader context of silent film accompaniment. A general assumption exists, certainly in public but it continues to linger among scholars as well, that the synchronization of images and sound in cinema only came to fruition with the introduction of sound film technologies in the late 1920s. There is, however, ample evidence to suggest that the precise matching of images to music was of great concern and very often achieved during the silent film era. [22] Granted, elaborately synchronized musical scores were subject to financial considerations and largely limited to metropolitan, deluxe picture palaces, but the absence of the spoken voice in most silent films did not preclude a very carefully designed musical score meant to run in synchrony with the images.

In an article that traces the contiguous developments of music for pantomime and cinema, leaning on Carlo Piccardi’s 2004 study “Pierrot al cinema,” [23] musicologist and conductor Gillian Anderson eloquently lays out the connections between composing for pantomime and ballet and the techniques used in silent film scoring, stressing that “there was synchronized sound before the advent of talking pictures,” [24] a notion which Kleiner’s work palpably demonstrates. Anderson notes: “The word ‘synchronization’ appeared often to describe the moving parts of a machine, but it came to be used to designate the matching of sound with mechanized moving images.” [25] The process of matching sound and images was facilitated via cues notated in the score for the appropriate synchronization with the moving images. In silent film accompaniment these cues are generally connected to intertitles or changes in the mood, time, or place of the screen action. Hollywood film music practitioners, as well as present-day silent film musicians such as Anderson or Frank Strobel, use the term “sync points” when describing such cues. In his seminal study on film music, Sergio Miceli distinguishes between explicit and implicit sync points (sincroni espliciti, sincroni impliciti) of music/sound and moving images.

An explicit sync point is the exact and unambiguous correspondence between a filmic and a sonic/musical event: at times, the music ‘doubles’ the sound by superimposition, and imitates it. An implicit sync point is a more subtle conjunction: this category comprises changes in timbre, harmony, rhythm, dynamics, the beginning or conclusion of a melodic fragment and any musical event/parameter as long as it is linked to something as nuanced happening on screen. [26]

Although first and foremost applied to the analysis of sound films, the distinction also holds up for music performed for silent films. Akin to Miceli’s definition, Anderson characterizes the sound-image synchronicity as the tangible attachment of aural changes to visual events, observing that “ideally the music had to catch or ground the physical gestures of the mimes or actors. There were, therefore, many implicit or explicit synch points.” [27]

Naturally, the degree of synchronization and the use of sync points differed depending on whether a score was composed explicitly for a film or whether preexisting music was compiled as film accompaniment. However, in compilation scores, too, music and images corresponded to a remarkable degree—not only at explicit sync points—as the music can establish incidental connections with the image or what Michel Chion would refer to as “synchresis”: “the spontaneous and irresistible weld produced between a particular sound event and a particular visual event when they occur at the same time.” [28] Anderson further highlights the correspondence of musical phrasing with the action and the filmic pace, the matching of a music cue to beginnings and endings of scenes and gestures:

If in what follows we find evidence of stop watches or numbers of seconds being used to coordinate music and image so that music starts when a scene begins and concludes when the scene ends, we have an example of synchronization. If we find evidence of precise timing of music with the initiation and termination of a gesture, we have synchronization. [29]

Such obsessive timekeeping can also be found in the work of Kleiner, who valued precision and accuracy (“you must know [the film] almost frame by frame”) [30] both when composing and compiling. As Anderson concludes in her investigation of the analogies between pantomime music and cinema music, “music was considered essential to both genres, and the similar nature and structure of the two called forth similar solutions.” [31]

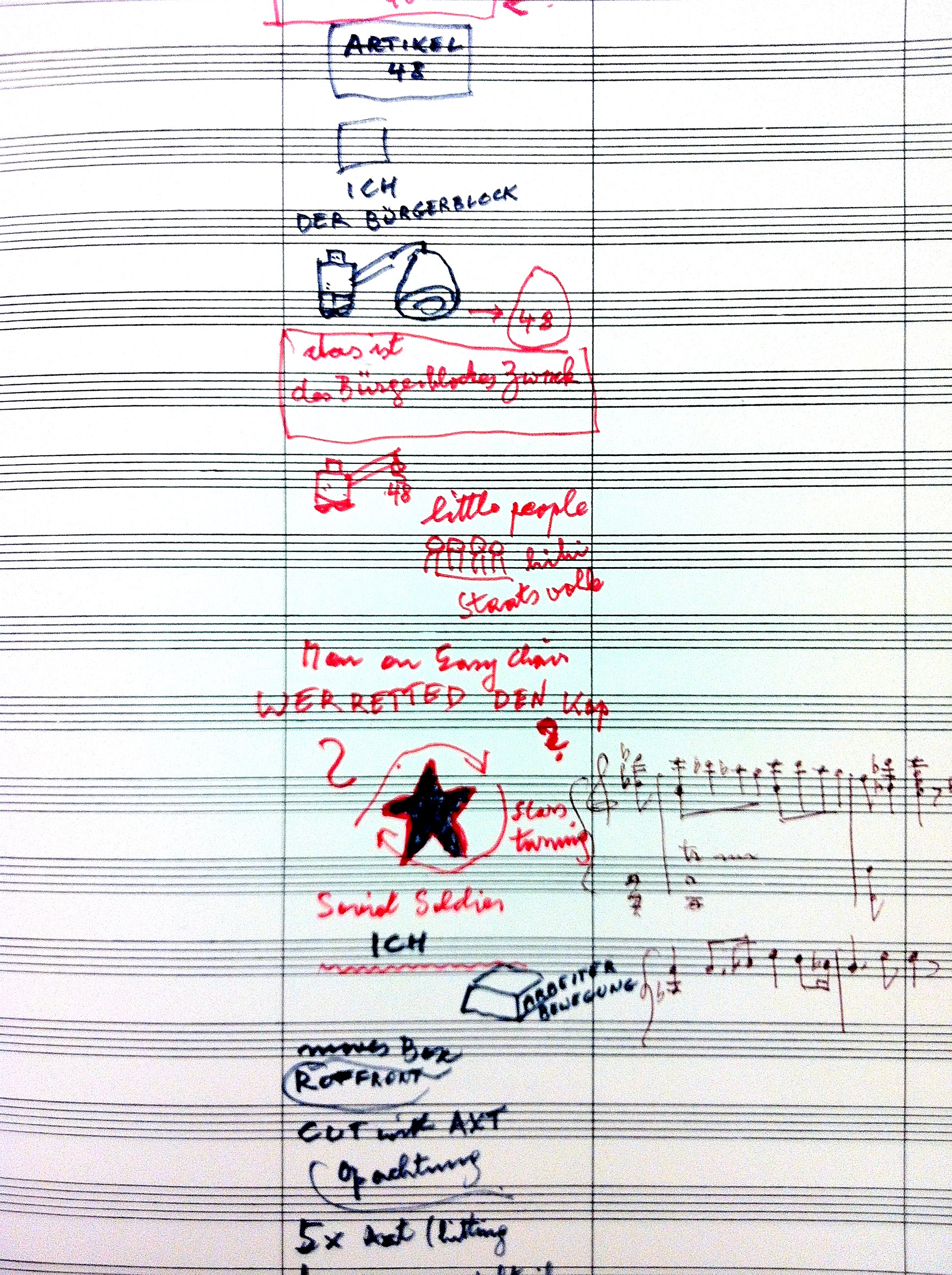

This strong connection between music for dance/pantomime and music for silent films gains significance with regard to Kleiner’s background. Famous dancer and choreographer Agnes De Mille, with whom Kleiner worked in the 1940s through 1950s, considered her art closer to acting and pantomime than classical dance. [32] In a similar vein, the performances of Russian prima ballerina Anna Pavlova (1881–1931) were viewed as “pantomime ballet,” telling stories through movement, gestures, and facial expressions. In ballet and pantomime, music was cued to a dancer’s/actor’s movements. In order to transpose the physical sync points into musical notation, “foot positions instead of notes were put on musical score paper.” [33] It is worth noting that Kleiner regularly used drawings instead of verbal cues to designate sync points in the drafts for his scores (see figure 1). Such drawings might have been merely a shortcut used during a spotting session in order to not have to write out a visual action, but it nonetheless was a practice diffused in dance theater, ballet, and pantomime, representing yet another allusion to the influence of Kleiner’s dance accompanist background on his work. As such, Kleiner was used to observing movements of dancers and to adapt his playing (tempo, rhythm, dynamics) to the live performance on the stage. Knowing much of the music by heart allowed Kleiner to follow performances on stage as well as on the screen with remarkable precision: “Most of it is in my head.” [34]

Fig. 1. Sketch for the score to the short film Dem Deutschen Volke, including visual cues (Arthur Kleiner Collection of Silent Movie Music, Films, DE-DR, Box 5, University of Minnesota Libraries).

It is worth noting that Kleiner’s fondness for dance led to his scoring of some rather unique footage. Douglas Fairbanks’ film material gifted to the Film Library contained a series of dance sequences by famous Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova, allegedly shot by Fairbanks himself during the filming of The Thief of Bagdad, when Pavlova visited the set.

The sequences are charming, but their film quality is ragged and there were no titles or notes on the dances. Kleiner spent weeks tracking down people who’d known Pavlova, personally or professionally, and finally got some of her old souvenir programs from Agnes de Mille. The programs had pictures of Pavlova in costume, which he was able to match with the film sequences to identify the dances, and they also specified the music played. Then, “working like a tailor,” Kleiner cut the music to fit the half-minute sequences, finding the speed of the melodies through Pavlova’s footwork, and timing them together. [35]

Undoubtedly, his long-lasting experiences as accompanist and as composer of stage music aided his proficiency in this kind of detailed synchronizing of music to the images. Kleiner’s reconstruction of the scores to the Pavlova dance films demonstrate the meticulousness with which he approached the scoring process and the locating of historical sources. Four years later, Kleiner wrote, produced, and edited a documentary on Pavlova, which included this very footage. [36]

Another earlier incident shows in a curious way how Kleiner’s work for the stage and the screen overlapped. In 1953, the theatrical company Renaud-Barrault made its American debut in New York City and needed a musical ensemble for a live performance of the iconic pantomime scene from the French epic Children of Paradise ( Les Enfants du Paradis, 1945), starring actor and mime Jean-Louis Barrault. The film had been Kleiner’s favorite movie for years and when asked to accompany the performance on the piano he did not hesitate to say yes. One day after a rehearsal for the pantomime scene, Barrault walked up to Kleiner and said: “I notice you never look at your score when you play for me.” Kleiner responded: “I have seen your film, Children of Paradise so often, I don’t need any score; I know it by heart!” [37]

During his extensive experience as accompanist for dance groups, Kleiner had acquired a set of specific skills that would benefit his future activities in film accompaniment: the ability to concentrate on a (live) performance while playing the piano, a broad knowledge of musical repertories, and a sensibility for (bodily) movement in concurrence with music. This particular artistic background provided a fertile ground for his passion for silent film music.

Kleiner as Musicologist: Historical Sensibility as Leading Concept

As an experienced pianist for modern dance and stage plays, Kleiner might just as well have relied entirely on his broad knowledge of popular and classical repertoire, using improvisation whenever he did not find anything fitting for the silent films he played almost every day. Instead, he sought to recreate a historically sensitive musical accompaniment that reflected the contemporary musical setting of a film. Kevin Donnelly proposes to conceive of present-day approaches to silent film accompaniment as a spectrum flanked by two poles—i.e., historically-accurate versions as opposed to novel, radical ones. Kleiner’s work can be confidently situated on the former side of the spectrum, as he seemingly pioneered the historically-accurate approach:

The “historically-accurate” version retains a traditional character to the score, often guided by knowledge of an “original version.” The approach is scholarly and the processes often follow those of historical research, with the music as an outcome of archival work. These films are often presented at dedicated silent film festivals attended by aficionados and might be seen as film-musical manifestation of museum culture. [38]

Kleiner’s methodological approach at the MoMA was thus very much in line with Barry’s vision of silent film exhibition—that is, a historically informed film accompaniment based on original sources such as scores and cue sheets, and on additional information about the musical accompaniment that could be gleaned from secondary sources such as film reviews, advertisements, and so on. His endeavor to present silent films in a historically sensitive fashion is related to his view of film exhibition as a historical tradition rather than film as a purely aesthetic object. Unlike the purist approach that led to the exhibition of films in complete silence, Kleiner regarded silent film’s performances as objects worthy of reconstruction.

Soon, Kleiner began his search for historical film music material—a search “as frenetic as any of the Keystone chases.” [39] Besides scores and cue sheets by composers and music directors active during the silent period, Kleiner was eager to get his hands on handbooks and manuals for cinema musicians, too, as they featured musical suggestions and other practical instructions. [40] His initial research did not yield as much material as he had hoped. Nevertheless, in 1952 he was rewarded when Paul Norman, a former silent film pianist who had turned to organ and mainly liturgical music once the sound film burst on the scene, introduced himself to Kleiner after attending a silent film screening at the museum. After becoming a regular at the silent film screenings, Norman donated his extensive collection of old scores and cue sheets to the museum; over the subsequent years he substituted for Kleiner whenever he was unavailable. [41] Over the years, Kleiner’s reputation as pianist and silent film music specialist spread, and film producers and directors, who had saved some of their materials, donated scores to the museum’s library.

Kleiner’s musicological perspective and his awareness about the historicity of silent film music had a lasting effect on the way in which this historical practice was perceived as well as on the preservation, restoration, and rediscovery of music used in silent film accompaniment. As musical director of the film library he took on the role of a cultural mediator in which he applied his aesthetic preferences paired with his knowledge of music and film history, thus influencing the silent film music (and film) holdings of the museum. When Kleiner retired, the MoMA’s film library was in possession of “seventy-five to one hundred original scores from silent movies,” owing to Kleiner’s extensive research. [42] Of those, he considered the scores for The King of Kings (1927, Cecil B. DeMille, score by Hugo Riesenfeld and Josiah Zuro), Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1927, Harry A. Pollard, score by Hugo Riesenfeld), Ben Hur (1925, Fred Niblo, rereleased with a score by William Axt and David Mendoza in 1931), and The Iron Horse (1924, John Ford, score by Erno Rapee) to be “of special merit.” [43]

In 1972, Kleiner completed one of his most notable accomplishments, as he claimed: the reconstruction of Edmund Meisel’s original score for Battleship Potemkin (1926, Sergei Eisenstein), a score that had been believed lost during the Nazi invasion of Russia for many years and which Kleiner recalled as “one of the most powerful experiences” of his life when he had witnessed its performance as a young man in Europe. [44] Incidentally, Kleiner’s first original composition for the MoMA in 1940 had been a new score for Potemkin, since Meisel’s original was considered lost at that time. Scoring the Soviet epic was an artistic milestone for Kleiner and even entailed pecuniary benefits. “The score [for Potemkin] was such a hit with the museum that I got a $5 raise,” Kleiner recounts in 1967. [45] For his composition, Kleiner reworked Russian folk themes and used a steady basso ostinato for the famous Odessa steps sequence, not unlike what Meisel had employed for the same scene. [46] Kleiner’s score was used for screenings of Potemkin at the MoMA several times until in 1970 American filmmaker and historian Jay Leyda discovered a complete set of parts of Meisel’s score in the Eisenstein Archive in Leningrad and sent a microfilm copy of the score to Kleiner. With the help of a grant from the National Endowment of the Arts, Kleiner began to restore and arrange the score to fit the film version held by the MoMA at that time, acquired by Barry on a trip to Europe in the 1930s. He recorded the score in 1972 with the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra and it was broadcast the same year on KCET Television as part of their Film Odyssey series. [47] The following years, the film with the restored score was distributed internationally (BBC 2) and shown at various film festivals.

Kleiner’s research concerning the history of silent film music and his quest for original scores were characterized by a distinct musicological drive, as corroborated by his private library, which contains a large number of musicological books, as well as by his broad interest in historical film accompaniment practices. Most significantly, Kleiner had begun drafting a monograph on the development of cinema music—a project that remained unfinished. Yet the volume’s draft and notes reveal Kleiner’s intention of writing a comprehensive history of film accompaniment from mechanical instruments to original scores. Timothy Johnson, librarian at the University of Minnesota and curator of the Arthur Kleiner Collection, [48] confirms this observation: “What you notice with Arthur Kleiner’s music is, he is somebody who is a well-trained musician and knows musicology, music across a number of artists and periods.” [49] This scholarly interest made him consider an original score, such as by Dmitri Shostakovich, Camille Saint-Saëns, or Edmund Meisel, “as interesting and important as the film itself.” [50]

Kleiner as Compiler and Composer: “Paper and a pencil, coffee and cigarettes”

Kleiner oscillated between using original scores or compilation scores based on cue sheets and compiling or composing his own accompaniment. “If I cannot find the score, I try to find music in the style of the time the film deals in. Everything must be historically correct.” [51] If time allowed, he would watch the films in the projection room on the museum’s fourth floor, and jot down the intertitles and actions for each reel working with a stopwatch. “I’d stay up all night in my museum office, using paper and a pencil, coffee and cigarettes. When the museum did its three-month Griffith cycle, that came to 21 sleepless nights.” [52] When time was plentiful, he would take a few weeks for the task but, especially with foreign films which often arrived at the museum a few days before a screening due to shipment delays, he had to work fast. In that case, a film’s first performance, which was usually in the morning when fewer people attended, was a sort of dress rehearsal. The evening screening would go relatively well, and, if the film was held over for some weeks, things would run smoothly. The issue of limited rehearsal time was also a key problem for Kleiner’s colleagues during the silent period. Particularly small and rural venues faced the same difficulties, with the result that they too handled the daily performances in the way Kleiner had—i.e., considering the first performance as a rehearsal. According to the New York Times, Kleiner composed 250 original scores for silent films throughout his life, some of which are preserved at the Library of Congress. In preparation for an upcoming film, Kleiner collected film reviews, mainly by New York Times film critic Mordaunt Hall, which he meticulously pasted into his score books, underlining and circling passages that might impart relevant information for the compilation of the music, such as the film’s period, genre, or geographical setting. This practice recalls what some of Kleiner’s colleagues had done decades earlier, using information about the film in the form of a synopsis supplied by the producer in order to familiarize themselves with the story, especially if there was no opportunity to watch the film before its first public performance.

Kleiner took issue with the overuse and repetition of popular ballads, some of which had become clichés of silent film music. For example, when scoring Griffith’s Home Sweet Home (1914), Kleiner was faced with musical repetition implied by the film images: “The film is only fifty minutes long, but Griffith had some little old man play ‘Home Sweet Home’ on a violin twenty times during that fifty minutes. Do you know what it’s like to write twenty variations on ‘Home Sweet Home’?” [53] In order to avoid ceaseless repeats of the popular song, he used musical variations that evoked the ballad whenever it was clearly indicated in the film images. The delicate balancing of repeating music in a leitmotific sense with variations was a key aesthetic principle in silent film scoring and compilation with which composers sought to create a cohesive musical structure for the score while avoiding tiresome repetition. Naturally, the choices for varying a musical theme were considerably more limited for a pianist compared to a symphony orchestra, so Kleiner had to contend with the means at his disposal—i.e., tempo, pitch, harmonic density, and dynamics.

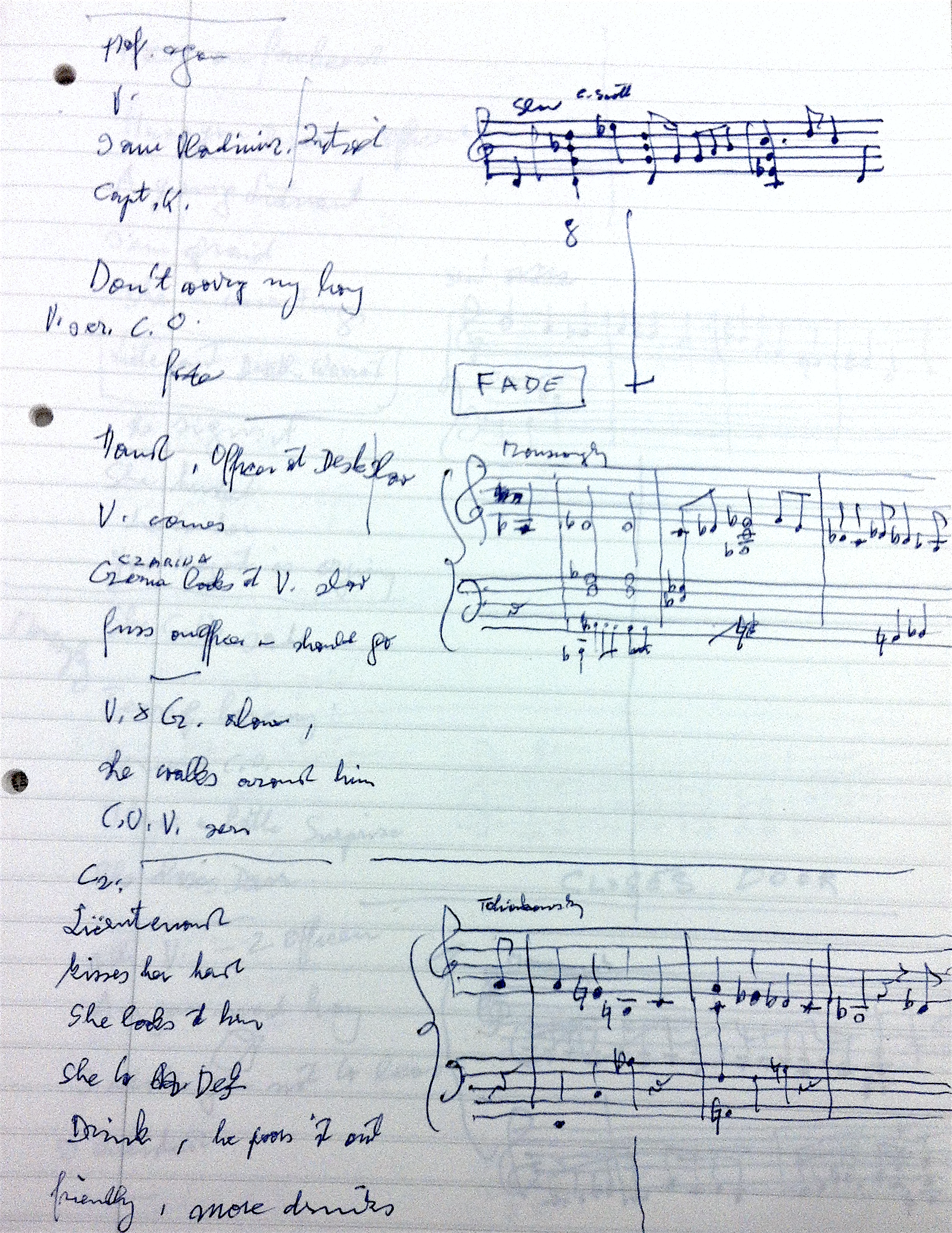

Fig. 2. Spotting session notes for The Eagle (1925) including music incipits (Arthur Kleiner Collection of Silent Movie Music, Films, EA-FI, Box 6, University of Minnesota Libraries).

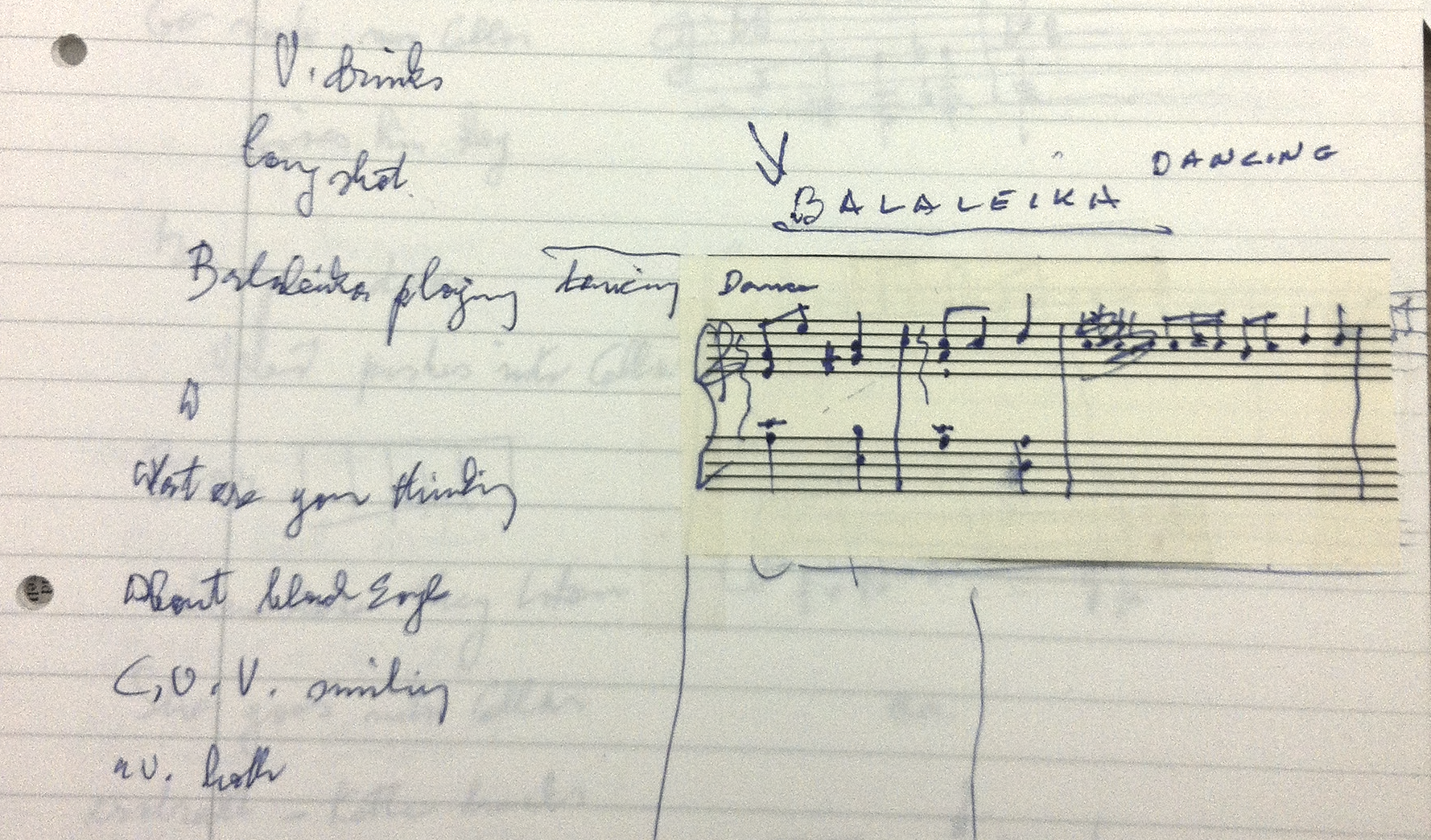

The sketchbooks preserved at the Arthur Kleiner Collection provide scholars with compelling information about Kleiner’s creative process, comprising detailed synopses that include a film’s plot details, exits, entrances, key images, and dialogue titles. Generally written on music paper, verbal or visual cues were jotted down in one column, while music titles or fragments were noted to the side(s) (see figure 2). These scribbled music incipits acted as mnemonic devices and contained excerpts from preexisting music as well as Kleiner’s own compositions. On these synopses, for which he occasionally used his mother tongue (especially for German film productions), Kleiner also highlighted diegetic sounds and onscreen performances, such as dancing, singing, or a band playing. Films containing musical performances provided further information for Kleiner, functioning as “embedded cue sheets.” [54] In his accompaniment, he would pay special attention to these on-screen musical performance scenes and aim for the music to coincide with the start (and end) of the filmed musical performance, as discussed above with regard to synchronization. For example, in his notes for the film The Eagle (1925, Clarence Brown), based on the novel Dubrovsky by Alexander Pushkin and taking place in the Russian army during the late eighteenth century, Kleiner scribbled a brief music incipit to correspond with the scene depicting a Balalaika band and an ensuing folk dance scene (see figure 3). In the same accompaniment, he inserted another music incipit entitled “Zorro”; undoubtedly a reference to the Douglas Fairbanks swashbuckler The Mark of Zorro from 1920. Kleiner cued this melodic fragment (a short ascending chromatic line with semitones; enough to evoke what would have been categorized as “sinister” or “foreboding” in 1920s cinema music libraries) at the first appearance of Rudolph Valentino as “The Black Eagle,” a masked Robin Hood-like character which did not exist in the original novel and was instead inspired by Fairbanks’s “Zorro.”

Fig. 3. Notes with incipit for Balaleika dance number in the 1925 film The Eagle (Arthur Kleiner Collection of Silent Movie Music, Films, EA-FI, Box 6, University of Minnesota Libraries).

Kleiner as Performer: “Unnoticed but Noteworthy”

“Are you primarily a musician?”

“Yes.”

“Who by bad luck got into movies?”

“That’s right!” [Kleiner laughs]

[55]

(Arthur Kleiner and Bronisław Kaper, 1975)

Kleiner’s passion for original scores by established composers might have been partly responsible for his loyalty to his occupation as silent film pianist, as he hinted in an interview at the Berlinale in 1979:

I really became interested when I discovered that many great composers had written scores for silent films. Did you know that Saint-Saëns wrote one as early as 1908? Or Richard Strauss the music for the “silent” version of Der Rosenkavalier? In fact, some of them played for silent movies when they were young: Shostakovich did it in Russia to earn extra money before he wrote his first symphony. [56]

It is these and similar comments by Kleiner––some of which have to be read between the lines, while he is much more explicit in others––that stirred my interested in his personal attitude towards his occupation and in the way in which he reconciled his own artistic ambitions with his public persona. Despite a certain admiration among film aficionados and silent film buffs, being a silent film pianist was hardly well regarded at the time by serious composers whom Kleiner considered his peers. The subtext of some of Kleiner’s comments conveys his concern for being demoted to movie music, even worse, film accompaniment, where he usually performed other people’s compositions.

In a series of writings stemming from a seminal 2006 article, Philip Auslander has articulated the notion that musicians enact personae in their performances: “What musicians perform first and foremost is not music, but their own identities as musicians, their musical personae.” [57] In the case of Kleiner, it is particularly useful to stretch the definition of performance to include any public appearance and representation; in other words, as Auslander also suggests, a musician’s performance does not finish with the last note she sang or played on her instrument, but “to be a musician is to perform an identity in a social realm that is defined in relation to the realm.” [58] Auslander’s performer-centered concept of the musical persona offers a useful framework for interpreting Kleiner’s self-perception as an artist, both while performing music as well as in public appearances such as interviews and other (print and video) footage. In turn, Kleiner’s “performance” of the social identity of a silent film pianist (active during the sound era), drawing on a specific image of high culture, has shaped public understanding of silent film sound through the sophistication and cultural air that Kleiner personified through his mediatized public presence.

Leaning on Erving Goffman’s sociological perspective regarding the concept of self-presentation, Auslander borrows the term “front” to delineate “the means a performer uses to foster an impression.” [59] Dividing this notion further in “personal front” (manner and appearance) and “setting” (the physical performance context), these means include “the expressive equipment of a standard kind intentionally or unwittingly employed by the individual during his performance.” [60] The setting of Kleiner’s type of performance as a silent film pianist comes with predefined conventions for both the audience and the performer. The pianist is sat at a piano in front of the screen in a darkened movie theater, sometimes on a stage, other times in an orchestra pit. The screening of a silent film is not centered on the musical performance as such. Albeit live music has a certain allure, particularly for today’s audiences, the music nevertheless recedes into the background during the screening experience due to the narrative absorption of the audience into the film. And while Kleiner’s contribution was without doubt crucial to a film’s successful showing, his music was usually not at the center of attention during the actual performance. [61] From a performer’s perspective, the darkened physical space and the connotation of providing “only background music,” to use hyperbole, did not align with some of Kleiner’s previous performance contexts in which he was viewed more as a classical musician and as belonging to a stage ensemble.

Kleiner’s “personal front” is even more intriguing when viewed through the lens of the concept of musical persona. In this regard, his early socialization is crucial for understanding some of his mannerisms and characteristics. For example, he never lost his strong Austrian accent when speaking English, although, as his son Erik Kleiner affirmed, he did not speak German at home either. [62] Described as an “extremely soft-spoken, polite and precise gentleman” by the New York Times, [63] his way of dressing, speaking, and performing conveyed a highly formal and exclusive attitude, to the point that some of his behaviors and even his attire were at odds with his social surroundings later in life, as his son confirms:

You know, he wasn’t your standard dad, growing up in Minneapolis or Hopkins. Dads were taking their kids to the ballgame, and my dad was in his black raincoat with his hat, going to the University to play the piano. He didn’t drive, he took the bus. He never had his license. … He was a different kind of dad… and he was older, too. [64]

Another interviewer stressed Kleiner’s apparent unobtrusiveness:

His name means “little one.” He presents the sort of appearance that causes receptionists to look up after several oblivious moments and murmur in embarrassment, “Oh, I’m sorry, I didn’t see you standing there.” He speaks in an undertone rendered even softer by the gentle sibilance of a Viennese accent. [65]

Fig. 4. Kleiner, wearing a bowtie, at the recording session for Battleship Potemkin in 1972. From the private collection of Erik Kleiner.

A curious fashion artifact stands out when sorting through photographs of Kleiner: he often wore a bowtie when performing or attending official events (see figure 4). The bow tie, a fashion accessory reminiscent of the Wiener Klassik (the First Viennese School) style, as well as of classical musicianship, might have served as a commemorative “tie” to his native land and to his artistic home as a musician.

In 1966, one year before retiring from MoMA at age 63, Kleiner gave a particularly revealing interview regarding his transfer from Europe to the United States, in which he implicitly addressed the perceived superiority of “absolute” or concert hall music over the musical accompaniment of silent films as “functional music,” a notion Kleiner grappled with throughout his life and career. The interview was conducted by Gretchen Weinberg for the magazine Film Culture, a publication whose target audience would have been familiar with avant-garde cultural trends (both cinematic and musical). Kleiner’s awareness of such specific readership potentially shaped his choices about what to disclose and in which way. The article was published in the form of a monologue in the regular column “The Backroom Boys.” Weinberg opened her article with the preamble: “The first part of a series featuring interviews with individuals whose place in the history of film is often unnoticed but in many cases is noteworthy.” [66] In the article, Kleiner contemplates his career choices, expressing an equivocal view about committing as thoroughly to silent film music as he had done.

“There is so much I wanted to do here [at the MoMA]… hold concerts for full

orchestra of some of the film scores … Mortimer Wilson’s scores for Douglas

Fairbanks’ The Thief Of Baghdad and The Black Pirate are

wonderful; he was a pupil of Max Reger, the German composer, Wilson; a real

musician, not like so many others … but there’s no time for that, they tell

me … a concert like that’s very expensive … it needs rehearsals … it’s an

unrealized dream. .. I have only unrealized dreams … Schönberg’s

Film-Music, Erik Satie’s for René Clair’s Entr’acte, Saint-Saëns’

for The Assassination Of The Duc De Guise. Darius Milhaud’s music

to accompany a Charlie Chaplin film and for Renoir’s The Little Match-Girl, Richard Strauss’ Music for an Imaginary

Movie. …

I don’t know much about films … but I think it’s an art, too … it’s sort of

a sad reputation, don’t you think? Musical accompanist … I wasn’t always

one, you know, I used to compose … but the composing I do for the films

here, it’s so unimportant, actually … I only do it if I can’t find music;

then I have to, if there’s no other way out … the Museum audiences only

notice if you miss a cue or play it wrong, and sometimes not even then …

they don’t really listen … I’d like to be known as a composer, I think, I

don’t know … maybe the composing I used to do … it’s only good if you

compose with inspiration, an opera or symphony or sonata … but playing for

the films … like a stock music library in Hollywood … it’s measured, like

you measure cloth for a dress … or like a train conductor whistle-stops for

the different stations: at 3:04, you have to be in a certain station at a

certain time, on cue … and so it goes … not really, but almost… like a trip

… to nowhere …”

[67]

Kleiner’s poignant admissions touch the core of his personal struggles regarding his life and career choices. The foregrounding of his classical music education and the reference to his most revered composers show a desire for a highbrow artistic lineage and an alignment with the cultural sphere associated with his native Vienna at the time. Having identified some aspects of Kleiner’s self-image as a performer and as a representative of a particular musical heritage, the following analysis of a documentary written by Kleiner will offer an interpretation of how these aspects of his musical persona manifested in his work.

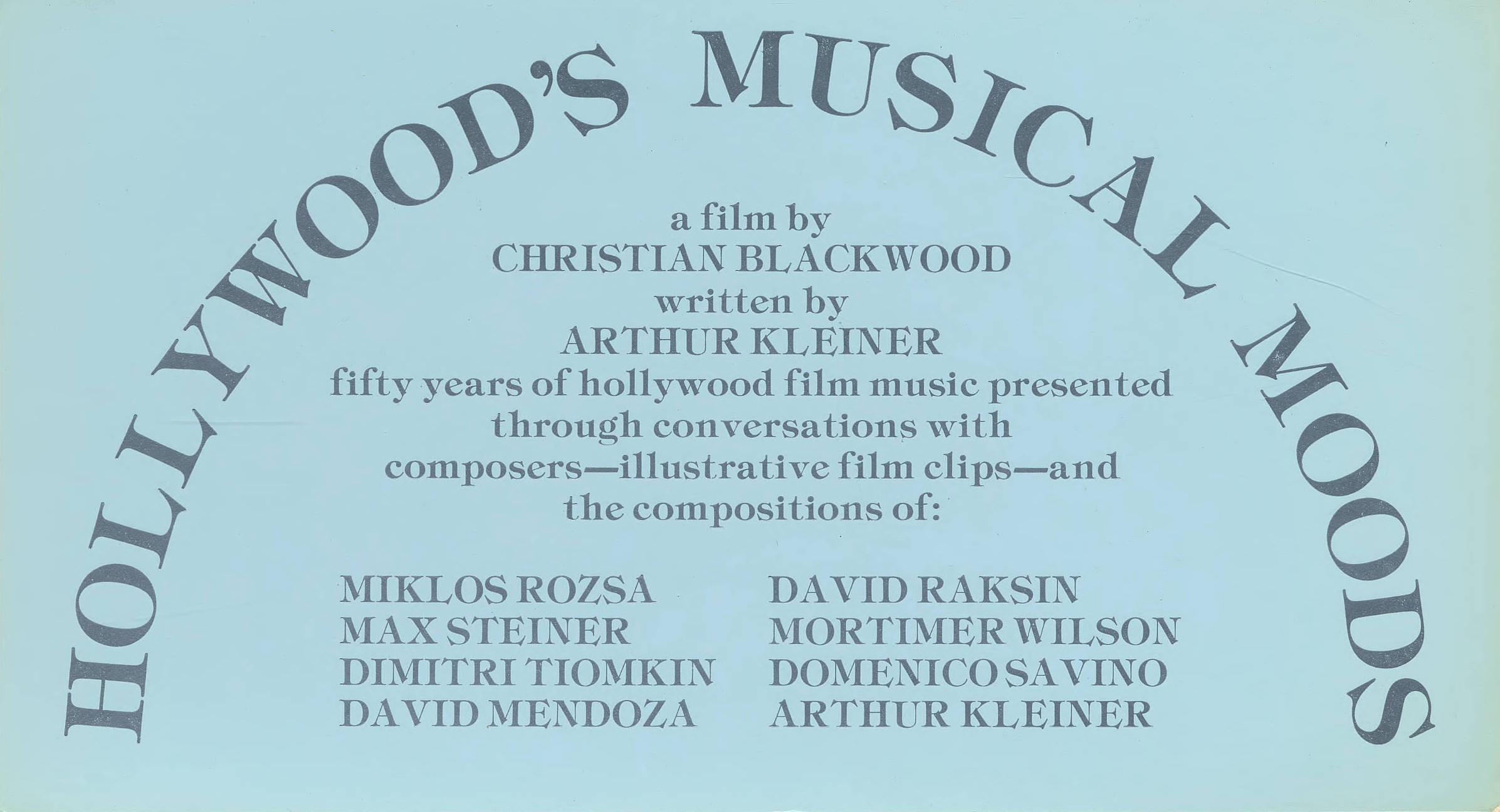

Sophistication by Association – Hollywood’s Musical Moods (1973)

In the years before leaving New York City, Kleiner worked as pianist for television (NBC, CBS, ABC) on a freelance basis, and was involved with the documentary genre through his work on Anna Pavlova among others. In 1972/73, he wrote and presented the documentary Hollywood’s Musical Moods, an hour-long portrayal of the film composers from Hollywood’s “Golden Age” in the 1930s to the 1950s in which Kleiner narrates and plays film music excerpts on the piano as he interviews David Raksin, Max Steiner, Dimitri Tiomkin, Miklós Rózsa, and Domenico Savino. [68] Dissecting Kleiner’s role in the genesis of this film reveals different layers of how he dealt with this topic as a historian, filmmaker, and classically trained musician. It also sheds light on the personal ambition that might have inspired this project. An advertisement for the documentary alludes to how Kleiner would have liked to be perceived: en par with composers such as Steiner, Raksin, and Tiomkin, who to this day embody the foundational creators of the classical Hollywood sound (see figure 5). [69]

Fig. 5. Postcard advertising Hollywood’s Musical Moods (Arthur Kleiner Collection of Silent Movie Music, University of Minnesota Libraries).

The material preserved at the AKC contains a six-page document that appears to be an early draft of the script for Hollywood’s Musical Moods, which allows us to trace and compare two stages in the development of this documentary. Kleiner’s script is entitled “History of American Film Music. 1889–1952. Second draft” and dated January 1972. [70] The differences between this draft and the final film are significant and revealing. In short, Kleiner’s original idea was to foreground film music’s early connection to musical modernism as well as the existence of original silent film scores by notable composers. In the intended opening scene, composers Virgil Thomson, Aaron Copland, and Kleiner would be seen watching Ballet Mécanique, the well-known 1924 Dadaist art film co-directed by Fernand Léger and Dudley Murphy, while listening to George Antheil’s “pianola roll[s]” by the same name played by Thomson himself. [71] The script reads on: “Would this picture loose its continuity without any music? It certainly would,” and proceeds demonstrating this argument by showing the film without music, only to conclude: “Musical background was used from the very beginning. Movies were never performed in silence.”

Let us linger on this scenario for a moment. We have silent film pianist Arthur Kleiner with two key figures of American modern music who also worked in film sitting in Thomson’s apartment (as per Kleiner’s script). Their subject of discussion is the now well-regarded concert piece Ballet Mécanique by Antheil, whom Kleiner had known as a young man in Vienna. The idea of using this specific example bears a certain irony, as this is precisely an instance of film and music eventually not ending up together. It is important to note that although Antheil’s Ballet Mécanique was supposed to accompany the 1924 namesake film, the filmmakers and the composer dropped the idea during the production process. When completed, the film had a running time of nineteen minutes, while the music piece was about ten minutes longer. The first public premiere of Ballet Mécanique in Paris in June 1926 turned into a contentious concert, and the piece became one of the hallmarks of musical modernism. Kleiner’s choice of starting a documentary about film music history with this constellation of people discussing avant-garde music and film—and above all with a piece that, despite the original intentions, is technically not film music—is curious but not surprising. It is instead very much in line with his understanding of film music as a sophisticated, artistic medium of high cultural status, which is precisely what Ballet Mécanique represented. Besides reflecting Kleiner’s personal musical preferences, the setting echoes Kleiner’s affinity with an aesthetic tradition and cultural lineage that leaned heavily on European roots (Copland, Thomson, and Antheil studied and worked in Europe, mainly in Paris) while establishing a strong connection to modern music. Moreover, Kleiner intended to interview both Copland and Thomson about their work in documentary film scoring— not exactly a mainstream genre in American film history.

Kleiner’s vision of embedding his narration about the development of film music within American musical modernism did not materialize. Instead, Hollywood’s Musical Moods starts with a scene from the Douglas Fairbanks picture The Black Pirate (1926, Albert Parker) with the original score by Mortimer Wilson played by Kleiner on the piano. Deprived of his intended opening, Kleiner tried to “balance” the images of a Hollywood swashbuckler adventure by pointing out that Wilson “studied composition under Max Reger and has written five symphonies, conducted major orchestras including the New York Philharmonic,” thus instilling a concert (i.e., serious) music affiliation. [72]

The final page of the draft contains a section entitled “Hollywood Film Composers. (Not confirmed yet),” listing Max Steiner, Franz Waxman, and Dimitri Tiomkin as potential candidates for interviews. Eventually, the documentary featured interviews with Raksin, Tiomkin, Rózsa, and Savino conducted by Kleiner in person and with Steiner via phone. The film clips discussed include scenes from Spellbound (1945, Alfred Hitchcock), Laura (1944, Otto Preminger), and High Noon (1952, Fred Zinnemann) inserted in the interviews with the respective composers. It is possible that at an early stage of developing the script, Kleiner was not yet certain whether he would be able to interview Hollywood’s most celebrated film composers. When the planned interviews were confirmed during the production process, he substituted the intended segments with Thomson and Copland with conversations with Raksin, Waxmann, Steiner, and consorts. [73]

In the interviews Kleiner conducted with film music composers in preparation for the documentary as well as for his book project, he frequently referred to “serious” composers like Arnold Schönberg, Paul Hindemith, or Franz Schreker, as well as music critics Eduard Hanslick and Julius Korngold, injecting his own competences in music history, analysis, and theory into the dialogues with his peers. [74] For example, with Hugo Friedhofer, Kleiner discusses twelve-tone technique, serial music, and twentieth-century atonal compositions. Coming from a social sphere in which music was highly codified to emphasize class differences, and in which rigid distinctions between light music ( Unterhaltungsmusik) and art music (Kunstmusik) divided film music composers from their opera and concert hall composer colleagues, Kleiner insisted on highlighting the renowned figures of music history who contributed to silent film music. One of the guiding principles in his various roles was to emphasize the ties between silent film music and so-called “serious” composers. It is not difficult to imagine that at times Kleiner felt underrated as a musician and artist, working in a musical métier that was (and still is, to some extent) largely associated with a limited repertoire of staple pieces of popular music, which is why he tried to distance himself so vehemently from certain clichés such as “ragtime music” or popular ballads (he referred to the song “Hearts and Flowers” as “a perfectly dreadful piece”) and everything these numbers stood for in connection with silent film music. [75]

Although successful composers of film music were well regarded in their own circles, film music was still struggling for recognition and acceptance in the art music world and within academia during Kleiner’s lifetime. Thus, an underlying aim of Kleiner’s documentary could have been an effort to inscribe his own work in silent film music into the broader history of film music, which was emerging as an academic discipline during the late 1970s and 1980s. Having composed music for ballet and stage plays, and having worked with major personalities in those realms, Kleiner might have dreaded the thought of his legacy to be judged solely by his piano playing in a darkened room, and thus sought to legitimize his status as a professional musician and composer.

Less than two months after his final trip to Europe in early 1980, Arthur Kleiner died of a heart attack after battling cancer at the age of 77 in his home in Hopkins, Minnesota. Two weeks earlier, he had performed at a large silent film exhibition at the Walker Center of the Arts in Minneapolis, where he played his original score for The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928, Carl Theodor Dreyer), and a score to Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927), in the presence of the French director. After the event, 90-year-old Abel Gance handed Kleiner a handwritten note in which he personally thanked Kleiner and acknowledged his skill on the piano.

His self-doubts aside, Kleiner was responsible for helping shape the image and reputation of silent cinema and film accompaniment in many people’s eyes for generations. His activities at the MoMA, at international film festivals and workshops, in university classrooms, and at the Walker Arts Center in Minneapolis kept the art of silent film accompaniment alive for decades after the last mute images had lit up screens in Western commercial cinemas in the early 1930s. In his various significant roles—as a historian, a composer/compiler, and as a performer—he was influenced by his cultural background and sensibilities, by his desire for an affiliation with Europe’s cultural and musical heritage, as well as by his affinities for musical modernism. His persistent emphasizing of the links between silent film music and serious composers, by invoking original film scores by established artists, is to be seen in a similar vein as the original draft for his documentary, in that he was looking to elevate his field of occupation by associating it with a prestigious musical tradition that centered around the composer as the author of a work of art. In this sense, his efforts at reconstructing and preserving historical silent film scores by renowned composer can be viewed as efforts at self-preservation for an artist who had too many “unrealized dreams.”

* Research for this article at the Arthur Kleiner Movie Music Collection at the University of Minnesota was funded by the Botstiber Foundation, which I thank for their kind support. I am grateful to Timothy Johnson and Cheryll Fong for their kind hospitality when I visited the collection. I sincerely thank Erik and Ann Kleiner for taking the time to correspond and meet with me, and for sharing not only documents and photos but also memories of their father (in law) Arthur Kleiner. Finally, I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers of my article for their insightful comments which greatly helped me develop my argument and the article overall.

[1] The Museum of Modern Art, “Arthur Kleiner, who has been composing, arranging and playing the piano accompaniments for silent films at The Museum for 28 years to retire,” press release, March 28, 1967.

[2] Ann-Kristin Wallengren and Kevin J. Donnelly, “Music and the Resurfacing of Silent Film: A General Introduction”, in Today’s Sounds for Yesterday’s Films: Making Music for Silent Cinema , ed. Kevin J. Donnelly and Ann-Kristin Wallengren (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 1.

[3] See Peter Decherney, Hollywood and the Culture Elite: How the Movies Became American (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 6.

[4] Decherney, 8.

[5] Steven Higgins, Still Moving: The Film and Media Collections of the Museum of Modern Art (New

York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2006), 8.

[6] The Museum of Modern Art, “Initial Showing of First Program of Motion Pictures,” press release, January 4, 1936.

[7] The Museum of Modern Art, “Theme Music for Movies Being Written by Music Dept. of Film Library,” press release, February 13, 1936, .

[8] Decherney, Hollywood and the Culture Elite, 199.

[9] P. Adams Sitney, The Essential Cinema (New York: Anthology Film Archives and New York University Press, 1975), vii.

[10] Vachel Lindsay, The Art of the Moving Picture (New York: Macmillan, 1915), 197.

[11] Eszter Kondor, Aufbrechen. Die Gründung des Österreichischen Filmmuseums (Wien: Österreichisches Filmmuseum – Synema, 2014), 130. Translation by the author.

[12] Kondor, 130.

[13] Mary Ann Doane, “The Voice in the Cinema: The Articulation of Body and Space,” Yale French Studies 60 (1980): 33.

[14] Ronald S. Magliozzi and Charles L. Turner, “Witnessing the Development of Independent Film Culture in New York: An Interview with Charles L. Turner,” Film History 12, no. 1 (2000): 78.

[15] Interview by Arthur Kleiner with Hugo Friedhofer, Cassette label: Aug 12, 1974, Hugo Friedhofer in his home. Preserved at the Arthur Kleiner Collection of Silent Movie Music (hereafter AKC), Special Collections and Rare Books, Elmer L. Andersen Library, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

[16] Gretchen Weinberg, “The Backroom Boys,” Film Culture 41, Summer (1966): 84. Between 1925 and 1938, Kleiner was the accompanist (organ, piano, harpsichord) and composer for a number of dance companies and solo dancers. He played for Valeria Kratina and Rosalia Chladek of the Hellerau-Laxenburg dance school on their tours in Sweden, Estonia, and Latvia. Other famous collaborators were Marta Wiesenthal (sister of Austrian dancer Grete Wiesenthal) as well as Claire Bauroff, who was chiefly known for her artistic nude dance performances and her support of the nudism movement.

[17] Weinberg, “The Backroom Boys,” 84.

[18] Alan M. Kreigsman, “A Forte Virtuoso Hides Behind a Pianissimo Image,” Washington Post, January 25, 1970.

[19] Decherney, Hollywood and the Culture Elite, 138.

[20] The Museum of Modern Art, “Arthur Kleiner, who has been composing, arranging and playing the piano accompaniments for silent films at The Museum for 28 years to retire,” press release, March, 28, 1967.

[21] Bernard Krisher, “Pianist in the Dark,” New York Herald Tribune, April 24, 1955.

[22] For a compelling argument about synchronized music in the silent period, see Gillian B. Anderson, “Synchronized Music: The Influence of Pantomime on Moving Pictures,” Music and the Moving Image 8, no. 3 (2015): 3–39.

[23] See Carlo Piccardi, “Pierrot al cinema. Il denominatore musicale dalla pantomima al film,” Civiltà musicale 19, no. 51/52 (2004): 35–139.

[24] Anderson, “Synchronized Music,” 4.

[25] Anderson, 4. Emphasis mine.

[26] Sergio Miceli “Leone, Morricone and the Italian Way to Revisionist Westerns”, in The Cambridge Companion to Film Music, ed. Mervyn Cooke and Fiona Ford (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 290.

[27] Anderson, 18.

[28] Michel Chion, Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen, 2nd ed., trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 64.

[29] Anderson, 4.

[30] “Composer Becomes Piano Player For Museum’s Old-Time Movies”, New York Times, September 17, 1952.

[31] Anderson, 19.

[32] See Judy L. Hasday, Agnes de Mille (Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2004), 66–67.

[33] Anderson, 16.

[34] Kreigsman, “A Forte Virtuoso.”

[35] Joanne Stang, “Making Music – Silent Style,” New York Times Magazine, October 23, 1960: 83–86, at 84–86.

[36] In 1964 Kleiner wrote, produced and scored a film about the dancer, supported by the MoMA. The 20-minute documentary Anna Pavlova is preserved at the Library of Congress. Kleiner was also working on a documentary about Russian dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, but it was never realized.

[37] Weinberg, “The Backroom Boys,” 86.

[38] Kevin J. Donnelly, “How Far Can Too Far Go? Radical Approaches to Silent Film Music,” in Donnelly and Wallengren, Today’s Sounds for Yesterday’s Films, 13. Emphasis mine.

[39] Stang, “Making Music,” 83.

[40] Thematic music cue sheets were widespread devices of musical suggestions during the silent film era since the mid-1910s, peaking in the 1920s. Cue sheets were usually compiled by composers or arrangers on behalf of music publishers and sometimes commissioned by film producers. A typical cue sheet contained a numbered list of music suggestions (cues) timed to aid in the synchronization of music to a specific film.

[41] “Composer Becomes Piano Player.”

[42] The Museum of Modern Art, “Charles Hofmann to Lecture on Musical Accompaniment to Silent Films,” press release, January 23, 1970.

[43] Arthur Kleiner, “New Yorker Arthur Kleiner writes about Film Scores,” Sight and Sound 13, no. 52 (1945): 103–4.

[44] John Rockwell, “Search for ‘Potemkin’ Lost Score,” Los Angeles Times, March 23, 1972.

[45] Howard Thompson, “Museum Losing Sound of Silents,” New York Times, March 25, 1967.

[46] “Meisel made use of a percussive ostinato, barbaric and unstoppable in its strut, as an acoustic correspondence to the murderous squad of Cossacks in the massacre scene.” Francesco Finocchiaro, “Sergei Eisenstein and the Music of Landscape: The ‘Mists’ of Potemkin between Metaphor and Illustration,” in The Sounds of Silent Films: New Perspectives on History, Theory and Practice , ed. Claus Tieber and Anna K. Windisch (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 185.

[47] Kleiner copyrighted the conductor’s score (“revised and edited by Kleiner”) in August 1971.

[48] One year after his death in 1980, Kleiner’s wife Lorraine Kleiner donated his extensive library of music scores (printed scores and manuscripts for nearly 700 silent films), sheet music, books, tapes, broadcasts, and other material to the University of Minnesota, where it is now preserved in the AKC. Much of the material is digitized and forms a rich source for silent film history and music research.

[49] Timothy Johnson, interviewed by Susan Gray, “Kleiner Silent Film Music Collection,” PRX, uploaded on August 2010.

[50] “Composer Becomes Piano Player.”

[51] Weinberg, “The Backroom Boys,” 86.

[52] Thompson, “Museum Losing Sound of Silents.”

[53] Stang, “Making Music,” 83.

[54] When studied carefully it becomes clear that silent films reveal a variety of implied musical cues in the form of filmed music performances, inserts of sheet music, songs mentioned in intertitles and more, which again points to the idea that synchronization was not an afterthought during the silent era, but a concern of filmmakers as well. See Claus Tieber, “Filme als Cue Sheets: Musikfilme, Kinomusik und diegetische Musik, Wien 1908–1918,” Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung 9 (2013): 26–45.

[55] Interview with Bronisław Kaper, July 23, 1974, Beverly Hills, 02:25, Kleiner_C002_Kaper_Side1, AKC.

[56] “Accompanist Extraordinary”, berlinale-tip, March 3, 1979, 12.

[57] Philip Auslander, “Musical Personae,” TDR/ The Drama Review 50, no. 1 (2006): 102. See also his “‘Musical Personae’ Revisited,” inInvestigating Musical Performance: Theoretical Models and Intersections, ed. Gianmario Borio, Giovanni Giuriati, Alessandro Cecchi, and Marco Lutzu (London: Routledge, 2020), 41–55, and In Concert: Performing Musical Persona (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021), chap. 5 “Musical Personae,” 87–128.

[58] Auslander, In Concert, 88.

[59] Auslander, In Concert, 100.

[60] Auslander, In Concert, 100–101, quoting Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (New York: Doubleday, 1959), 22.

[61] I would argue that this particular state of audience reception is debatable for some present-day screenings of silent films, especially when the musical accompaniment is rendered by a well-known music ensemble (e.g. Alloy Orchestra) or a symphony orchestra. At these events, the musical accompaniment seems to retain or continually regain the audience’s attention during the screening and the musicians remain a very visible and central focus of the live performance.

[62] I had the chance to interview Erik and Ann Kleiner during my research visit at the University of Minnesota in 2015. The interview was held at an off-campus coffee shop on March 22, 2015.

[63] Stang, “Making Music.”

[64] Erik Kleiner, author interview.

[65] Kreigsman, “A Forte Virtuoso.”

[66] Weinberg, “The Backroom Boys,” 83. Emphasis mine.

[67] Weinberg, 86–87.

[68] Hollywood’s Musical Moods , directed by Christian Blackwood (Michael Blackwood Productions, 1972).

[69] Budget constraints during production were cited as the reason for omitting the work by Erich W. Korngold in the film, as clips from the films he scored would have been too expensive to include. See William K. Everson, “A Description of Hollywood's Musical Moods by The New School,” July 16, 1975, AKC.

[70] Arthur Kleiner, “History of American Film Music,” script, second draft, January 1972, AKC.

[71] Kleiner, “History of American Film Music,” 1.

[72] Hollywood’s Musical Moods , at 00:01:56 – 00:02:09.

[73] It is difficult to determine the extent to which the documentary was actually distributed. It was presented at the summer festival of the New School in New York City in 1975, was shown at several film festivals over the years, and was probably most recently screened at a film workshop in Katoomba, Australia, in 2013.

[74] Tapes of these interviews are now part of the AKC.

[75] Stang, “Making Music.”