ARTICLE

Callas and the Hologram: A Live Concert with a Dead Diva *

João Pedro Cachopo

Sound Stage Screen, Vol. 2, Issue 1 (Spring 2022), pp. 5–29, ISSN 2784-8949. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. © 2022 João Pedro Cachopo. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54103/sss18310.

Writing about Callas in Concert during the COVID-19 pandemic brings with it a strange feeling. Premiered in 2018, the show employs holographic digital and laser technology to bring the legendary diva back to the stage almost 50 years after her death. It is a technically and artistically savvy spectacle that reflects the spirit of the times with a tinge of nostalgia. At the same time, as so many other live shows, especially those that are meant to go on tour, Callas in Concert was severely impacted by the pandemic and its restrictions. Lockdowns, quarantines, and curfews, leading to a wave of cancelations, brought the project’s career to a standstill.

Due to the phantom-like apparition of Callas, the show itself—which I had the opportunity to attend in Barcelona on November 7, 2019—is already somewhat uncanny. But the present circumstances provide an additional layer of strangeness to my memory of it. The experience feels distant, but also—thanks to the technological complexity of the concert—strangely familiar. To recognize the intersection of these two layers of unease is crucial for understanding the purpose of this article. In fact, while examining this recent instance of the Callas myth, my aim is to understand what it tells us about the present situation of opera, in a moment when it becomes apparent that the pandemic has not only accelerated but also revealed changes that were already underway over the past two decades. [1]

I decided to focus on this show for still another reason. Maria Callas, it should not be forgotten, is not only opera’s prototypical diva, but also a dead singer whose cult has outlived her and, in some ways, even intensified in recent years. For this reason, Callas in Concert—a show in which the artist resurrects from the spirit of technology, as it were—provides an invaluable opportunity to examine how closely the interplay of opera and new media has evolved against the backdrop of latent anxieties about the alleged death of opera. It is this mixture of technological and artistic innovation, on the one hand, and recurrent concerns about opera’s survival in a media-saturated culture, on the other hand, that I try to disentangle in this article.

Callas in Concert was launched by BASE Hologram in 2018. [2] A branch of BASE Entertainment, the new live entertainment company aims to introduce “a revolutionary new form of live entertainment artistry that fuses extraordinary theatrical stagecraft with innovative digital and laser technology to bring true music legends back to the global stage in a state-of-the-art hologram infused theatrical experience.” [3] Four shows have been presented so far:In Dreams: Roy Orbison in Concert (2018), Callas in Concert (2018), Roy Orbison & Buddy Holly: The Rock ‘n’ Roll Dream Tour (2019), and An Evening with Whitney [Houston] (2020). In 2019, the company was also working on a hologram of Amy Winehouse, but the show did not see the light of day. [4]

One thing is certain, Maria Callas is not alone in providing the inspiration for these multimedia adventures where the so-called great divide between high art and popular culture seems to have very little relevance. In fact, it is significant that almost four decades after the heyday of the postmodern debate, these holographic shows have been equally successful regardless of whether the performer being emulated is a pop singer or an operatic soprano. This gives us a hint as to what the fans of Whitney Houston and Maria Callas might have in common—i.e., not only a fascination with the unique voices and charismatic presence of the two singers, but also a penchant to fall for the thrill of attending a live concert with a dead singer. Apparently, the blurring of the divide between high art and popular culture, which Andreas Huyssen celebrated in the 1980s, did not immediately entail the undermining of the ideological assumptions—namely those associated with the values of uniqueness, charisma, and authenticity—on which the edifice of high art stood. [5] On the contrary such values seem to persist in the imagination of audiences and practitioners, albeit in updated or disguised forms.

Similarly to other BASE hologram projects, Callas in Concert proposes a two-in-one experience in which “liveness” and “mediatization” are indelibly intertwined. Their relation, as Philip Auslander convincingly explains in seminal volume Liveness, is never of opposition. The very notion of liveness emerged due to the need to distinguish between recorded and live performances on the radio. [6] This conceptual and historical co-dependence finds in Callas in Concert a paradigmatic instance. From their seats in theatres and auditoriums around the globe, the spectators-listeners are given the opportunity of seeing the hologram of Maria Callas and hearing her recorded voice, while a live orchestra is performing on stage. Needless to say, neither the voice nor the body of the dead diva is entirely “real.” Contrarily to the orchestra and the conductor, the singer is not there, either in space or in time, despite the fact that Callas in Concert is a live show. Yet in their posthumous appearances, the diva’s voice and body are “unreal” in different ways. This distinction is not irrelevant and drawing attention to it allows me to better explain how the show was put together. [7]

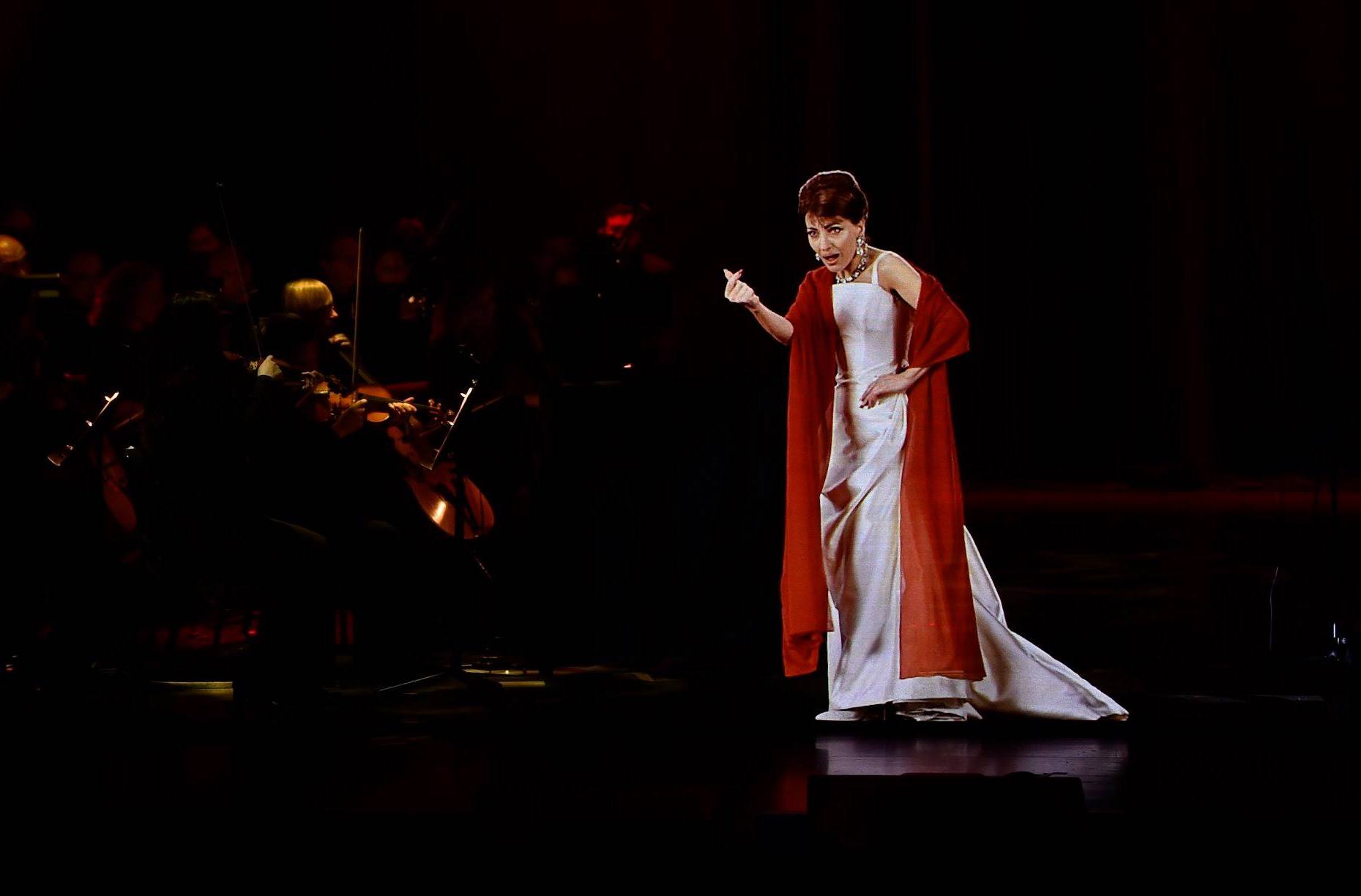

Compared to Callas’s reproduced voice, her projected figure is “unreal” to the second degree: the movements of the hologram, though inspired by the soprano’s bodily postures and gestures, are not hers. That is to say, the hologram is not a reproduction of any of Callas’s performances, but a reproduction of someone else reenacting her body language on stage. The company hired Stephen Wadsworth from the Juilliard School, who worked closely with an actress so that she would move and behave like Maria Callas. “We worked on Callas’ gestural language,” he recalls, “how she held herself, her physical life, down to how and when her fingers moved, and her symbiotic relationship with her gown.” The challenge, however, went beyond simply mimicking her gestures: “She [the actress] is three people up there,” the director adds, “the private Callas; Callas the public figure; and Callas as the character she is embodying in any given aria.” [8] The rehearsal process took twelve weeks, after which the double’s performance was recorded. It was this recording that a team of experts manipulated using new digital and laser imaging, and Computer-Generated Imagery, so that the hologram would resemble Callas in terms of physical appearance as well (figure 1).

Fig. 1. The hologram of Maria Callas next to a live performing orchestra. (© Evan Agostini/Base Hologram)

When it comes to the sonic part of the show, the creative process took a different path. We are actually listening to Callas’s voice: that is to say, to remastered recordings of her performances. In fact, a partnership was established between Warner Classics—the company that owns the rights to Maria Callas’s recorded legacy—and Base Hologram, thus allowing the show to be developed. Technology was crucial at this stage as well: the sound of the voice was carefully isolated from the sound of the orchestra, so that the original recordings of Callas’s voice, dating from the 1950s and 1960s, could be paired with the sound of live performing orchestras today. In each performance, it is the job of the conductor to ensure that no temporal mismatch occurs. [9]

This is not the first time that a deceased Callas “performs” with living artists. Angela Gheorghiu’s 2011 studio album Homage to Maria Callas gave online access to a video in which the two singers interpret the “Habanera” from Bizet’s Carmen in a duet. [10] In “The Limits of Operatic Deadness,” Carlo Cenciarelli rightly emphasizes that the dynamic of this “intermundane collaboration,” following Jason Stanyek and Benjamin Piekut, is less audacious than the announcement of a groundbreaking artistic project would suggest. [11] “The Habanera duet,” he claims, “shows a cautious approach to the boundaries that separate the dead from the living. And it shows that, when it comes to opera, such boundaries are heavily over-determined. … They protect the aesthetic identity of the popular aria, the memory of the immortal diva and the truth of the photographic image.” [12]

An apparently anodyne detail about the video confirms this diagnosis, while also serving as a touchstone to compare this intermundane collaboration with the holographic concert: the use of color versus black-and-white footage. Freedom to travel in time is not equally distributed in the Habanera duet; Callas stays in the past, or at least her image does, whereas Gheorghiu occasionally joins Callas on the evening of her 4 November 1962 concert at Covent Garden. [13] In other words, whereas their voices mingle in the performance of the original “solo” aria—which only the fact of being sung by two voices, be it in sequence or in unison, allows us to distinguish it from a conventional rendering—the images of their bodies remain technically and stylistically distinct. Most of the time, we see Gheorghiu inside a pentagonal studio surrounded by screens projecting videos of Callas. At a certain point, however, we also see the two singers side by side, as if Gheorghiu had travelled to the black and white past in which Callas remains stuck (figure 2). This marks a fundamental difference between the time-travelling video and the holographic show, since the purpose of the latter is first and foremost to bring Callas’s auratic presence to the present.

Fig. 2. Still frame from the “Gheorghiu-Callas ‘Habanera’ duet” video (EMI Classics Music Video. © 2011 EMI Records Ltd. All rights reserved).

But there is a second, perhaps even more important, difference between the two projects: Callas in Concert happens live, whereas the duet of Gheorghiu and Callas is a video recording. As a live performance, what is unique about Callas in Concert is the fact that the live-recorded matrix pervades both the audio and visual dimensions of the spectacle. The situation is not as simple as when the image is live and the sound is recorded (in shows, for instance, where the singer is lip-syncing) or, conversely, when the image is recorded and the sound is live (when an orchestra accompanies a silent film or, to give a more concrete example, in Philip Glass’s 1994 opera La Belle et la Bête, whose singularity consists in the fact that the instrumental and vocal parts were composed to match the pre-existing images of Jean Cocteau’s 1946 film). In Callas in Concert, both the auditory and the visual dimensions of the concert are partially recorded and partially live.

True, this is also the case whenever a video is projected on stage during a performance. However, the three-dimensionality of the hologram, surrounded by flesh and blood musicians on stage, suggests physical presence in a way that no video does. While this fact illuminates the singularity and the appeal of Callas in Concert, it also complicates its description. More than any other mediatized performance, holographic shows rely on fiction. To understand the stakes of such fiction is crucial to interpret Callas in Concert.

Callas in Concert has been—or was, before the pandemic hit—a box-office success. After a preview concert on January 14, 2018, at the Rose Theater in New York, Callas’s hologram went on tour in the United States, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Europe, and South America. People adhere to the concept of a live concert with the hologram of Callas because of their fascination with, interest in, or curiosity about the diva. I would argue, however, that the reasons behind the popularity of the show are more complex than they seem at first glance. Is the opportunity of seeing and hearing “La Divina” the only and main trigger?

I think the answer to this question is twofold. On the one hand: yes, of course; people go to the show because they want to experience the art of Callas with their own eyes and ears. On the other hand: yes, but not quite. For one simple reason: the possibility of seeing and hearing Maria Callas is not new. Recordings of her voice have been widely disseminated for decades. They have been remastered and re-remastered several times. [14] Photos and videos of Callas are not hard to find either. They are everywhere online. Google, for instance, has nearly fifteen million entries on her name. In short, and despite the fact that video recordings of Callas’s live performances are surprisingly scarce, opportunities to see and hear Callas on stage, backstage, performing, rehearsing, being interviewed, walking her dog in Paris, sunbathing on Onassis’s yacht, starring as Medea in Pasolini’s film, and so on, are not exactly rare.

What in any case is new, what this first-of-its-kind operatic show adds to all these instances of postmortem audio-visibility, is a “fiction of liveness” that none of the others possess. Although the artist is not physically present, the conductor interacts with the holographic double of Callas in front of the audience as if she was “really” there (figure 3). The spectators are also invited to suspend their disbelief. Indeed, most of them applaud at the end as if the singer—and not just the orchestra and the conductor—had performed live. In short, the whole point of the show is to bring Callas back: not to life, but rather to the stage—to resurrect Callas as a live performer.

Fig. 3. The hologram of Maria Callas gesturing at the conductor and vice-versa. (©Evan Agostini/Base Hologram)

Callas in Concert provides—and wants to be seen and heard as providing—a “drastic” experience. In fact, although only the orchestra and the conductor are physically present and performing live, the interaction between them and the pre-recorded, projected hologram happens hic et nunc. As always in a live performance, things can go wrong: the conductor might stumble; violin strings might snap; somebody in the audience might start singing; the diva’s disembodied voice and image, if a power cut occurred, would vanish immediately, while the orchestral music would continue for at least a few seconds. Although the concept of drastic, as Carolyn Abbate formulated it in “Music—Drastic or Gnostic,” refers first and foremost to physical presence and bodily engagement, the facts of technological mediation do not as such contradict it. As long as the thrill of unpredictability and the charm of ephemerality are in place, the drastic experience might well escape the claws of gnostic voracity. [15]

In sum, and to answer the question I raised above, the charm of authenticity that is still perceived as a sine qua non component of a live performance must to be taken into account in understanding why people adhere to the show. It is because Callas in Concert responds to a double fascination—with Maria Callas, certainly, but then also, not less important, with liveness and all the characteristics it entails—that the show has also been so popular. I will now consider these two fascinations in turn—with Callas, considering the actuality and the genealogy of her cult, and with liveness— before I draw a few broader conclusions.

Callas in Concert is not an isolated phenomenon. In fact, the admiration for the diva seems to be once again (or perhaps it has never ceased to be) in the air. The hologram show appeared in 2018 and was only possible, as I mentioned before, thanks to a partnership with Warner Classics. The label had recently launched two lavish box sets of Callas live and studio recordings. [16] Around the same time, French filmmaker Tom Volf, a self-proclaimed newcomer to the cult of Callas, had already dedicated four years of his life (which, he claims, was transformed by the encounter with Callas) to gathering unique archival sources, including testimonies and audiovisual materials, many of which were still unpublished. His efforts eventually culminated in “Maria by Callas,” a multi-object project including one documentary film, one exhibition, and three books. [17]

What is unique about this enterprise—or so a well-devised marketing strategy wants us to believe—is that for the first time it gives voice to Callas. [18] Needless to say, this is a well-worn—albeit still commercially-effective—cliché. At the same time, and despite the rhetoric of nostalgia and authenticity in which the project indulges, the fact that the documentary draws exclusively on words said or written by Callas does produce some interesting results. Acknowledging such merit is not meant to forget that no documentary is transparent. Although Callas’s words provide a filter through which Volf’s reading is conveyed, the film is the result of the filmmaker’s own sensibility, thoughts, and decisions (from the choice of materials to the narrative thread, up to the editing process). His film will always be a “Maria by Callas by Tom Volf.” [19]

To consider another recent example, Marina Abramović, after planning to consecrate a piece to Callas for a long time, has ultimately put her ideas into practice. After leaving behind different plans—including collaborating with several contemporary filmmakers—her 7 Deaths of Maria Callas, a performance-like opera, premiered on September 1, 2020, at the Bayerische Staatsoper. [20] The opera should have taken on the stage in April 2020. However, due to the pandemic, these performances were postponed and a few adaptations— mainly regarding the distribution of the musicians in the theater— had to be made.

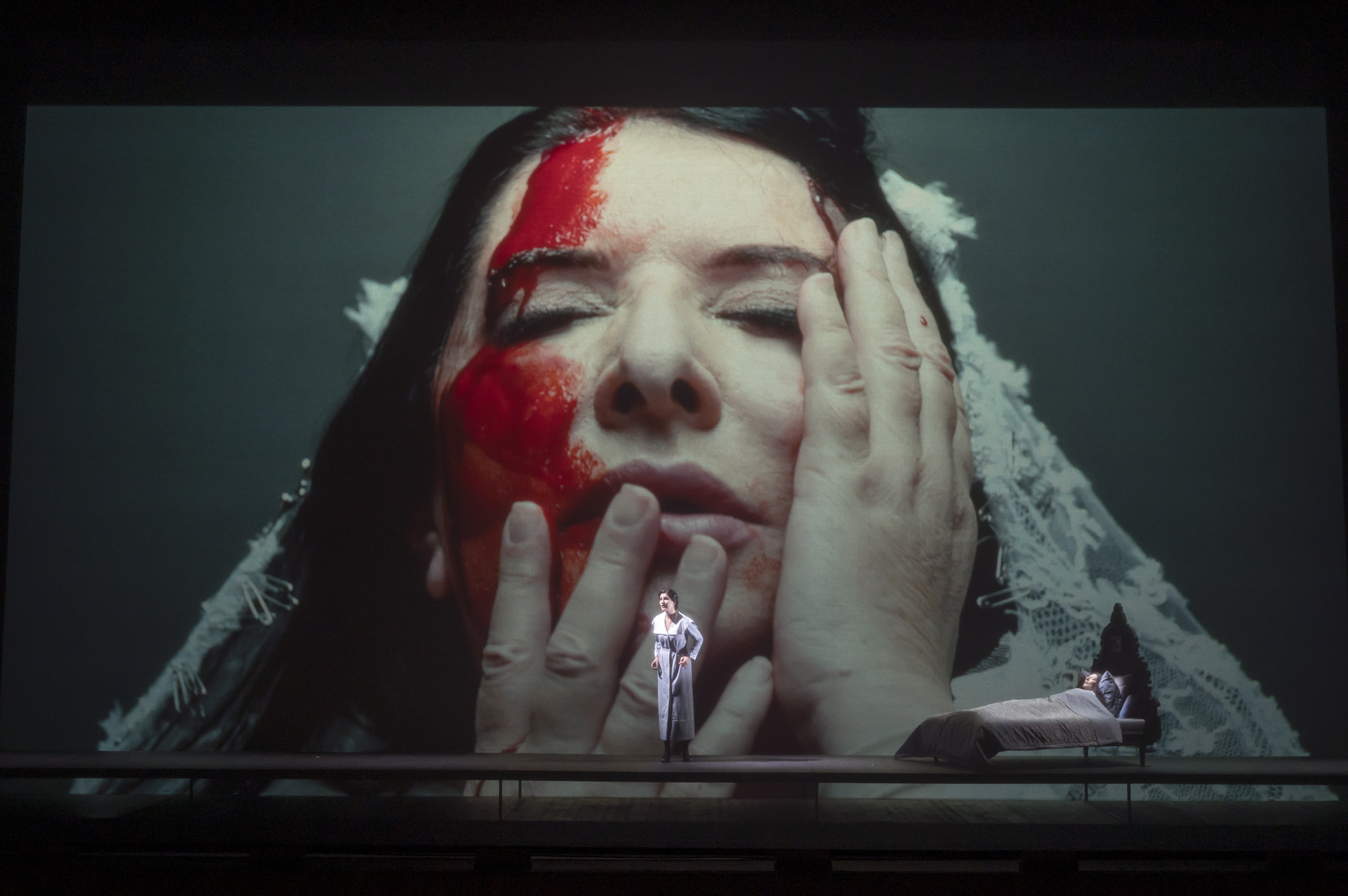

The production, which was live-streamed on the company’s website on September 5, 2020, includes seven major scenes in which seven sopranos sing seven famous arias from seven well-known operas: Verdi’s La traviata, Puccini’s Tosca, Verdi’s Otello, Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, Bizet’s Carmen, Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, and Bellini’s Norma. While each of these arias is performed live, a pre-recorded video by Nabil Elderkin is projected on the back of the stage. Marina Abramović stars in all of them, either alone or accompanied by William Dafoe, to incarnate the seven deaths of the above-mentioned characters under the sign of consumption, jumping, strangulation, hara-kiri, knifing, madness, and burning. But there’s an eighth death at the end: the death of Maria Callas herself. In this epilogue, which fictionalizes the circumstances of the singer’s death in 1977 in her Paris apartment, Marina—this time on stage, where she had been lying in a bed since the beginning of the performance—embodies Maria. It is also in this last scene that we have the chance to listen more to the music composed by Marko Nikodijević, who is also responsible for the composition of the prelude and the interludes between the scenes. [21]

Among other points of interest, Abramović’s project explores the sensual and imaginary transitions between what happens on stage and what happens on screen. This peculiarity also invites us to briefly compare Callas in Concert and 7 Deaths of Maria Callas. Both projects, unlike Maria by Callas, embrace fiction, yet while the former insists on the importance of liveness (for the price of giving up the corporeality of the performer), the latter seems to stake everything on presence (for the price of effacing both the voice and the image of Callas). Her voice is replaced by the voices of the singers. Her demeanor is reinvented by the postures and gestures of Abramović herself. This project, however, is not only a deeply personal homage to Callas in which the images of Marina and Maria are brought together as if not only their faces but also their personae were akin to each other—it is also an artistic experiment that questions the hegemony of presence and liveness. It does so, perhaps unintentionally, insofar as it makes it impossible to assign greater importance to the Marina on stage than to the Marina on screen. Since the same performer dominates the screen as much as the stage, the hierarchy between the two collapses (figure 4). In this sense, when it comes to the fiction of bringing the diva back to the stage, Callas in Concert is more literal. However ethereal and transparent, the hologram never ceases to appear as the real Callas performing on an actual stage.

Fig. 4. 7 Deaths of Maria Callas (© Charles Duprat—OnP)

In addition to an effervescent context, Callas in Concert also benefits from a long and complex genealogy. The Callas cult goes back to the years following the soprano’s death and persists, manifesting itself in both research-driven and fiction-based projects to this day. In cinema, for instance, films as diverse as Tony Palmer’s Callas (1978), Federico Fellini’s E la nave va (And the Ship Sails On, 1983), and Franco Zeffirelli’s Callas Forever (2002) embody quite different visions, although an element of veneration seems nonetheless pervasive in all of them. I will not consider this genealogy in depth, let alone delve into the consideration of what seems to be its seminal episode: the cremation of Callas’s body and the scattering of her ashes to the sea. [22] Instead, I propose two hypotheses that may shed some light on how the Callas cult intersects with a broader debate on the contemporary fate of opera. The first concerns the connection between the historical and mythical dimensions of the Callas cult, while the second suggests that this cult has known two peaks since the death of the singer.

As Marco Beghelli claims, the importance of the singer and actress in the history of opera needs to be acknowledged beyond the myth. Callas opened the path to and provided the model for a new operatic subjectivity. “By affinity or sheer instinct,” Callas became “the vocal and dramatic instrument for the rebirth of the bel canto tradition.” [23] However, according to Beghelli, this is just the tip of the iceberg. Not only did Callas reconnect coloratura singing and dramatic truth—she also explored, with her “grainy,” “uneven,” and “ugly” voice, the ambivalence between female and male timbres as well as the transition between contralto and soprano registers. All this, and especially her capacity to reconcile “the personal need for reinterpretation and the faithful adherence to the composer’s intention” made of Callas a model for the coming generations of singers. [24]

Following Beghelli, while also putting some pressure on his argument, it bears adding that it is impossible to completely excise myth from history when it comes to Callas. The terms used by Beghelli to capture the singularity of Callas are telling in this regard, namely when he claims that “Callas proposed her own interpretation of coloratura as a completely individual outcome, having no living model from which to take her inspiration,” something she did “instinctively.” [25] This formulation is curiously reminiscent of Kant’s definition of genius. As “the talent … which gives the rule to art,” the genius has no model. [26] It corresponds to an innate creative aptitude, which they exercise instinctively, being unaware of what they do. Of course, when it comes to the performing arts, the notions of talent, genius, or creativity are as much a matter of creation/production as of recreation/reproduction. But, as long as the myth of the genius survives, the values of originality and singularity persist, despite the need to negotiate an alliance between the “genius of the composer” and the “genius of the performer.” The question, however, arises whether identifying the “historical modernity” and “everlasting relevance” of a performer with their capacity to put their subjectivity at the service of the “objectification of the score” is not itself another myth. [27]

This interrogation paves the way for my second hypothesis. In fact, looking at the previous decades without forgetting the inextricability between the mythical Callas and historical Callas, there seems to have been two golden ages in the Callas cult: the 1980s and 2010s, that is to say, the two decades in which the subgenre of opera film, in the first case, and the cinecast phenomenon, in the second case, reached their peaks of popularity. [28] I don’t think this is a coincidence. Could the obsession with the diva’s death not be seen as a symptom of the broader preoccupation with the demise of the genre? This would explain why the cult of the diva reemerges each time the debate about the genre’s survival, and the media fuss around it, is on everybody’s lips.

Beyond these two hypotheses, one thing is certain: today, whenever the promoters, critics, spectators, fans, or detractors of Callas in Concert talk or write about it, the metaphor of “resurrection” consistently emerges. Furthermore, this metaphor seems to be all the more effective when it presupposes a symbiosis between the artist (Callas) and the genre (opera). One says “diva,” yet one also means “opera,” and vice versa. “Many are already resigned to watching old videos or listening to old recordings,” David Salazar comments in the Opera Wire, “but there are some that have different ideas. In fact, their ideas involve bringing her back.” [29] Of all critics, Anthony Tommasini has been the most explicit in emphasizing how closely the admiration for the artist and the concern with the genre intertwine, while also acknowledging the uncanny mixture of attraction and repulsion triggered by the spectacle:

It was amazing, yet also absurd; strangely captivating, yet also campy and ridiculous. And in a way, it made the most sense of any of the musical holograms produced so far. More than rock or hip-hop fans—and even more, you could say, than fans of instrumental classical music—opera lovers dwell in the past. We are known for our obsessive devotion to dead divas and old recordings; it can sometimes seem like an element of necrophilia, even, drives the most fanatical buffs. [30]

This association of opera to death, murder, and suicide is far from being an anodyne feature of the genre. In Temple of the Scapegoat, Alexander Kluge follows the threads of various stories of sacrifice punctuating the history of the genre. These include anecdotes, such as the death of baritone Leonard Warren, while passionately interpreting Don Carlo in Verdi’s La forza del destino on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera House in 1960, which for Kluge emblematizes “Warren’s total commitment—his readiness to sacrifice his own life;” [31] or an episode during the Nazi occupation of Paris, when the entire cast of a production of Beethoven’s Fidelio got trapped in underground rehearsal rooms of the Palais Garnier, where they kept working nonetheless. “Busy with their rehearsals,” Kluge comments, “these lost souls in the opera’s bowels were blind to the desperate nature of their situation. Their bread and water were as tightly rationed as in a Spanish prison at the actual time the opera was set.” [32]

Seen from the perspective of gender, the problematic nature of such “sacrifice mania” boils down to the following perplexity: why does the soprano have to die in the end? Why always (or almost always) the soprano? Why is the price of tragic enjoyment to be paid by the female protagonist? In Opera, or The Undoing of Women, Catherine Clément explores this issue with insightful vehemence:

Opera concerns women. No, there is no feminist version; no, there is no liberation. Quite the contrary: they suffer, they cry, they die. Singing and wasting your breath can be the same thing. Glowing with tears, their decolletés cut to the heart, they expose themselves to the gaze of those who come to take pleasure in their pretend agonies. Not one of them escapes with her life, or very few of them do. [33]

Clément’s book has been widely debated and contested. Abbate, for instance, was unconvinced by Clément’s focus on the libretto, and agreed with Paul Robinson in claiming that when it comes to pondering the fate of these operatic heroines, their vocal triumph cannot be downplayed, let alone ignored. [34] There may be other ways of putting pressure on Clément’s reading that do not rely on the dichotomy of music and text—the text itself, in which the undoing of women becomes explicit, is prone to multiple interpretations. In any case, from Catherine Clément to Marina Abramović—but also to Christophe Honoré, who directed a production of Tosca for the 2019 Aix-en-Provence festival, focused on the figure of the diva—the entanglement of adulation and violence that impregnates opera’s attitude toward women, both in fiction and in reality, remains a most debated topic among scholars, critics, and artists, one on which Callas in Concert also takes a stand.

As I mentioned before, Stephen Wadsworth’s curatorial work went beyond choreographing the actress. It also involved devising a script reflecting the story of Maria Callas. In this regard, it is significant—and a sign that Callas in Concert is not only a business-oriented, but also an artistic endeavor—that in some versions of the concert the program kicked off with “Je veux vivre” (from Charles Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette) and wraps up with the monologue “Suicidio!” (from Amilcare Ponchielli’s La Gioconda), as if suggesting that, at least in her afterlife as a hologram, Callas regains power over her destiny. [35] She wants to live, and it is by expressing such a desire that her posthumous show begins. It will not end before she decides, in hopes perhaps of holding those who rejected and betrayed her to account, to commit suicide. Would there be an alternative way to put an end to the show? This question remains in the air.

6. To applaud or not to applaud

The “Suicidio!” may well be the last piece announced in the program. But will it be the last aria performed? Will the hologram of Callas not sing an encore? How willing will she be to take the audience’s wishes into account in making such a decision? These questions lead us back to the topic of liveness. It may, however, come as disappointing news for many spectators that the holographic diva, albeit keen to sing encores, will not be able, regardless of the audience’s reactions and wishes, to improvise her decisions. After all, technology has its limits—limits that one may either lament (while looking forward to new developments) or commemorate (as a proof that the gimmick has its flaws).

The question of whether the hologram of Callas will play an encore or not leads me to the consideration of a Live in HD broadcast of Donizetti’s La fille du régiment in 2019. In her introductory remarks, soprano Nadine Sierra announced that for the first time in the history of The Met: Live in HD series an encore during the performance might indeed happen. She had in mind Javier Camarena’s delivery of “Ah! Mes amis,” which in previous evenings had triggered the applause of the audience to the point of encouraging the tenor to resume the aria from the beginning. Her prediction turned out to be exact and Camarena did sing the number twice. [36]

I recall this episode because I think it bears interesting similarities with the pre-planned encores of Callas in Concert. Of course, there are many differences between a hologram show and a live cinecast. However, in light of their analogous treatment of the encore, they both seem to lay bare the oscillation between predictability and unpredictability that characterizes a great number of live-mediatized performances today. I find this convergence symptomatic of how intricate and tense the marriage of operatic tradition and technological innovation has become in recent years. In fact, whether the drastic element is reconcilable with audiovisual remediation is a question to which both enthusiasts and detractors of technological innovation are far from being indifferent.

Now, I would like to turn the discussion to the audience’s perspective by considering a brief reportage after the Paris concert at the Salle Pleyel in which several spectators share their impressions on the show. Here are some statements worth considering:

-

- It’s pretty powerful. You really feel like she’s there. I don’t know how it’s possible.

- She’s there, she’s present. It’s an exceptional vibrato.

- Callas has always touched me, and here she didn’t. And that’s a shame.

- She comes on like a diva, waiting for everyone to stand up and scream … and there’s some timid applause. People are wondering “is this art? is it serious? do I get on board or not?” And we’re captivated. It’s scary. [37]

To applaud, or not to applaud, that is (also) the question. The responses, as the previous pronouncements show, vary significantly between excitement and disappointment. However, there seems to be something in common between those who applaud and those who do not applaud, between those who are excited and those who are disappointed: the idea that a spectacle with the hologram of Callas, much like a live concert featuring her, is meant to move the audience, to making it feel “touched.” In fact, what the gentleman who says that “you really feel like she’s there” and the young lady who corroborates “she’s there […], it’s an exceptional vibrato” share with the Callas admirer who laments “Callas has always touched me [ m’a toujours fait vibrer], and here she didn’t” is the assumption that “making you vibrate” is the gauge on which a judgment aboutCallas in Concert should be made. They differ as towhether the show achieves the goal. Yet they all agree about what the goal is: namely, nothing less than reproducing the sense of uniqueness, exceptionality, and authenticity associated with attending a live performance of Maria Callas.

Could we then conclude that reproducing the aura of Maria Callas as a live performer is what Callas in Concert is all about? As I suggested above, the fascination with the diva’s charismatic presence and the fascination with the charm of liveness are the two ingredients behind the success of Callas in Concert. However, since Maria Callas is not physically present on stage (nor is an actress embodying her, as is the case with Abramović in 7 Deaths of Maria Callas), it is not the aura of the performer (the “originality” of their bodily presence) that is being reproduced. What is being reproduced, evoked, emulated is the aura of the performance (the “originality” of a live event happening hic et nunc). [38] And yet, Callas remains the raison d’être of the show. In order to avoid this somewhat paradoxical formulation, we could perhaps say that what is being reproduced in Callas in Concert is the persona—not the aura—of Maria Callas as a live performer.

In his recent book In Concert: Performing Musical Persona, Philip Auslander returns to the notion of “persona” to discuss the identity of musical performers. [39] Instead of thinking of the musical performer as a real person who may or may not—depending on whether they are portraying fictional entities (as singers sometimes do)—embody different personae, Auslander argues that the identity of all and every performer consists of a persona. Whenever they play or sing for an audience, performers, however modest or self-effacing their playing or singing might be, are immediately performing their own identity (which is not the same as expressing themselves). In making this claim, Auslander emphasizes that, no matter the genre, style, aesthetic, idiosyncrasy, character, race or gender, the identity of the performer, to the extent that it is socially and culturally constructed, is always already, to a certain extent, a fiction.

While Auslander does not intend to undervalue the importance of corporeality in musical performance, he nonetheless notes that he has in mind “all instances in which musicians play for an audience, including on recordings.” [40] Therefore, to the extent that it applies to live and recorded performances alike and stresses the fictional dimension of musical identity, the concept of “persona” also sheds light on how a show that turns around the admiration for an absent, long-dead artist can be so effective. Moreover, since the hologram of Maria Callas portrays different characters in this concert, while at the same time never ceasing to behave as Maria Callas on stage, it seems adequate to claim that the “persona” of Maria Callas —notwithstanding her disembodied, technically reproducible substance (which is incompatible with the intimation of bodily presence that the notion of “aura” entails)—is indeed the core of Callas in Concert.

The fiction of a live concert with a dead diva sets boundaries to the imagination that some critics, consciously or not, were eager to police. As I conclude, instead of looking at complaints about how the spectacle fails in its attempt to emulate a live concert with Maria Callas, I want to briefly consider reactions that go in the opposite direction.

Wondering about what the future could bring, critic Richard Fairman speculates: “At the speed technology is advancing, just imagine where this could lead. We could have operas starring imaginary casts from the past. How about Verdi’s La traviata with Callas and Enrico Caruso? Or Nellie Melba and Luciano Pavarotti? Neither pair was alive at the same time, but that will not matter any more.” [41] In the same vein, but going even further, media theorist Tien-Tien Jong wrote (after attending the show at the Lyric Opera in Chicago in September 2019):

Maybe it’s because our seats were way up in the balcony, and I spent most of the evening squinting down at the stage, but I kept thinking: why not use a skyscraper-sized Maria Callas, looming like a Godzilla monster over the Lyric orchestra? […] And why does the fantasy to recreate one of her concerts mean investing so much effort in constructing a strange deepfake of Callas to realistically lip-sync along to old recordings […] instead of revolutionizing concert technology in a different way, like giving the audience really great headphones and a video headset to imitate attending an intimate chamber recital with Callas instead? [42]

Although a Godzilla-sized hologram of Callas might seem a bit over the top, I find these questions thought provoking. Richard Fairman’s “imaginary casts” underline that the hologram technology virtually effaces spatiotemporal boundaries, yet he does not question the assumption that everything should look like a regular live concert. That’s exactly what Tien-Tien Jong’s more radical fantasy does in suggesting that, along with spatiotemporal coordinates, realistic conventions and audiovisual habits can also be challenged. Following such a line of inquiry opens up a much more interesting discussion. When we look back at the tradition of opera films, we bump into works such as Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’sThe Tales of Hofmann (1951) and Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Parsifal (1982), which not only defied lip-syncing protocols but also played with ontological boundaries, such as the human/machine and the male/female divides. [43] A priori , there is no reason for a hologram spectacle to shy away from exploring experimental paths along similar lines.

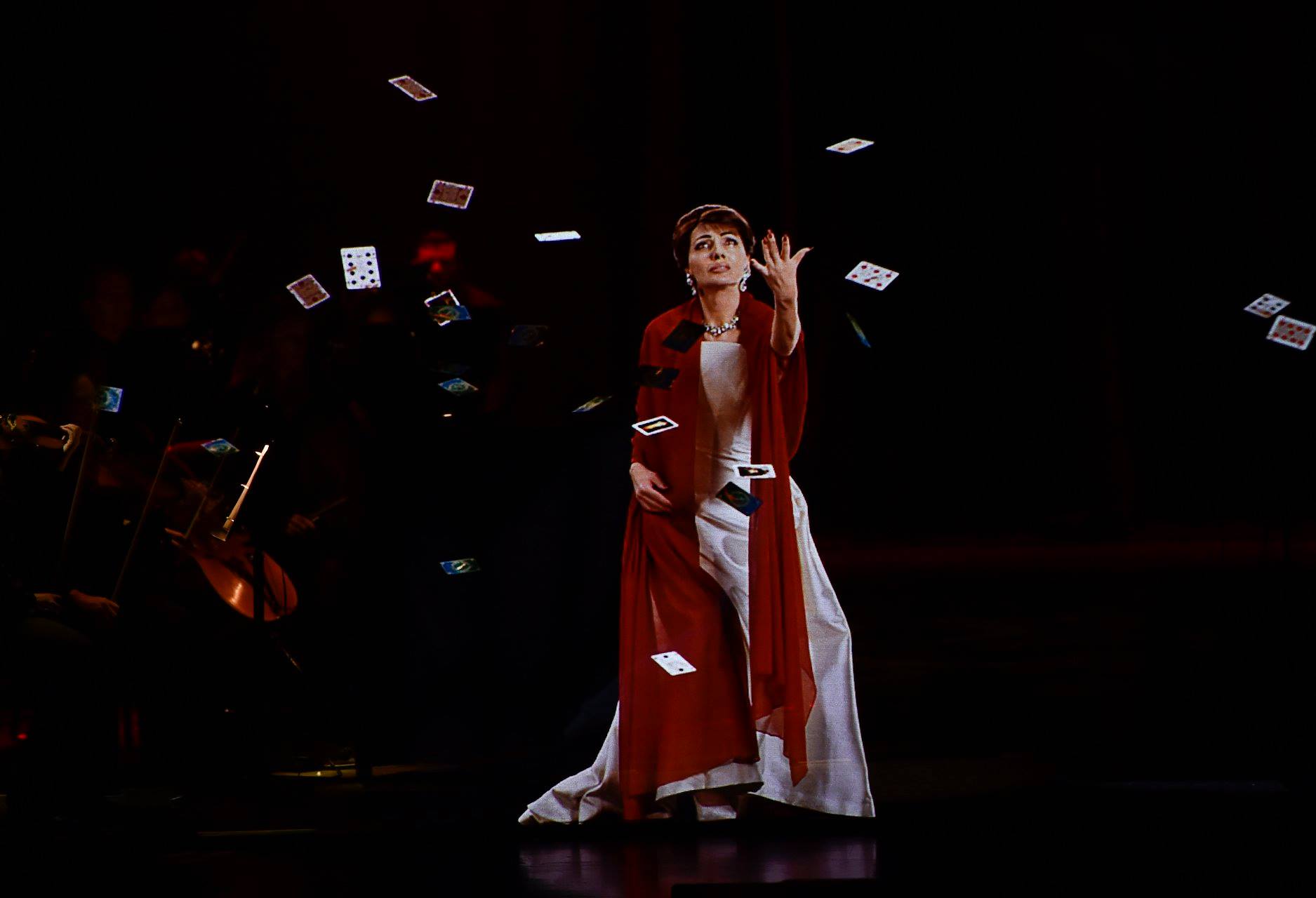

In practice, it would perhaps be naive to expect such a project to risk disappointing traditional operagoers even further. Some of Callas’s fans were quite taken aback already. Be that as it may, it would be inaccurate to say that Callas in Concert fully complies with the principles of realism. The scene with the playing cards falling in slow motion is a noticeable exception and stands out as one of the most suggestive moments of the concert (figure 5). [44] It contains a seed of fantasy that contrasts with the otherwise conventional tricks of the show. It also occurs at a significant moment—i.e., when the “card scene” from Bizet’s Carmen transitions into the “sleepwalking scene” of Verdi’s Macbeth. As soon as the cards, on which the future can be read, are thrown into the air, time is out of joint. The image slows down while the sound keeps its pace. It is as if we have entered a dream.

Fig. 5. The playing cards scene in Callas in Concert. (©Evan Agostini/Base Hologram)

This dream is not only a reminder that the show boils down to an illusion (this is, in a sense, the Brechtian moment of the show, in which the “fiction” of the hologram denounces itself in front of the audience). It is also an allegory of our time’s fears and desires. In fact, I think that this scene, considering the mix of perplexity and fascination it may cause, shows how strongly the fear of losing presence and liveness acts in the opera world. Would the essence of opera, as a live performing art, not be damaged by these losses? The question may sound obsolete today, as we acknowledge that not only technology and opera are inseparable, but also that the notion of liveness can only make sense in a highly mediatized culture. As Karen Henson argues, following Auslander and Jonathan Sterne, “the very idea of opera’s essence being live and technologically unmediated singing is a product of technology, for one cannot have an ideal of unmediated singing unless one is in a profoundly technological environment.” [45]

However obsolete it may be, the question also expresses an anxiety that intensified during the pandemic as a defensive mechanism against the boom of online events. Luckily, the resulting rhetoric that reserves the label of “operatic” to performances in which the physical copresence of singers, musicians, and audiences is preserved does not have the last word. In fact, the scene of the flying cards also suggests how radically new technologies can stimulate and enliven operatic imagination to the point of challenging the genre’s most ingrained musical and theatrical conventions. When we wake up from the dream, reality won’t be the same.

* I am grateful to the two anonymous readers who provided critical observations and detailed suggestions. This work is funded by national funds through the FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the Norma Transitória – DL 57/2016/CP1453/CT0059.

[1] For a philosophical reflection on how the pandemic—having accelerated the digital revolution and brought awareness to its ethical, social, and political consequences—transformed not only the way we imagine the arts, especially the performing arts, but also our experiences of love, travel, and study, see my recent book The Digital Pandemic: Imagination in Times of Isolation (London: Bloomsbury, 2022).

[2] See “Maria Callas: Callas in Concert,” Productions, BASE Hologram, accessed February 10, 2022.

[3] “BASE Entertainment Announces New Cutting Edge Live Entertainment Company: BASE Hologram,” News, BASE Hologram, posted January 11, 2018.

[4] It could be questioned whether it is accurate to say that BASE Hologram features a hologram of Maria Callas. The doubt is plausible not the least because, as I will explain below, the holographic apparition of the diva is based on the recording of an actress representing the soprano, rather than on the recording of any of Callas’s performances. That having been said, for the purposes of this article, I’m less interested in discussing the definition of holography than in examining the phenomenology of the show—a show in which a 3D image of Maria Callas, synchronized with live and recorded music, appears and behaves on stage as a live performing artist.

[5] Andreas Huyssen, After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986).

[6] Philip Auslander, Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture (New York: Routledge, 1999), 59.

[7] Here I use the terms “real” and “unreal” with the sole purpose of explaining how the show is constructed. On a more fundamental level, these elements—live performers, video projections, or holographic images—are all, as components of a live performance, absolutely real and equally significant.

[8] Stephen Wadsworth quoted in David Salazar, “Bringing Maria Callas Back to Life,” Opera Wire, June 16, 2018.

[9] For a preview of the show, see “Callas in Concert: The Hologram Tour,” video trailer, uploaded on May 27, 2019.

[10] “Angela Gheorghiu & Maria Callas – Habanera,” music video, uploaded on November 20, 2011.

[11] Carlo Cenciarelli, “The Limits of Operatic Deadness: Bizet, ‘Habanera’ (Carmen), Carmen, Act I,” Cambridge Opera Journal 28, vol. 2 (2016): 221–26; the reference is to Jason Stanyek and Benjamin Piekut, “Deadness: Technologies of the Intermundane,” TDR: The Drama Review 54, no. 1 (2010): 14–38.

[12] Cenciarelli, “The Limits of Operatic Deadness,” 225. Cenciarelli’s reflection culminates in the following observation: “the Habanera duet can be seen as a representation of what is at stake in the debate about opera and digital culture: not so much the survival of the operatic canon, its canonical performances and canonised performers, but rather the role that media will play in their afterlife” (225).

[13] Although most of the footage used in the video is taken from this concert, the sound recording (of Callas’s voice, not of the orchestra) originates in a studio performance with the Orchestre national de la radiodiffusion française, made for EMI between March 28, and April 5, 1961.

[14] On Callas’s recordings, see Giorgio Biancorosso, “Traccia, memoria e riscrittura. Le registrazioni,” in Luca Aversano and Jacopo Pellegrini (eds), Mille e una Callas. Voci e studi, Macerata: Quodlibet, 2016, 293-306.

[15] For a challenging reflection on Abbate’s theory of the “drastic,” see Martin Scherzinger, “Event or Ephemeron? Music’s Sound, Performance, and Media (A Critical Reflection on the Thought of Carolyn Abbate),” Sound Stage Screen 1, no. 1 (2021): 145–92.

[16] Maria Callas Remastered – The Complete Studio Recordings (1949–1969) , Warner Classics, 0825646339914, 2014, box set (69 CDs, 1 CD-ROM); Maria Callas Live – Remastered Recordings 1949–1964, Warner Classics, 190295844707, 2017, box set (42 CDs, 3 BDs).

[17] Maria by Callas , documentary directed by Tom Volf (Elephant Doc, Petit Dragon, and Unbeldi co-production, 2017); Maria by Callas, exhibition created and curated by Tom Volf (La Seine Musicale, Île Seguin, Boulogne-Billancourt, France, September 16–December 14, 2017); Tom Volf, Maria by Callas: In Her Own Words (New York: Assouline, 2017); Tom Volf, Callas Confidential (Paris: Éditions de La Martinière, 2017); Maria Callas, Lettres & Mémoires, ed. Tom Volf (Paris: Albin Michel, 2019).

[18] On the director’s personal website, a brief presentation of the documentary reads as follows: “Tom Volf's Maria by Callas is the first film to tell the life story of the legendary Greek/American opera singer completely in her own words.” See “Tom Volf – Director, Producer, Photographer,” accessed February 22, 2022.

[19] For a brief analysis of Maria by Callas, see João Pedro Cachopo, “The Aura of Opera Reproduced: Phantasies and Traps in the Age of the Cinecast,” The Opera Quarterly 34, no. 4: 271–72.

[20] See “7 Deaths of Maria Callas,” video trailer, Bayerische Staatsoper, uploaded on September 1, 2020.

[21] For a “multivocal” examination of 7 Deaths of Maria Callas , see “Review Colloquy: 7 Deaths of Maria Callas, Live stream from the Bayerische Staatsoper, Munich, September 2020,” ed. Nicholas Stevens, The Opera Quarterly 36, no. 1-2 (2020): 74–98. See also Jelena Novak, “The Curatorial Turn and Opera: On the Singing Deaths of Maria Callas. A Conversation with Marina Abramović and Marko Nikodijević,” Sound Stage Screen 1, no. 2. (2021): 195–209.

[22] For an exploration of this episode, in the context of an insightful reading of Fellini’s E la nave va, see Michal Grover-Friedlander, Vocal Apparitions: The Attraction of Cinema to Opera (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), chap. 6 “Fellini’s Ashes,” 131–52.

[23] Marco Beghelli, “Maria Callas and the Achievement of an Operatic Vocal Subjectivity,” in The Female Voice in the Twentieth Century: Material, Symbolic and Aesthetic Dimensions , ed. Serena Facci and Michela Garda (London: Routledge, 2021), 46.

[24] Beghelli, “Maria Callas,” 44.

[25] Beghelli, 48.

[26] Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, § 46, trans. James Creed Meredith (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 136.

[27] Beghelli, 57.

[28] On the opera film debate, see Marcia J. Citron, Opera on Screen (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000); on the cinecast phenomenon, see James Steichen, “The Metropolitan Opera Goes Public: Peter Gelb and the Institutional Dramaturgy of The Met: Live in HD,” Music and the Moving Image 2, no. 2 (2009): 24–30 and “Opera at the Multiplex,” ed. Christopher Morris and Joseph Attard, special issue, The Opera Quarterly 34, no. 4 (2018).

[29] Salazar, “Bringing Maria Callas Back to Life.”

[30] Anthony Tommasini, “What a Hologram of Maria Callas Can Teach Us About Opera,” New York Times, January 15, 2018.

[31] Alexander Kluge, Temple of the Scapegoat, trans. Isabel Fargo Cole, Donna Stonecipher, and others (New York: New Directions Books, 2018), 4.

[32] Kluge, Temple of the Scapegoat, 14.

[33] Catherine Clément, Opera, or The Undoing of Women, trans. Betsy Wing (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988), 11.

[34] Carolyn Abbate, Unsung Voices: Opera and Musical Narrative in the Nineteenth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991), ix; Paul Robinson, “It’s Not over until the Soprano Dies,” New York Times, January 1, 1989.

[35] This was the case for the performance of September 7, 2019, at the Lyric Opera of Chicago. See Maria Callas in Concert, program notes, September 7, 2019, Lyric Opera House, Chicago.

[36] See The Metropolitan Opera, “On opening night of the 2019 revival of Donizetti’s La Fille du Régiment, tenor Javier Camarena made history by becoming one of only a handful of soloists to give an encore on the Met stage,” Facebook, June 29, 2020.

[37] N. Handel, A. Mesange, R. Moussaoui, “Astonishment as hologram, live orchestra put Callas back onstage,” AFP News Agency, post-show video reportage, Salle Pleyel, Paris, uploaded on November 29, 2018.

[38] It is a complex question how the notion of aura, and the very dichotomy of original and copy, can be applied to the performing arts. In any case, if we address this question in light of Benjamin’s theory of technological reproducibility, it becomes clear that, when it comes to the performing arts, the experience of the aura is associated not so much with the contact with an artwork as with the attendance of a performance: the performance—in its uniqueness and ephemerality—is the original that can be reproduced. Meanwhile, as there is no performance without performers, the fact that performers and audiences are co-present in time and space is also part and parcel of that sense of originality.

[39] Philip Auslander, In Concert: Performing Musical Persona (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021). See also “Musical Personae,” TDR/The Drama Review 50, no. 1 (2006): 100–119, “On the Concept of Persona in Performance,” Kunstlicht, vol. 36, no. 3 (2015): 63–64, and “‘Musical Personae’ Revisited,” in Investigating Musical Performance: Theoretical Models and Intersections , ed. Gianmario Borio, Giovanni Giuriati, Alessandro Cecchi, and Marco Lutzu (London: Routledge, 2020), 41–55.

[40] Auslander, In Concert, 91.

[41] Richard Fairman, “The Immortal (Hologram) Maria Callas,” Financial Times, November 2, 2018.

[42] Tien-Tien Jong, “Maybe it’s because our seats were way up in the balcony,” Facebook, September 23, 2019.

[43] See Citron, Opera on Screen, chap. 4 “Cinema and the Power of Fantasy: Powell and Pressburger’s Tales of Hoffmann and Syberberg’s Parsifal,” 112–60.

[45] Karen Henson, “Introduction: Of Modern Operatic Mythologies and Technologies,” in Technology and the Diva: Sopranos, Opera, and Media from Romanticism to the Digital Age , ed. Karen Henson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 22.