REFLECTIONS

Music Criticism in the Age of Digital Media

with two contributions by Benjamin MiNiMuM/Angèle Cossée, and Peter Uehling

edited by Klaus Georg Koch

Sound Stage Screen, Vol. 2, Issue 1 (Spring 2022), pp. 107–160, ISSN 2784-8949. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. © 2022 Klaus Georg Koch. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54103/sss18439.

Among the many notions between God and humanity lately declared “dead,” neither music critics nor music criticism have been spared. There are numerous articles, YouTube-videos, round-table discussions, and books featuring “the death of the music critic,” claiming that “music criticism is dead,” or pursuing a manhunt for the persons having “Killed Classical Music.” The threat of extermination looms even where hope is nurtured, as others ask: “How can music journalism survive digitalization?” [1]

It may be wise from the beginning to put the death of-topos in perspective as a stratagem to affirm the life of the persons using it. After all, living means to bear witness to things, people, institutions, ideas, and convictions pass away. As we perceive something is ending, something different may come into existence, as Hegel argues where he explains his reasons for the “end of art.” [2] The topos seems to express the dark side of modernisation, and to mark the losses in a Schumpeterian process of “creative destruction,” a concept that originates in economics but is implicitly based on a philosophy of life that features the mother of all proclaimed deaths, that of God. [3]

Yet, where a sense of loss prevails, something is likely to be disappearing. Music criticism as both a practice and institution, and the critic as a role model and profession, have come under strain. Figuring for more than a century as part of generalist newspapers’ offerings predominantly in the European west, as well as a key feature in specialist magazines, music criticism has become a casualty of the seemingly secular decline in audience and revenues. [4] Permanent full-time jobs have been cut, many of the remaining critics carry on in precarious labour relations. With the advent of social media, arts organisations have begun to elude intermediation by established media and to communicate with their public directly. In this understanding of disintermediation, contributions by music critics are on the downgrade as “secondhand opinions.” [5]

Is music criticism getting allotted a place in the museum of obliterated practices and deserted discourses? Can it prevail by inserting its proven contents and manners of operating into new media techniques and formats, as Christopher Dingle and Dominic McHugh seem to assume? [6] Is there a path of adaptation or innovation discernible in the proceedings of the digitally formatted discourse on music?

These are the questions this text will try to help elucidate. Rather than applying a fixed framework, I will seek to find out what the main forces behind present transformational processes affecting music criticism are. The general perspective is that of media change, whereby “media” are understood as dispositives entailing technological apparatuses, communication structures, discourse practices, role models, and their institutionalisation. The products generated in media systems shall be understood, following Siegfried J. Schmidt, as “social instruments for the structural linking of cognition and communication, thus for the linking of actants, organisations, institutions, and enterprises in the symbolic space.” [7] Media change, for its part, will be considered within a larger prospect of a history of ideas. While these definitions may appear rather broad, they steer clear of the kind of technological determinism often found in debates about “the future of music criticism.” Through them I will attempt to counter any short-termism in the appraisal of technological innovation and the resulting changes in the mediascape fed by a widespread perception of “the rapid development of new digital media.” [8]

Metaphors of Depth

In pursuing such a program, this text focuses on a “German” conception of music criticism. The reference to Kantian, Hegelian and, as we will see, post-Hegelian perspectives is being chosen because it can help explain present strains on music criticism not primarily dependent on media change. Irony will help keeping national stereotypes at bay, similarly to the irony adopted by composer, conductor, and writer Ferdinand Hiller in 1884 when comparing contemporary music culture in Italy with practices then understood as typically German. Not only did he mention the obsession with “founding one musical newspaper after another” and writing “critical-aesthetical” articles, but he also referred to “German depth” in musical discourse. [9]

As Holly Watkins has shown, metaphors of depth pervade German reasoning from Wackenroder’s early romanticism to Arnold Schönberg’s musical thinking. [10] Arguing with Albrecht Koschorke’s theory of the emergence of a new topology of subjectivity towards the end of the eighteenth century, “depth” may be considered as one of the terms expressing a shift of their frame of reference “from transcendental subjectivity towards the empirical-psychological individuum.” [11] “Depth” was assigned a function in the dichotomy between “profound” and “superficial.” It also marked a position on a vertical axis ranging from the chthonic to the transcendental, as opposed to “breadth.”

Since the end of the eighteenth century, music criticism has not only tried to assess “depth” in musical works, [12] it has also aimed to be profound itself. If music is understood as the semiosis of a “hidden dimension where nature, man, and spirit intersect,” as per Watkins’ summary of Wackenroder’s theory of musical art, [13] music critics have been trying to capture through language what would otherwise fade away without entering the sphere of discourse. Until the invention of Charles Cros’s paléophone and Thomas Alva Edison’s phonograph in 1877, “deep” music criticism was therefore an invocation of the ephemerality of everything said, sung, and played. It was an objectivisation via written language, a transmediation instituting music-centered public discourse.

If “breadth” in discourse about music does not seem to be a problem today—news about “who is doing what” in musical life are being announced, told, reported, posted, and retweeted through all channels and in all manner of media—the pursuit of “depth” is perceived as a losing proposition. This, in the last analysis, is the reason behind many critics’ grief and dismay, and Peter Uehling’s contribution to this subject (see Appendix 1) may be read as a critic’s document of the sensation of being marooned or outcast by changing discursive and media practices. Uehling’s Wutrede (rage address) reminds us of the fact that “change” in cultural matters is always embodied, and that changing media practices entail a revaluation of human capital as well as changes in the quality of communicative relationships.

Invocation and discursivation find themselves intertwined in Theodor W. Adorno’s influential conception of music criticism. On the one side, the musical artwork itself is seen by Adorno as being in need of critical discursivation. On the other side, both musical experience and reflection on music are needed for the project of emancipation—and more emphatically: constitution—of the modern subject. Adorno understands musical artworks as processes that unfold their essence “in the time,” as he puts it. This unfolding of art (to use the botanical metaphor) is realised through “the medium of commentary and critique.” [14] Therefore, music criticism is not just “a means of communication.” Adorno understands it as an activity and a form of discourse in its own right that complements the artwork. [15] In this process of transmediation—or more emphatically: transubstantiation—the critic exercises what according to Adorno is the essence of musicality: “to think with one’s ears the unfolding of what becomes sound in its necessity.” [16] Music itself may both express and influence the “deep” instances of human existence. Music criticism then subjects sound to linguistic reason. Within its sphere of duties, defined by the post-Hegelian teleology of the subject, it has to enhance the level of awareness of a public less familiar with musical artworks. [17]

Adorno set the standards for public discourse on music in the German-speaking countries of the West for several decades following the end of World War II. When currently speaking of a retreat, resignation, or replacement of music criticism, we mean music criticism realising Adornoian-type ideals. The debate that caused Adornoian-style theorising to lose its high ground was, by contrast, pursued in the musicological community. It may well be argued that culturally-turned reasoning about music on the one side, and a structural understanding of the artwork as “a self-enclosed and internally consistent formal unity” do not have to be irreconcilable. [18] However, even plausible arguments cannot turn back time in a history of ideas. The idea of a “breakdown of music as a discrete concept” has historicised and ultimately delegitimised any attempt to position music on a vertical axis ranging, as defined above, from the chthonic to the transcendental. [19]

Dahlhaus and the Decline of the Großkritiker

Without forgetting the belletristic vocation of one strain of music criticism and the role composers played as critical experts, a closer look at the relation between music criticism and musicology may elucidate cultural change processes affecting the role of music criticism. Musicologists also working as music critics have influenced the debate on music in many national cultures. One thinks of Boris de Schloezer, Armand Machabey, Henry Prunières, and Léon Vallas in France, for example, [20] and Ernest Newman, Edward J. Dent and Donald Francis Tovey in Britain. [21] In the German-speaking countries, Carl Dahlhaus may be considered the last great musicologist also working as a music critic. As a culture editor at the Stuttgarter Zeitung between September 1960 and November 1962, he published a total of 108 concert, opera, and recordings reviews. Miriam Roner has shown to what extent Dahlhaus’s work as a critic was based on the concept of the musical artwork. Given that the musical scores can be seen as underdetermined, and the musical performance, by contrast, as overdetermined, Roner states that “the work as an intentional entity has to be identified through the coaction of several different actors.” [22] Here again, as with Adorno, the musical artwork needs discourse to become fully discernible. It is in this sense that Dahlhaus aims at the “constitution of the artwork” (Roner) through his reviews.

Dahlhaus wrote his reviews from a position of supreme power. His texts let readers understand that the critic was in possession of a higher level of insight than both the musicians and the ordinary public, superior perhaps even to historical composers who in their time couldn’t have any cognizance of Wirkungsgeschichte, the history of reception and interpretation of their compositions as they became transformed into “works.” With a precise linguistic strategy, Dahlhaus shifts his reviews from the realm of “opinion” to what since Plato (politeia VII, 534a-c) has been considered the superior category: “knowledge.” The grammatical subject of his texts is neither “I,” nor “you”; there is no opening towards dialogue. Instead, Dahlhaus uses “one” as a subject, the German man, a generic subject assuming and presuming universal rationality and validity. [23]

While shedding light on Dahlhaus’s self-perception, the critic’s chosen role was far from being idiosyncratic. Twenty-five years later, Zygmunt Bauman would historicize it:

The typically modern strategy of intellectual work is one best characterized by the metaphor of the “legislator” role. It consists of making authoritative statements which arbitrate in controversies of opinions. … The authority to arbitrate is in this case legitimized by superior (objective) knowledge to which intellectuals have a better access than the non-intellectual part of society. [24]

Bauman identifies “to civilize” as the leading motive of modernity, an “effort to transform the human being through education and instruction.” [25] Nowhere else, following Bauman, has the educating and legislating role of intellectuals been so dominant as in the domain of art and art criticism, and nowhere else “[has] the authority of the intellectuals [been] so complete and indubitable.” [26] Although music is based on sensory experience, there is little evidence for many assertions forming music-related discourse. One way of resolving (or sugarcoating) the problem is to transform music criticism into a belletristic undertaking. Another solution consists in amplifying the role of the critic as a legislator. In this sense, leadingGroßkritiker (grand critics) have also been called Kritiker-Päpste (critic-popes) in the German-speaking countries. In synchrony with the paradigm shift from “modern” theorising, based on universalist assumptions, to “postmodern” ones, the use of the term Kritiker-Papst peaks in 1975 and falls into disuse after the year 2000. [27]

The (D)Evolving Role of the Intellectual

In opposition to the prima pratica of the “legislator,” Bauman posits the postmodern role of the “interpreter”: “With pluralism irreversible, a world-scale consensus on world-views and values unlikely, and all extant Weltanschauungen firmly grounded in their respective cultural traditions, … communication across traditions becomes the major problem of our time.” [28] Within Adornoian theory, Herder’s and Rousseau’s ideals of a common language for an inclusive mankind are still echoing, thus music and subsequently critical discourse is seen as addressing the whole of mankind, now understood as the self-emancipating subject of history. Conversely, the postmodern world outlined by Bauman is constituted by languages and groups. “What remains for the intellectuals to do,” in Bauman’s words, “is to interpret such meanings for the benefit of those who are not of the community which stands behind the meanings; to mediate the communication between ‘finite provinces’ or ‘communities of meaning.’” [29]

To understand the changing conditions of music criticism it is not sufficient to view universalist claims only as an intellectual problem. After all, Adorno’s Critical Theory was committed to building a new and better society. [30] Concerning poetry and song as living art forms, singer Thomas Hampson has drawn attention to what he, as a performer, perceives as an erosion of its humanist foundations. Assuming that the genre of song features the complexity of “being human,” Hampson deplores that “we do no longer understand the arts as a day-book or a textbook of existence,” and that “we” do not recognise “our vision of the world, our Bildungsprozess [formation/education/personal growth], our own self” in lyric art anymore. [31]

Clearly, the role model of the “legislator” had a structural affinity with the auctorial, one-to-many approach of what during the twentieth century was understood as mass media. [32] At the same time, “legislating”—i.e., making judgments on the basis of universal humanist assumptions—was at the heart of both the ethos and pathos of music criticism. The reasons negotiated in critical discourse on music were assumed to concern every person reading a general information newspaper, irrespective of their personal interests, just as political reporting, analysis, and comment are believed to concern every citizen. In many cases, “legislative” music criticism fulfilled functions similar to what Bauman, in line with the postmodern paradigm, called “mediation” and “interpretation.” Yet, this endeavour of promoting the understanding and appreciation of music continued to dwell and flourish on the assumption of artworks being an exemplary instance of the “self-encounter of man.” [33] Deprived of this assumption, or deprived of “man” (“Mensch”) as a category deemed to be of relevance, music criticism turned into a service for special interest groups or Bauman’s “communities of meaning.” Auctorial music criticism lost prestige and legitimacy in twentieth-century-type mass media and became subjected to the quantitative logics of audience share.

The Demise of Traditional Media

As effective as it might appear at this point to indulge in a narrative in which “the before” and “the after,” “the modern” and “the postmodern,” “old media” and “new media” appear as discernible entities, we will rather opt for distinctions made on a spectrum of differences, and attempt to account for the iterative, sometimes nonlinear and even contradictory changes in behaviour that in aggregate constitute what we interpret as cultural change.

Concerning the complex of media practices registering a loss of actors, we have to include the decreasing use of the medium in which music criticism has thrived in the first place. In 1936, Adorno described how “countless readers” resorted to their newspapers every morning wishing “to regulate their opinion” on what they had listened to the night before. According to Adorno, this behaviour was a normality, albeit an endangered one. [34] If we look at Germany today, the reach of printed newspapers and magazines has fallen from 60% in 2005 to 22% in 2020. [35] This tendency is confirmed by the European Commission’s statistics for the countries forming the European Union in the period from 2010 to 2019: the use of the older mass media such as television, radio, and most markedly the written press has been declining while internet-based media are on the rise. [36]

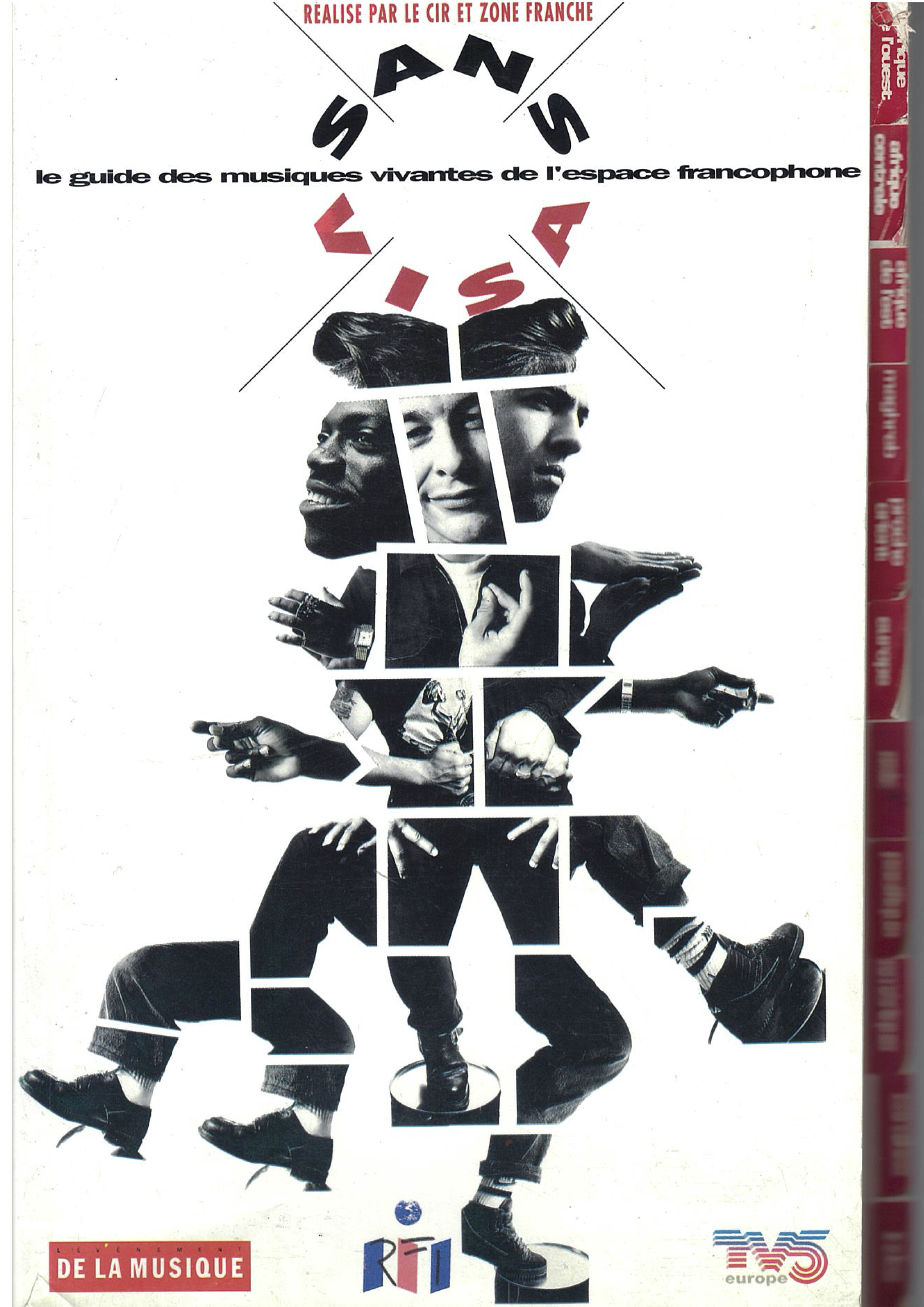

This widening use of internet-based digital media affects much of present music journalism, and the text on the evolution of French world-music journalism by Benjamin MiNiMuM and Angèle Cossée (see Appendix 2) may be read as a document for the iterative and often nonlinear adaptation and appropriation process in which “old” and “digital” media usages are interwoven, while innovative publishing strategies are increasingly pursued on the internet. Music journalism in digital media is mostly dedicated to the representation of musicians, musical activities, and products, in line with an understanding of the internet as an inclusive medium, characterised by “low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement,” a belief that “contributions matter,” and by a sense of “social connection.” [37]

MiNiMuM and Cossée’s work is one telling example of the representation of music cultures formerly outside the focus of music criticism in established media. Another example is Music in Africa (musicinafrica.net). The platform, founded in 2013 and “reaching millions of people every year,” [38] structures the representation and self-representation of musicians, producers, and cultural managers across the African continent. It features products and events, informs about technological developments and business opportunities, and offers reflections upon political and social conditions of musical practice. It also dedicates a whole section to the presence of women in African Music, discusses questions of music education, and proposes solutions for problems like those arising from the Covid-19 pandemic.

Evidently this is a major shift in the evolution of the mediatic presence of music-related discourse on this continent. Music in Africa performs a bundle of tasks previously unserved by mass media. In creating networks and channels of communication, it connects professionals and the interested public throughout the world. The platform establishes and facilitates information structures that transcend existing social structures anchored in local, regional, ethnic, or national communities. [39]

Internet and the Public Sphere

When it comes to music criticism stricto sensu, it may be asked whether the developments highlighted in the examples above merely represent a migration of practices and content from an older medium to a newer one, or whether there is a structural change under way that may alter the very definitions of music criticism. One might argue that the construction of the platforms is the expression of a target-group orientation and not much else. As an increasing number of people use the internet instead of print media, critics place their content there. Nevertheless, “target-group orientation” could also be interpreted as the result of a cultural shift from a “scholarly” stance to a “managerial” one, [40] and correspondingly a shift away from critics’ traditional role of custodians of artworks and associated values. In any case, the critical spaces presented in this issue of Sound Stage Screen have characteristic voids where more expert-based, “legislative” forms of discourse on music might be imagined. Reviews are mostly empathetic descriptions of what musicians produce, or statements about their self-perceptions, intentions, and public acclaim. In addition, the platforms feature factual information and explanatory texts about musical practices and local traditions. The reviews fall, however, short of the requirements traditionally associated with music criticism consisting of aesthetic judgments based on criteria. The explanatory texts for their part do not appear to be up to par with the standards of humanities research.

While print-based music criticism took part in what was conceived as “the public sphere,” multi-platform music journalism relates to something different that might be tentatively conceptualised as “specialised public spheres.” Why does that matter for music criticism? Bauman, while putting forward the idea of intellectuals as “interpreters,” does not seem to be concerned about the mediated nature of these new forms of engagement. His “communication across traditions” seems to presuppose a comprehensive communicative space in which processes of mediation between groups take place. [41] Lash and Urry later conceptualised the question in a multidimensional space. In this space the level of reflexivity is augmented by the proliferation of communication networks on the side of the structures, and by individualisation processes following the “retrocession of social structures” on the side of the actants. [42]

Both expectations were formulated at the very beginning of the rise of internet-based digital media. Today, there is an ongoing discussion whether we are witnessing the emergence of a worldwide participative and inclusive communicative space, or rather the fabrication of disruptive public spheres, and as to how far an expansion of meaningful reflexivity is taking place. Since conceptions of the public sphere depend on normative assumptions, every valuation here is literally a function of values. In this respect, Hans-Jörg Trenz has drawn attention to the tradition of thought leading from Kant’s programme of universal enlightenment to Habermas’s notion of a public sphere (Öffentlichkeit) that “unfolds in the individual and societal practices of reason” and therefore is “the method of enlightenment.” [43]

Habermas himself recently undertook an assessment of the change in media culture in light of his earlier theory, particularly The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere dating back to 1962. Habermas’s understanding of the public sphere as a field where the “peculiarly unforced force of the better argument” plays out, [44] and as an “inclusive space dedicated to a possible discursive clarification of competing claims on truth” may seem to have anticipated early ideas of an emancipatory internet. [45] Given the high stakes, Habermas, however, comes to “utterly ambivalent” findings today. [46] First of all, the blurring of the distinction between the “private” and the “public” produced by social media eliminates the inclusive character of a public sphere that used to be distinct from the private realm and thus favoured mediation between the single citizens and the system of politics. [47] The resulting fragmented, rather plebiscitary than deliberative „ demi-public spheres“ (Halböffentlichkeiten) often compete against others, producing “uninhibited discourses, shielded against dissonant opinions and critical comment.” [48]

It is true that Habermas is specifically interested in the political function of Öffentlichkeit, where citizens mediate between private interests and the common good, and reason emerges from cooperative deliberation. What makes Habermas’s theory of the public sphere relevant for music criticism is the fact that the aesthetic judgement, the judgement of taste in Kant’s Critique of Judgement, is of an equally public nature. If, following Kant, judgement “is the faculty of thinking the particular as contained under the universal,” the judgement of taste “with its attendant consciousness of detachment from all [individual] interest, must involve a claim to validity for all men. … There must be coupled with it a claim to subjective universality.” [49] Kant, in the middle of his abstractions, describes the act of the aesthetic judgement as a practice: “if upon so doing, we call the object beautiful, we believe ourselves to be speaking with a universal voice, and lay claim to the concurrence of every one.” [50] Carl Dahlhaus remarked that the judgement of artworks involves more than only Kantian judgements of taste. [51] But if we account for the moral judgements Dahlhaus includes in the judgement of artworks, the reference to a sphere of universal claims turns out to be further strengthened. One could therefore deduce that the disruptive effects of internet-based media on the efficiency of “the public sphere” as well as an insufficient “discursive quality” of contributions will affect the grounds and the development-paths of music criticism. [52]

Narratives of Cultural Change

At this point (if not before) it becomes apparent that argumentations based on historical grounds of music criticism have a tendency to become self-reinforcing if not circular. Music criticism has developed in institutional contexts and within dispositives based on assumptions about truth-conditions as well as the human condition. It has been integrated in narratives, inscribed in media systems, and incorporated in role-models that do only partially find their expression in the culture of internet-based digital media. As the historical resources erode, music criticism is on the wane. On the other hand, the impression that “Things Fall Apart” (Chinua Achebe) has been pervading the self-perception of modernity in the longue durée. It is not exclusively the expression of a transition from “modern” to “postmodern,” or from “old media” to “new media.” Friedrich Schlegel in his late essay “Signature of the Age” (1820) already deplored the “chaotic flood of opinions flying past.” [53] Hugo von Hofmannsthal in his Letter of Lord Chandos (1902) recounts deconstruction as an existential experience. Chandos discloses his state as “[having] lost completely the ability to think or speak of anything coherently. … For me everything disintegrated into parts, those parts again into parts; no longer would anything let itself be encompassed by one idea. Single words floated round me.” [54] And Adorno begins his Aesthetic Theory (1970) with the statement that “it is self-evident that nothing concerning art is self-evident anymore, not its inner life, not its relation to the world, not even its right to exist.” [55]

In order to contemplate alternative concepts not entangled in the legitimatory compulsions resulting from dichotomies between “the old” and “the new,” “tradition” and “progress,” “inertia” and “innovation,” we might choose to frame change as a continuum. Susan C. Herring, for example, has proposed to understand the evolution of media and genres as relationships shifting “along a continuum from reproduced [or familiar] to adapted to emergent.” [56] We could thus draw a line from the “familiar” text format of critical reviews to the “adapted” format of blogs. Blogs change their material manifestation as digital media simulate features of print. Otherwise, they continue to comply with the conditions of textuality. They continue trying to be coherent, cohesive, and consistent. They apply rhetoric strategies. “Adapted,” formerly “familiar” texts could then become “emergent” in the form of transmedia storytelling coalescing in multimodal digital artifacts.

Most of the debate on the “death” of music criticism is based on the dichotomic paradigm, such as William Deresiewicz’s recent lament about “the eclipse of expert opinion and the rise of populist alternatives: blogs, ratings, comment threads, audience reviews; Twitter, Facebook, YouTube.” [57] In contrast, theories based on the continuum paradigm may still be infused with disruption anxiety, but “death” does now appear as a transfiguration ranging from “remediation” (Bolter and Grusin) to “demediation” (Stewart). This paradigm accommodates most of the discussion about a “future” of music criticism. [58]

Singularised Actants and the Grounds of Judgement

With all its inherent wisdom, however, a theorising continuously mutating identities and practices is good at differentiating but not very effective with regard to distinction. Another aspect of the phenomenon becomes discernible if we think change in the mediality of music criticism as a disruption. Firstly, as a disruption in terms of intellectual history. Here we might put into practice what Jean-François Lyotard stated in The Postmodern Condition: “abandon the idealist and humanist narratives,” increase the distance to the “obsolete … principle that the acquisition of knowledge is indissociable from the training ( Bildung) of minds, or even of individuals.” [59] This mostly concerns the sociological perspectives of media theory. Secondly, from a technological point of view, networked digital media may not be understood as “new media” adding new functionalities to existing media, but as an emergent phenomenon, as categorically distinct “hypermedia.” These hypermedia may simulate and thus preserve prior physical media. Beyond that they also give rise to “a number of new computational media that have no physical precedents,” [60] thereby generating modes of reflection that prior to their emergence did not exist.

Concerning the sociological dimension of media disruption, Elizabeth Dubois and William H. Dutton conceptualised the emergent entity as a “Fifth Estate”:

As such, the Fifth Estate is not simply a new media [sic], such as an adjunct to the news media, but a distributed array of networked individuals who use the Internet as a platform to source and distribute information to be used to challenge the media and play a potentially important political role, without the institutional foundations of the Fourth Estate. [61]

Who are these “individuals” acting on the platforms? It can be doubted whether they coincide with the citizens Habermas has in mind as communicators in the discoursive public sphere. Nor do they correspond to the emancipatory subject Adorno evokes when reflecting upon music criticism. Digitally networked individuals fall short of enacting the dialectics between the particular and the general, the individual and the universal, or the subjective and the objective as implied in Adorno’s warning against a deterioration of criticism induced “by the shrinkage of a subjectivity that mistakes itself for objectivity.” [62]

These “individuals” populate the platforms and make use of their single-agent broadcasting (webcasting) capabilities. What is more, they appear as products of the platforms themselves and of their underlying algorithms. Crispin Thurlow criticises that “the affordances and typical uses of social media foster a microcelebrity mindset of extreme self-referentiality.” [63] Andreas Reckwitz has integrated observations of this kind with pre-internet discussions about “Modernity and Self-Identity” developing a comprehensive theory of the “late-modern self” and its systemic collocation in a “post-industrial economy of singularities.” [64] In this economy, digital technologies gain significance as a “general infrastructure for the fabrication of singularities.” [65] This singularisation is at once a product of the interaction between persons, between persons and machines, and—in the computational deep structure of the platforms—of interactions between machines. Social media “with their profiles are one of the central arenas where the elaboration of singularity takes place.” [66]

For the one thing, this “singularity” is a performative category. “Singularity” is the (ephemeral) quality of communicative artefacts that prove successful on “attention markets.” [67] This, incidentally, might help explain how trending topics unseat canon. At the same time, “singularisation” is an ongoing process of predications, judgements, and negotiations of judgements. Formally, these judgements—Reckwitz calls them “valorisations”—put the particular or “the idiosyncratic” into a relationship with schemata of the general. [68] In linguistic practice, these judgements rather look like assignments of subtopics to superordinate terms. To generalise, Reckwitz states that in late-modern societies a structural transformation is taking place that causes “the social logic of the general to lose its supremacy to the social logic of the particular.” [69]

As “subjective universality” ceases to serve as the reference point of judgements, Kant’s “judgement of taste” loses its base. Opinions on the aesthetic value of objects and performances evidently continue to be expressed in the “postindustrial economy of singularities.” On social platforms they are proliferating. But from a Kantian perspective they are just that: private opinions about the effect of aesthetic artefacts “upon my state so far as affected by such an object.” [70] In a Kantian world, private opinions of the above kind do not contribute to public discourse; in this sense they are insignificant. Can this result in anything else than the liquidation of music criticism defined as a contribution to a public discourse based on arguments that can be discussed in turn? Hartmut Rosa still distinguishes between the “public opinion” (based on deliberation), and the preliminary realm of “private opinions” made public trough their aggregation in surveys and polls. [71] In a world, however, where “likes” are structurally integrated in the interface of digital media, expressions of personal pleasure or displeasure do not only have an effect on public opinion, but they also constitute it in a non-argumentative, stochastic way.

Strange enough, the authorities of the late bourgeois world of “legislators,” the ones declared historically obsolete by Lyotard and Bauman, are now reappearing on our digital media stages in the shape of “creatives” and influencers. Their audiences accept them as “experts” on the base of attributions and identification, less so on the base of acquired professional or academic competence. Yet that may, on closer inspection, also be said about some of the former “grand critics.” And possibly there is more continuity than might be expected considering the change in the fundamentals of critical practice. During the preparation of this article, I found little evidence of a significant shift in critics’ practices. Traditional critics embracing digital media mostly seem to limit themselves to moving their analogue texts to the equally textual blog, all the while continuing to make the “personal” perspective of their judgements more marked. Instead of using the collective subject “one,” dear at one time to Dahlhaus as a music critic, they now write “I.” Established music critics proved disinclined to give an account of their attitudes, practices, and experiences with digital media. Managers of major European concert houses, asked whether they could recommend younger content creators advancing discourse on music in digital media, replied, “tell me, should you find one.”

It may be understandably difficult for reasons of professional identity to move from one role model to another, or to give up the role model of a competence-based author in order to become a performance-oriented content creator. Few will manage to embody both roles. On the other hand, there are examples in neighbouring disciplines suggesting that new forms of singularising or singularised judgements can work for specific, potentially vast audiences. BookTok, the fast-expanding submarket of TikTok dedicated to appraisals (rather than reviews) of books, could be an example of a new form of criticism. Invent OperaTok. [72] Finally, the appearance of “grandfluencers,” senior netizens who gain audience as influencers presenting their mature singularities, proves that there is no age limit to the appropriation of role models developed through digital media. [73]

The Knowledge of Hypermedia

Hypermedia have disrupted the mediatic conditions for traditional music criticism. Differently from our everyday interpretation of change as bringing something “new,” both adding to and opposing the “old,” the concept of hypermedia theorises networked digital media as emergent, thus not incremental and not prefigured in existing media. If in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries media were “defined by the techniques and representational capacities of particular tools and machines” (materials could be added), digital media on networked computers now become simulated through algorithms and programmes. [74] This not only leads to multimodality, the merger of semiotic resources and modal affordances through a unifying code allowing for new modes of signification. It also makes the creation of meaning possible through the code (or “software”) itself. “Turning everything into data, and using algorithms to analyse it changes,” in Manovich’s words, “what it means to know something.” This emergent “software epistemology” implies the generation of knowledge and of “additional meanings” through the analysis of old data derived from analogue sources and of specifically generated data, and the fusion of separate information sources. [75]

Reckwitz mentions comparison technologies as part of the digital infrastructure of singularisation. [76] Applied to our case, this could mean programming portals able to automatise and edit the comparison of performances, a central genre of twentieth-century music criticism. Once successfully working on the base of recorded data, an application of this kind could also analyse live performances and thus create real-time reviews of musical performances based on objectifiable and negotiable criteria. Such a machine would certainly adopt known interpretation parameters, but the logic of data analytics implies it would also generate new criteria and parameters, new modes of reflection beyond our familiar semantic patterns of interpretation, beyond subjective experience coupled—deepened—with reflection. [77] Either way, the traditional sequence of a sonic event followed by a reflection in written form is no longer imperative from a technological standpoint. The very institution of the author, constructed in parallel with the figure of the composer, has been made optional by technological change. Given that texts are collectively shareable, why shouldn’t they be edited collectively for the purposes of debate? And do we need authors when it will be possible to link analytic software with automated social actors such as bots? [78]

Multimodality alters the conditions of language as the medium—in the large sense—of music criticism, while data analytics will influence the questions asked and the issues addressed. Network theoreticians have begun to look back on printed language as a kind of historical medium useful for some sort of pleasurable expression but fraught with capacity constraints. [79] While Habermas hopes users of social media may yet familiarise themselves with the role of authors and learn how to communicate in constructive ways, [80] these users already explore the ludic discursive practices of social media. In our daily practice we adopt heteroglossia through a hybridisation of idioms of written and spoken language. [81] We create texts combining written language and iconic elements. This is a language change many people embrace.

“Extraordinary Words”

Instead of (by all means plausibly) interpreting present language change from the perspective of cultural conservatism as an instance of regression or decay, people wishing to express themselves on musical matters could embrace the creative potential offered by digital media. Charles Dill and Stephen Rose have pointed out to which extent the evolution of music-related discourse in France and in Germany during the late seventeenth and the early eighteenth centuries was encouraged by a general interest in the cultivation of language. Vernacular languages, as opposed to Latin, then still the language of church and science, were further sharpened and refined as a means for sharing knowledge of musical practices and articulating aesthetic judgements, catering for a growing public seeking orientation through music-related discourse. [82] In essence, the much criticised “affective politics” of networked digital media, [83] their structural propensity to fuel antagonistic utterances and to polarize discourse, corresponds to a pattern that has structured a great part of critical discourse for well over 200 years, from the Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns through the disputes between imitation of “outer” versus “inner nature,” “melody” against “harmony,” “Wagnerians” against “Brahmsians,” “British” versus “continental,” “tonal” against “atonal,” up to “romantic” versus “historical” performance practice. Stephen Rose spoke of “the waspish nature of early musical criticism.” [84] Today, networked digital media offer historically unprecedented structural opportunities for fruitful and unfruitful public debate, and where those media divide, they can also connect and federate.

It was the paradoxical passion of those who wrote reviews of musical performances to express in words that which resisted language through indeterminacy. Whether or not one believed that the essence of music should be ineffable, the horizon of what was currently expressible served as a “liminal figure of immanence.” The effort itself to surpass the limit by writing a text constituted the critical subject, just as the perspective of subjectivity was already incorporated in the concept of horizon itself. [85] While it is possible to perpetuate this effort and experience, the language of the subjective—the language of the self-emancipating subject of history, the language of public oratory, all of which used to be music critics’ preeminent medium—has lost its status of reference point for many users of digital media. Hence music criticism based on arguments—and heroically (and sensually) grappling with the limits of the expressible—has become a language game making use of what J. L. Austin once called “extraordinary words,” not unlike the language games associated with wine tasting or spiritual epiphanies. [86]

What is lost, after accounting for possible exaggerations of retrospective idealisation, merits to be mourned. Eventually, the decomposition of a culture of deliberation or even the public sphere as a whole would endanger much more than just music criticism. However, Lyotard has defined Wittgenstein’s invention of the language game precisely as an endpoint of a historical mourning process as it creates a kind of “legitimation not based on performativity.” It relieves expression and communication from the onus to legitimate what cannot be universally legitimated through language anymore. This is a process of both unlearning and learning. Lyotard concludes: “Most people have lost the nostalgia for the lost narrative.” [87]

Protracted Practices and the Communicative Space of Vital Issues

So does the question of music criticism in the age of networked digital media end up in a wilderness, in an inextricable entanglement of genesis and demise, progress and regression, assertion and oblivion? In the last chapter of the History of Music Criticism, Christopher Dingle and Dominic McHugh claim that “music criticism will continue“ almost no matter which changes affect its fundamentals and conditions: “Whenever and wherever music is made, in whatever genre, there will be those who wish to discuss, describe and debate it, argue, attack or advocate it, read, reflect and write about it in whatever medium is available.” [88] This is probably true, and also a bit less than that, a truism. It integrates the psychological motives of music criticism into a cultural system of practices. As long as this system exists, opinions on music will be expressed and published howsoever. As long as there are children learning to play the guitar and the clarinet, as long as singers embody historical anthropologies, as long as someone attends concerts identifying herself with the musicians and their effort, as long as someone contemplates musical artefacts by listening or reading, discourse may follow. Viewed under this light, music criticism will not survive, rather it will continue to be. Music critics writing reviews will become an anthropological symbol just like musicians with their premodern bodily crafted modes of production. The achievements of networked digital media will guarantee the persistence of music criticism as we knew it, provided that the global databases fulfil their promise of storage and retrievability. Music criticism will find its place in the long tail of ideas.

What Dingle and McHugh do not account for is the institutional dimension of music criticism. This is, though, where the problems lie. While a history of music criticism as an institution has yet to be written, Stephen Rose, Mary Sue Morrow, and Charles Dill provide valuable information about the process of institutionalisation in Germany and France until about the year 1800. The overall impression is one of a vibrant, manifold debate, and of an effervescent will to go public with reflections on musical execution, expression, aesthetics, and taste. Morrow, however, has also raised the issue of “continuity and the critical mass of opinion necessary for the formation of a thought collective,” [89] problematising the fact that most publications encouraging and collecting critical contributions were short-lived. The problem seemed to have been resolved in the twentieth century. By then, music criticism held a secure spot in generalist one-to-many media that purported to cover the universe of topics of general interest. Today, as the emergence of networked digital media is lessening the importance of the older generalist media model and contributing to what is perceived as a fragmentation of the public sphere, Morrow’s historical question of “continuity and the critical mass of opinion” is inverted. In the eighteenth century, the development of a federating media structure lagged behind the desire for a continuing public debate. Today, technological development may be too rapid to allow emergent media practices to become both common and entrenched.

Can music criticism thrive meaningfully in a fragmented public sphere with no medium to represent music-related discourse relevant for a general public? Does music criticism have to be an institution at all? Of course, it does not—who, after all, should request it? Resorting to the wisdoms of renunciation is always an option. However, certain questions open up one path out of the secular stagnation of the music-related generation of sense. It was the desire of a public to collectively know and discuss which constituted the unity of the multifaceted eighteenth-century reasoning on music, while the development of a federating ecology of media was still under way. The public’s music-related-questions were of general interest, as Morrow, Rose, and Dill have shown. They were linked to personal growth and development, the right way of becoming a person of feeling, the right compositions to buy and study now that a fortepiano or a flute had been acquired for one’s household. They were also questions about national character, questions of morality and taste. Common interest questions, rather than media, also constitute the discourse space in which Bauman’s communication between groups and intellectuals acting as “interpreters” can take place, and sense can be produced along shared axes of relevance.

What are then the common-interest questions raised by music critics today? What new questions are emerging from the current music scenes? Can music be associated with vital issues, issues that bring together people from various walks of life? Can music-related discourse help construct one’s singularity just as it served to develop people’s subjectivity fifty years ago? What are the questions brought to the fore by social media? What will the questions generated by data analytics look like?

Should all our listening be in vain, should big questions related to music fall silent, the long tail of ideas will continue to offer a place for sumptuous remainders, rearguard battles, and special interest discussions. Should new questions make themselves heard, music criticism will survive, ceasing to continue to be what it was.

The Spirit Lost: Music Criticism and the State of Art Music

Peter Uehling (Berlin)

(English translation by Klaus Georg Koch and Alexa Nieschlag)

Why do I still practise my profession as a music critic? Apart from obvious material reasons, I do not know. It is not necessary to exaggerate the question at stake the way music-philosopher Heinz-Klaus Metzger does, claiming the continued existence of humankind depend on us listening more to music from John Cage. However, the impression that serious music seems to be right about nothing anymore does look by all means like an apocalyptic mark on the horizon.

My perplexity is being raised and nourished by three elements. The first is part of the general crisis of education and cultural knowledge which, for its part, is a crisis of the primary text. People do not read any more. Even in university classes students do no longer study historical texts in an aesthetically adequate way. At best these texts deteriorate into information about past states of civilization and ideologies. More likely they do mutate into mere rumour following the fact that only their secondary meanings are being perceived. As far as music is concerned, this process of deterioration is somewhat different in that music is now only perceived in terms of personal pleasure and displeasure.

In both regards the result is the same: the canon disintegrates. The want for entertainment, rehearsed through hundreds of channels, first dissolves the propensity to perceive and then goes on creating petty idiosyncrasies, vulgo “filter bubbles,” that finally become compacted by algorithms.

The second, more specifically musical of the three elements seems to contradict the first one. The quality of professional musical training and of practical skills is increasing, seemingly without any limits. More and more extremely skilled musicians appear on the stage, unhampered by technical difficulties. This has certainly made the work of orchestras more efficient, if we want to overcome the unease brought along by the use of a concept like “efficiency” in the context of the arts.

The effect of such an efficiency unhampered by technical limits is a distinctly strange emptiness. Practically every professional orchestra is now able to adequately perform works like Strawinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps or Alban Berg’s Drei Orchesterstücke. Virtually every string quartet excels at dissolving the problems of consonance into mellifluous sound. Neither the piano works of Chopin, Liszt, or Rachmaninow nor Bach’s pieces for violin solo pose any serious challenge to contemporary soloists. However, if all technical difficulties posed by musical works, by instrumentation or instrumental technique are resolved, then a formerly constitutive “frictional surface” is lacking, or perhaps an intermediate void calling the interpreter’s mediation between what used to be utopically technical or technically utopian on the one side, and the meaning of a work on the other. Today, such mediation seems to be no longer necessary since the artwork is becoming entirely realized in its appearance. And yet something is missing. We might call it, boastfully and ineptly at the same time: Spirit.

What is lacking to the instrumentalists, and here I am approaching the last of the three perplexing elements, is the challenge that from the Baroque until the times of Strawinsky and Strauss used to be posed by contemporary music. Instead, a death certificate may be issued confidently for the contemporary music of our days. Contemporary music has disappeared from the public sphere of our concert halls only to be given artificial respiration in the intensive care stations of dedicated festivals. Any influence on the culture of our time has been lost. What is occasionally performed in subscription concerts serves the organisers as evidence they are taking their responsibility for the presence of “serious music,” a music in which the very organisers do not believe any more.

There are no more composers left who would be present in both concert halls and specialized festivals. A first group of composers supplies symphony orchestras with dreary sound games whose modesty in terms of instrumental technique proves the fact that no musician and no concert-institution is willing to engage in extended rehearsals. The others have been stranded at conceptual work while striving for novelty in music. “Concept,” unfortunately, is usually just another word for “free association,” associations that do not require any aesthetic perception because in the end there will be a punchline suitable to be carried home as a certain insight. Here we are back to the general crisis of education and cultural knowledge mentioned before.

Serious music thus does not pose any challenge to the public sphere anymore, and it ceased influencing public discourse productively. It is being rightly asked why society should spend any more money on this kind of cultural practise.

Making observations like these at a personal age over 50 one is well advised to critically ask oneself whether perceptions are not the result of any déformation professionelle or due to nostalgia. Perhaps the analysis presented above is based on standards and canons valid only 30 or 40 years ago?

To begin with, it isn’t plausible either to assume youthful enthusiasm could provide more reliable insight than a thoroughly aged distanced view. And of course music continues to thrill me as a private person—as long as it isn’t the music played in concert halls. Even if the parameters of my analysis should be “historical” by now: we are also dealing almost exclusively with historical art forms and historical institutions.

How should we value in this context the nomination of Kirill Petrenko as chief conductor of the Berliner Philharmoniker? Many claimed at the time this was meant as a kind of turn towards “art” after the era of Simon Rattle with its impact mainly on organisational matters. What would, however, “artistic turn” mean? Rattle had delivered his recording of Beethoven’s symphonies pretty much in duty bound. Petrenko may be of a different caliber in terms of fanaticism and vivification, but this does not alter the fact that no one is actually longing for a new recording of Beethoven’s symphonies. The same can be said about the symphonies of Josef Suk Petrenko is very interested in. It is not wrong to play these compositions but on the other hand playing them is an entirely irrelevant act, just as it doesn’t make any difference whether an orchestra does play symphonies of Ralph Vaughan Williams or Bohuslav Martinů. Playing music like these has been an evasive maneuvre for more than half a century now, just as performing a new work of Jörg Widmann today is an evasive maneuvre meant to get around postwar modernism whose works are less handy to perform.

This is by no means to claim that our musical life receive a stimulating energetic impulse did music from Boulez, Stockhausen, and Nono regularly appear on our subscription concert programmes. Basically, this music is not performable and out of place on a concert stage, right as it would be the case with music of the Renaissance on the opposite side of history.

The reintroduction of works by Suk, Rachmaninow, Vaughan Williams, and their traditionalist colleagues tells us one thing: music from the twentieth century is by far not as atonal as the Second Viennese School’s PR-departments were claiming. And the very transient effect of these restaged compositions is a proof of the fact that the artistic topicality of this concert-hall-music is actually a thing of the past. This out-of-dateness was obscured by the Mahler-renaissance which did for one more time change our ideas about the concert repertoire. Yet Suk and the likes do not dispose of this very potential, and Mahler’s has been depleted.

Our concert halls and symphony orchestras have reached the end of the line, and so has a splendid repertoire that went from Beethoven to Strauss. Modernity, which had got its bearings by the celebration of musical autonomy, croaked from that very idea or ideology. However, this idea of autonomy has always been belied by the fact that “autonomous” music did need a demand, a demand for national or highbrow middle-class self-assurance, for noble emotions as well as for scandals. A music free from any demand by listeners, musicians or institutions may be imaginable. Its fate is foreseeable as well. (The same can be said, by the way, of string quartets that have lifted the ideology of autonomy to tremendous heights. They now get broken by the very limited repertoire of always the same compositions by Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Brahms, and Bartók.)

To say it clearly: listening as a form of reception holding the same dignity as reading literary texts and looking at paintings, sculptures, and films has had its place within the concept of autonomy of music, nowhere else. The fact that only few were able to realise this kind of perception in its fullest sense has encumbered what had been called “absolute music” with misled respect and perverted it into those functions of distinction described by Pierre Bourdieu. It may be interesting in this context that the first concert being immediately sold out in the Berliner Philharmoniker’s 2022/23 season was the one in which film composer John Williams directed his own works. This may be excused as an exception, and the public in this case was not the usual one. On the other side this programme worked very much the same way the usual symphonic programmes do. Revolving within and around themselves they are speculating on the same effect as the well-known film melodies. Listening on this level does mean to recognise. However, while John Williams is speculating on this effect legitimately, based also on the leitmotiv-effect accompanying a film, in the case of a Beethoven symphony recognition as a receptive attitude does mean a distortion of the composed matter. Here recognition of musical elements would have to be reflected upon their function in the course of the musical process. In other words: the emotional effect of recognition should be accompanied by perceptive insight.

Whereas in “absolute music” a historically unique high ground may have been reached, the according symphonic and chamber music is not the only paradigm, and the contemplative combined with analytic listening is not the only valid reception mode. Looking at opera and music theatre the situation does not appear entirely daunting. Being linked with action on the stage, opera is at least free from the lie of autonomy. For the moment, German Regietheater is still rather self-referential but it can be expected that the mostly sacrosanct orders codified in the scores will be disbanded, and this is going to release a new boost of creativity allowing for new insights into the repertoire. Of course this prospect may be a frightening one as well.

First and foremost, the human being that sings will remain an unpredictable entity of ineradicable individuality and limited perfectibility, as opposed to the drilled instrumentalist. Her and his charisma extends as far as into a form in which reception and production mingle with each other: choral singing. Certainly, in this realm, too, pseudo-expert bigotry may be cultivated. However, in many cases choirs do create a bond with tradition which can then be carried forward into our present by committed choirmasters. There are, thus, semiprofessional choirs of astonishing musical quality singing surprisingly contemporary programmes. Even if their concept of contemporary music may comprise music different from the one performed by specialised formations for contemporary—“Neue”—music, they are connected to newer tendencies proclaiming the end of the development of musical material and the use of music that is already present. It is understood that due to the necessarily longer production cycles these semiprofessional choirs get into closer contact with their compositions, compared to specialised formations scheduling only one and a half rehearsal-units for a first release. Thanks already to the time invested, these works acquire more value than any of the world premieres produced by Ensemble modern. Perhaps “value” in this case is no longer attributed based on aspects of “autonomy” but this does only stress what music is more than anything else: a social life event.

How does now music criticism relate to all this, given that the genre did evolve alongside the ideology of autonomous music? Whereas music criticism in the perspective of autonomous music tried to make the heard understandable to the non-expert citizen, contemporary music critics will notice that they are writing for readers who are not driven by the desire to get music explained. Often enough they tediously remark the critic must have attended a different concert than their one, so the question may be raised: Why someone seemingly sure of their judgements do read a review at all?

Music criticism does not want to “know it better.” Instead, it wants to widen readers’ aesthetic criteria and perspectives. In this sense, music criticism does not occupy any position of authority one might consider as “microaggressive.” Whoever does attribute authoritarianism to it does not want to learn anything other than what he or she does—or does not—know. In other words, rejecting the mission of music criticism would mean abandoning the “culture of discourse” for a “culture of dispositions.” According to Markus Metz and Georg Seeßlen, [90] in this identity-oriented culture the much-praised ambiguities distinguishing a “culture of discourse” do vanish.

Admittedly, it is no use stemming oneself against change in the field of aesthetics as if one could clamorously call back former states of things. Naming again and again the powers that unmade the past, lamenting the consequences would, in the long run, be tedious and insubstantial. On the other side, who would claim in earnest that advertising ever fresher virtuoso-meat might be anything more than to commercially exploit new faces? The few old virtuosos left aren’t being dethroned by the young ones. The contrary is the case: Martha Argerich and Daniel Barenboim, to make two examples, seem to continue to ascend Mount Olympus, all the more so compared to the short-lived careers of their young counterparts. The farcicality of the business does, however, concern both camps. The felicitations and good wishes accompanying the emergence of new talents onto the scene is no less ridiculous than the apotheosis of a virtuoso featuring an absurdly shrunk repertoire or a conductor lacking any concept of interpretation that transcends brilliant, nineteenth-century-style “witchcraft.” Both Argerich and Barenboim, differently from what can be supposed of the young virtuosos, still do have an idea of what “art” is, unfortunately rendering obvious the degree of helplessness a concept acquires once it has fallen out of time.

What is then left to be written? It seems astonishing and hardly understandable any longer which remarkable degree of status music criticism once could have and did have. In our days, the big questions of society pose themselves more immediately and urgently and perhaps request solutions in a more concrete way. This does change the climate not only for aesthetic reception but also for (re-)production. Every production must prove its relevance, on the lowest level (John Williams) its entertainment value, on a slightly higher level its societal wokeness (female composers, music forbidden by the Nazi regime etc.). But even if it may seem hard: music criticism does not only have to make up the balance of what has been lost and long for better times.

Had it once to decipher what “autonomous art” did tell about and tell to society, the task is nowadays to explain in which ways socially-oriented artistic production might still be emphatically art. Back then, as well as today, the challenge is to sensitise and enhance aesthetic perception thus relating and linking art and world.

****

Warum ich meinen Beruf als Musikkritker noch ausübe – von den offensichtlichen materiellen Gründen abgesehen –, weiß ich nicht. Man muss nicht gleich übertreiben wie der Musikphilosoph Heinz-Klaus Metzger, der behauptet hat, der Weiterbestand der menschlichen Zivilisation hinge davon ab, dass wir mehr Musik von John Cage hören. Aber dass es nun in der ernsten Musik tatsächlich um gar nichts mehr zu gehen scheint, hat durchaus etwas von einem apokalyptischen Zeichen am Horizont.

Drei Momente sind es, die meine Ratlosigkeit verursachen und nähren: Das erste bewegt sich im Rahmen der allgemeinen Bildungskrise, die eine Krise des primären Textes ist. Es wird nicht mehr gelesen, auch im Studium werden historische Texte nicht mehr in ästhetisch adäquater Art und Weise rezipiert, sie verkommen bestenfalls zu Informationen über vergangene Ideologien und Zivilisationsstände, wenn sie nicht zum Gerücht werden, weil nur noch der sekundäre Abhub wahrgenommen wird. In der Musik ist dieser Degenerationsprozess anders gelagert, indem sie nur noch einem krud-individuellen Ge- oder Missfallen nach wahrgenommen wird. Das Ergebnis ist in beiden Fällen das Gleiche: Der Kanon zerfällt, weil das durch hundert Kanäle eingeübte Unterhaltungsbedürfnis zuerst die Rezeptionsbereitschaft zersetzt und dann belanglose Idiosynkrasien – vulgo Filterbubbles – schafft, die der Algorithmus weiter verfestigt.

Das zweite Moment scheint dem ersten zu widersprechen und ist musikspezifischer: Die Qualität der Musiker-Ausbildung verbessert sich in technischer Hinsicht anscheinend ohne Grenzen. Immer mehr technisch höchstqualifizierte Musiker erscheinen auf der Bildfläche, für die es keine Schwierigkeiten mehr zu geben scheint. Das hat die Arbeit der Orchester effizienter gemacht. Vom Unbehagen, im Zusammenhang mit Künsten von „Effizienz“ zu sprechen, abgesehen, entsteht dadurch ein ganz seltsames Vakuum. Wenn die technischen Schwierigkeiten eines Werks (wie des „Sacre du Printemps“ oder der Drei Orchesterstücke von Berg), einer Besetzung (alle Streichquartette sind mittlerweile in der Lage, die klanglichen Probleme in reinen Wohllaut aufzulösen) oder eines Instruments (weder die Klavierwerke von Chopin, Liszt oder Rachmaninow noch die Violin-Soli von Bach bereiten heutigen Solisten ernsthafte Probleme) gelöst sind, dann fehlt eine Reibungsfläche, in die früher gewissermaßen der Interpret einsprang, um zwischen dem technisch Utopischen und dem Sinn eines Werks zu vermitteln. Heute ist derlei Vermittlung nicht nötig, wenn sich das Kunstwerk restlos in der Erscheinung realisiert – aber irgendwas fehlt dann doch; man könnte so großspurig wie unbeholfen sagen: der Geist.

Was den Instrumentalisten fehlt – und damit komme ich zum dritten Moment – ist die Herausforderung, wie sie in der Zeit vom Barock bis zu Strawinsky und Strauss die jeweils neue Musik darstellte. Unserer heutigen neuen Musik jedoch kann man getrost einen Totenschein ausstellen. Aus der Öffentlichkeit der Konzertsäle ist sie verschwunden und wird auf den Intensivstationen der Festivals künstlich beatmet. Einen Einfluss auf die Kultur hat sie nicht mehr. Was im Abonnement gelegentlich erklingt, dient dem Veranstalter zum Nachweis seiner Verantwortung für eine Gegenwart der „ernsten Musik“, an die er selbst nicht glaubt. Es gibt keine Komponisten mehr, die zugleich auf Festivals und im Konzertsaal präsent sind. Die einen beliefern die Sinfonieorchester mit öde zu hörenden Klangspielen, deren technische Anspruchslosigkeit spiegelt, dass sich kein Musiker und keine Konzert-Institution wirklich dafür mit verstärktem Probenaufwand engagieren will. Die anderen sind auf der Suche nach dem Neuen beim Konzept gelandet, und „Konzept“ ist in der Regel nur ein anderes Wort für freie Assoziationen, die, und damit schließt sich der Kreis zur Bildungskrise, keinerlei ästhetische Wahrnehmung erfordern, weil sich am Ende eine Pointe finden wird, die dem Hörer als eindeutige und gesicherte Erkenntnis auf den Heimweg mitgegeben wird.

Die „ernste Musik“ stellt somit für die Öffentlichkeit keine Herausforderung mehr dar und wirkt daher nicht mehr produktiv in den Diskurs herein – zurecht wird daher immer vernehmlicher gefagt, warum man sich derlei Institutionen überhaupt noch leisten will. Wenn man so etwas als Mensch über 50 wahrnimmt, muss man sich immer skeptisch fragen lassen, ob man den Täuschungen einer déformation professionelle oder gar denen einer subjektiven Nostalgie unterliegt, ob man eventuell nach den Parametern von vor 30 oder gar 40 Jahren bewertet. Zunächst ist nicht einzusehen, warum jugendliche Begeisterung ein wahreres Bild der Verhältnisse transportieren soll als eine über die Jahre gewonnene Distanz; und natürlich begeistert mich privat Musik noch immer und tendenziell immer mehr (allerdings kaum noch die Musik der Konzertsäle). Und selbst wenn die Parameter der Bewertung historische sind: wir sprechen ja auch mittlerweile ausschließlich über historische Kunstformen und Institutionen. Wie ist zum Beispiel die Besetzung des Chefdirigenten der Berliner Philharmoniker mit Kirill Petrenko zu bewerten? Es war zu lesen: Nach der vor allem in organisatorischer Hinsicht bedeutsamen Zeit mit Simon Rattle soll es jetzt wieder um die Kunst gehen. Was soll das genau heißen? Schon Rattle hat seine Beethoven-Gesamteinspielung eher pflichtschuldig abgeliefert. Petrenko mag da ein anderes Kaliber an Fanatismus und Belebung sein – aber das hilft ja nicht darüber hinweg, dass niemand mehr wirklich auf eine neue Beethoven-Gesamteinspielung wartet. Genauso wenig wartet man allerdings auf die Symphonien von Josef Suk, für die sich Petrenko interessiert. Es ist nicht verkehrt, diese Stücke zu spielen, aber irgendwie ist es auch vollkommen egal, ebenso wie es keinen Unterschied macht, ob man die Symphonien von Ralph Vaughan Williams oder Bohuslav Martinů spielt oder nicht spielt: Das sind seit mehr als einem halben Jahrhundert Ausweichmanöver vor der Nachkriegsmoderne, die eben nicht so flott aufzuführen ist wie ein neues Werk von Jörg Widmann.

Ich möchte nun keineswegs behaupten, dass das Musikleben einen belebenden Energiestoß empfinge, wenn die Musik von Boulez, Stockhausen und Nono regelmäßig auf den Spielplänen des Abonnements erschiene, denn im Grunde ist diese Musik im Konzertsaal bereits so fehl am Platz – und oft gar nicht aufführbar –, wie es auf der anderen Seite der Geschichte die Musik der Renaissance wäre. Die Wiederaufführung von Suk, Rachmaninow Vaughan Williams und ihrer traditionalistischen Kollegen lehrt eines: Das 20. Jahrhundert war längst nicht so atonal, wie es die PR-Abteilungen der Wiener Schule behaupteten. Und die sehr vorübergehende Wirkung dieser Wiederaufführungen ist der Beleg, dass die künstlerische Aktualität der Konzertsaal-Musik tatsächlich vorbei ist. Das wurde über ihre Zeit hinaus durch die Mahler-Renaissance verdeckt, die noch einmal unsere Begriffe des Repertoires verändert hat. Aber Suk und die anderen haben dieses Potenzial nicht, und das Mahlers ist ausgeschlachtet.

Die Konzertsäle, die Sinfonieorchester sind am Ende und mit ihnen ein stolzes Repertoire von Beethoven bis Strauss sowie eine Moderne, die sich an der hier zelebrierten Idee autonomer Musik orientiert hat und an dieser Idee oder Ideologie krepiert ist: Dass auch die „autonome“ Musik eine Nachfrage braucht – nach nationaler oder bildungsbürgerlicher Selbstwertversicherung, nach hehren Gefühlen, aber auch nach Skandalen – hat ihre Autonomie immer Lügen gestraft. Eine wirklich ohne jeden Bedarf von Hörern, Institutionen oder Musikern hergestellte Musik ist vielleicht vorstellbar – aber ihr Schicksal ist absehbar. (Ähnliches gilt übrigens auch für das Streichquartett, das diese Autonomie-Ideologie in ungeahnte Höhen gesteigert hat. Die Ensembles gehen kaputt am ewig gleichen, sehr kleinen Repertoire von Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Brahms und Bartók.) Um es deutlich zu sagen: Hören als Rezeptionsform gleicher Dignität wie Lesen und Sehen hat hier und nirgends sonst seinen Ort gehabt. Dass sie nur den wenigsten wirklich in vollster Form möglich war, hat das, was man „absolute“ Musik nannte, immer schon mit falschem Respekt belastet und sie vielleicht zu jenen Distinktionsfunktionen pervertiert, die Pierre Bourdieu beschrieben hat. In der Saison 22/23 der Berliner Philharmoniker war übrigens das erste, sofort ausverkaufte Konzert jenes, in dem der Filmkomponist John Williams eigene Werke dirigierte. Man mag das als Ausnahme entschuldigen, und das Publikum war auch nicht dasselbe wie sonst. Aber es war auch im Betragen kein grundsätzlich anderes, und natürlich spekuliert die Rotation des immer gleichen symphonischen Repertoires auf den gleichen Effekt wie die sattsam bekannten Filmmelodien: Hören ist auf dieser Stufe Wiedererkennen. Während John Williams indes auf diesen Effekt spekuliert – schon aufgrund der leitmotivischen Verwendung im Film –, bedeutet er in einer Beethoven-Symphonie eine Verzerrung der komponierten Sache: Hier ist beim Wiedererkennen von Material immer dessen Funktion im Verlauf mitzubedenken, der emotionale Effekt des Erkennens soll begleitet werden von einer Erkenntnis.

Aber mag in der „absoluten Musik“ auch eine historisch einzigartige Höhe des Komponierens erreicht sein, so ist dennoch die symphonische und Kammermusik bei weitem nicht die einzige und das kontemplative Hören nicht der einzig gültige Rezeptionsmodus. Schauen wir in die Oper, so sieht die Sache schon nicht ganz so hoffnungslos aus. Sie ist zumindest von der Autonomie-Lüge befreit, indem sie sich mehr oder weniger eng mit einer Bühnenhandlung verbindet. Zwar dreht sich das Regie-Theater immer mehr um sich selbst, aber es ist abzusehen, dass die meist noch sakrosankten, von der Partitur vorgegebenen Ordnungen künftig aufgelöst werden, was einen gewaltigen Kreativitätsschub auslösen dürfte, der endlich wahrhaft neue Ansichten des Repertoires erlaubt – davor kann man natürlich auch Angst haben.

Vor allem ist der singende Mensch im Unterschied zum gedrillten Instrumentalisten noch immer eine unberechenbare Instanz von begrenzter Perfektibilität und unausrottbarer Individualität. Seine Ausstrahlung reicht hinein bis in jene Form, in der sich Rezeption und Produktion mischen, in den Chorgesang. Dass sich in Chören auch eine Form von pseudoexpertenhafter Borniertheit kultivieren kann, ist richtig. Allerdings entsteht hier eine Verbundenheit mit einer Tradition, die von einigen Chorleitern durchaus engagiert auch in die Gegenwart geführt werden kann. Es gibt Laien- und semiprofessionelle Chöre von erstaunlicher musikalischer Qualität, die erstaunlich zeitgenössische Programme singen und dabei natürlich unter „zeitgenössischer Musik“ etwas anderes begreifen als die Spezialensembles für neue Musik, die aber doch mit neueren Tendenzen – dem erklärten Ende weiterer Materialerweiterung, dem Arbeiten mit vorhandener Musik – erstaunlich eng zusammenhängen. Und dass solche Chöre durch die zwangsläufig längere Arbeit an solchen Projekten enger mit den Stücken in Verbindung treten als Profiensembles, die für eine Uraufführung anderthalb Proben ansetzen, versteht sich von selbst: Schon durch die investierte Zeit in die Erarbeitung eines neuen Werks erhält dieses Werk einen höheren „Wert“ als eine von zig Uraufführungen, die etwa die Musiker des Ensemble modern im Jahr spielen. „Wert“ wird hier nun vielleicht nicht mehr aus „autonomen“ Gesichtspunkten heraus zugeschrieben. Aber das betont nur, was Musik vor allem ist: eine soziale Angelegenheit.

Wie verhält sich nun Musikkritik dazu, die ja parallel zur Autonomie-Ideologie entstanden ist und immer die Aufgabe hatte, das Gehörte für den Bürger, der wenig davon verstand, aufzuschlüsseln? Dabei bemerkt man schnell, dass man oft genug für Leser schreibt, die sich gar nichts aufschlüsseln lassen wollen, sondern öde bemerken, man hätte offenbar ein anderes Konzert besucht als sie. Von Kritikerseite aus wäre zu fragen, warum jemand, der sich seines Urteils offenbar sicher ist, dann überhaupt eine Kritik liest? Kritik will nicht besserwissen, sondern die Kriterien und Perspektiven des Lesers erweitern. In diesem Sinne bezieht sie den Standpunkt einer Autorität, den man als „mikroaggressiv“ empfinden kann – aber wer so empfindet, will wirklich gar nichts mehr wissen, sondern nur noch seine Identität (vulgo: Unbildung) verteidigen, man befindet sich nicht mehr in einer „Kultur des Diskurses“, sondern in einer „Kultur des Dispositionen“ (Markus Metz/Georg Seeßlen: Apokalypse & Karneval, Berlin 2022, S. 8). Und es ist unverständlich, warum eine im Punktesystem und diskursfrei dargestellte Empfehlung weniger autoritär sein soll.