ARTICLE

Yuval Sharon’s Twilight: Gods (2020-21):

Site-Specific Reimaginations of Richard Wagner’s Götterdämmerung

*

Jingyi Zhang

Sound Stage Screen, Vol. 3, Issue 1 (Spring 2023), pp. 73–111, ISSN 2784-8949. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. © 2023 Jingyi Zhang. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54103/sss20750.

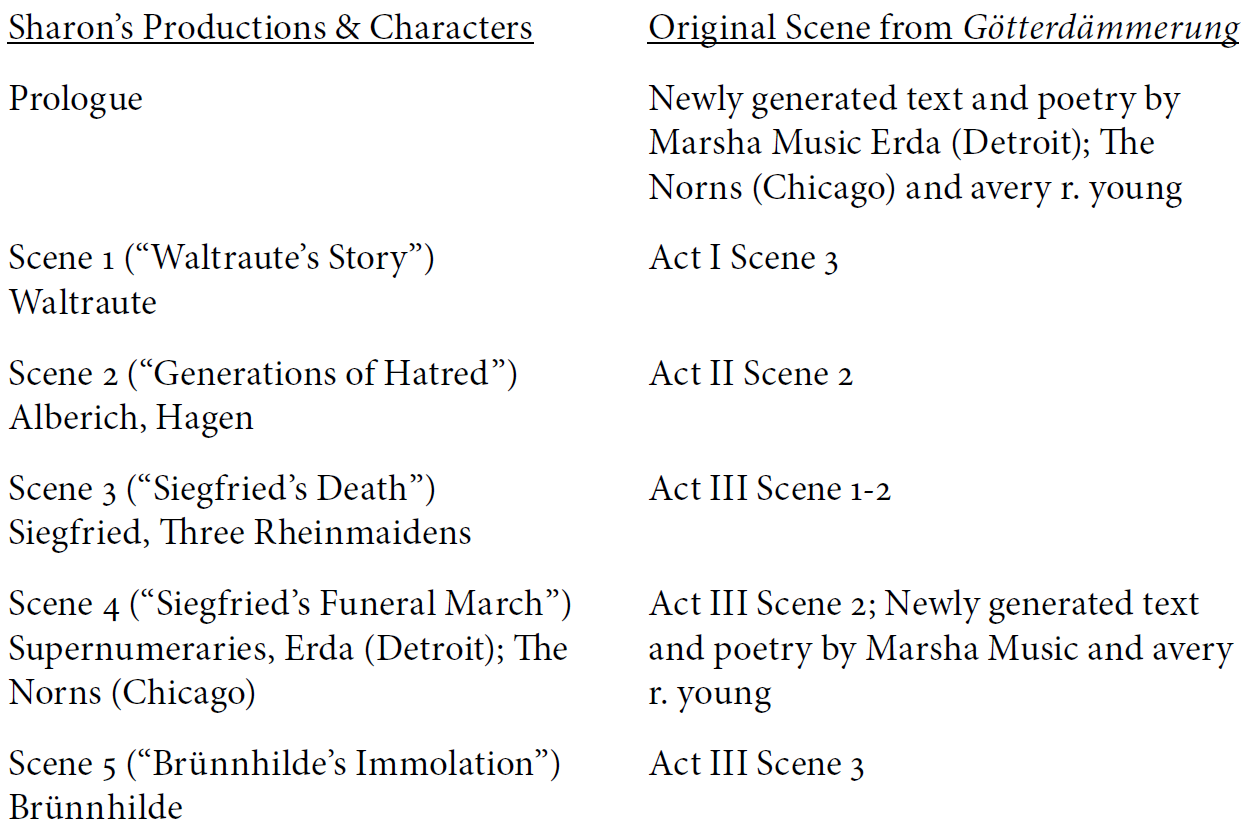

Twilight: Gods, conceived and directed by Yuval Sharon, was a drive-through opera that presented an hour-long reimagination of Richard Wagner’s Götterdämmerung. I use “was” to underscore its ontology: it existed for its first staging in the Detroit Opera House Parking Center in October 2020 and was subsequently performed in Chicago’s Millennium Lakeside Parking Garage from April to May of 2021 before drawing to a close. Both productions were co-commissioned by Michigan Opera Theatre (now called Detroit Opera) and Lyric Opera of Chicago. In this massively abbreviated reimagination, the adventurous director-producer Sharon adapted six scenes from the opera, the lyrics were translated into African-American Vernacular English (AAVE), and a drastically reduced orchestra performed different musical arrangements for every scene. Choosing a parking garage as a performance space was motivated by pandemic-related concerns but also shaped by creative thinking about operatic performance during lockdown. The event invited audiences to reflect on an experience utterly unlike canonical works as usually produced by large opera companies. My account is grounded in recordings made in-house that Sharon shared with me. [1]

As the new artistic director of Detroit Opera, Sharon was quick to introduce the radical artistic visions he has been cultivating with his experimental opera company, The Industry, into his very first project in Detroit and Chicago, signaling the ascendency of a creative dialogue occurring in today’s operatic ecosystem. [2] At The Industry, Sharon is known for taking opera off anything resembling a traditional proscenium stage and resituating it in alternative public spaces and unconventional sites: moving cars, a train station, and the LA State Historic Park. Not only did Twilight: Gods aptly meet pandemic-era restrictions by adapting to the necessary social distancing measures, but it was also “a very Yuval Sharon production” in the words of João Pedro Cachopo, with the pandemic serving as “an opportunity, or pretext” for Sharon’s bold endeavor. [3]

Sharon staged a deus-ex-machina solution in the parking complex (pun intended) by transforming it into a theater and choreographing car movements through the multiple levels, evoking what David J. Levin calls the “geographization” of circling up and down in Wagner’s Ring. [4] The performers’ voices and instrumental music were broadcast through FM channels for audiences to hear via their car radios (this ensured they stayed completely socially distanced). [5] Spectators watched each of the six selected scenes as they drove up each level of the garage, and were asked to tune in to a different radio frequency every time, an action that further marked the transit between scenes. In so doing, the creative team simultaneously captured the apocalyptic moment back in 2020 where we were all forced to be “atomiz[ed] … in a [technological] bubble” and enabled yet another instantiation of Wagner’s phantasmagoria of the invisible orchestra. [6]

Both productions boasted an acclaimed and racially diverse cast: Christine Goerke as Brünnhilde; Sean Panikkar, tenor of South Asian descent, as Siegfried; African-American bass Morris Robinson as Hagen; and celebrated mezzo-soprano Catherine Martin as Waltraute. Detroit Opera collaborated with poet Marsha Music, Detroit native and the daughter of pre-Motown record producer Joe Von Battle. Besides performing the role of Erda/Narrator, Music wrote and performed new poetry, which added references to what was, in 2020, a newly pandemic-stricken landscape of detritus culled from Wagner’s opera. The Lyric Opera of Chicago for their part collaborated with local interdisciplinary artist avery r. young who not only played The Norns/Narrator but also composed new texts centering issues of systemic racism in the present-day US.

Both performances and productions of Twilight: Gods in Detroit and Chicago demand an extended investigation into the technological and ideological dimensions of site-specific reimaginations. But first, it is critical to contextualize them within the broader genealogy of site-specific and drive-through operas, and in particular Sharon’s projects with The Industry. With these key set-ups in place, I call into question the notion of immersion as an essential part of the operatic experience, and put forth re-enchantment as an alternative phenomenological model, which captures the sense of play underlying site-specific operas. Building on Carolyn Abbate’s concept of “ludic distance,” I posit that re-enchantment is derived from our hyperawareness of the material dimensions of hybrid media and technologies fleshed out before us. An intriguing moment of white noise in the Epilogue, I illustrate, simultaneously generates visceral pleasure in audiences and provokes reflections on the technological nature of the performance itself. [7] Moving on then to explicitly ideological considerations, I pose questions about the progressive aspirations of the creative team through a close examination of Scene 4 (“Siegfried’s Funeral March”). Similarly troubling questions ensue from examining the ethics and politics of collaboration with the two Black poets who wielded significant creative agency in the opera.

The Drive-Through Opera: Experiencing the “Third Space”

Instead of approaching Twilight: Gods as driven by either the individual director’s vision to “decolonize” opera or the pandemic alone, one must examine the broader phenomenon of drive-through opera and situate Twilight: Gods alongside Sharon’s prior body of unconventional works. Only then can we better understand how site-specific opera engenders a novel mode of spectatorship evoking the concept of “third space,” defined by Edward Soja as “a space of extraordinary openness, a place of critical exchange,” which encompasses “a multiplicity of real-and-imagined places” that might be “incompatible [and] uncombinable.” [8]

Since the beginning of the pandemic, several opera companies, like the Deutsche Oper Berlin and Opera Santa Barbara, have been staging performances in garages; thus, Twilight: Gods was neither radical nor novel in this regard. [9] But those endeavors were largely understood as temporary accommodations to the constraints of the moment, which preserved the basic mode of spectatorship. [10] Sharon’s reimagination, in contrast, went beyond mere logistics. He not only undid staging conventions but wrote his own abbreviated English libretto. Furthermore, the creative team reorchestrated the work anew and collaborated with local artists Marsha Music and avery r. young in the Detroit and Chicago productions, respectively. Though the Götterdämmerung libretto was radically cut down, whenever Sharon did use a scene from the original, the text might have been slightly shortened but generally matched its Wagnerian source: a brief tasting menu drawn from a gargantuan original.

A brief walk-through of Sharon’s abbreviated narrative ensues: Erda/The Norns opened the Prologue, appearing on a filmed video played outside the parking garage as they boiled down the Ring’s backstory in AAVE within a few minutes. They continued their narration through the interscene audio feed, functioning like a soundtrack as audiences drove up to the next level. Scene 1, drastically shortened from the original, depicted Waltraute delivering a monologue on her disillusioned father, Wotan, who awaited the destruction of his empire. While Wagner portrays Waltraute begging her sister Brünnhilde to return the ring to the Rhinemaidens, Brünnhilde did not perform here since each singer could only appear once, and Christine Goerke, who played Brünnhilde, must sing in the final Immolation scene. Scene 2 was taken verbatim from the original, featuring Alberich persuading his son, Hagen, in his dreams to help him claim the ring by killing Siegfried. Scene 3 portrayed Hagen stabbing Siegfried to death, followed by the obsessive repetitions of Siegfried’s Death motif before dovetailing into Scene 4, the highlight of the opera. Marsha Music and avery r. young, who played Erda and The Norns respectively, engaged in a live narration that adapted Wagner’s Ring to the US context today. New musical content was also presented here: a Motown-style spectacular lightshow orchestrated and arranged by Ed Windels while accompanied by dancing stagehands. Scene 5 depicted Brünnhilde riding off into the funeral pyre in a Ford Mustang convertible (in the Detroit production), which she addressed—faithful to the original libretto—as “Grane, my horse.”

As discerned from my brief account, while all theaters, as architectural spaces and as artistic genres, involve “third space,” this particular performance event was much more complex and layered. Not only did we have the parking garage space, but there was also the imagined past Germanic landscape of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, the nineteenth-century past of Wagner, and traditional theater staging. A certain fantasy appeal came with the idea of performing an opera in a Detroit parking garage, given the city’s reputation as the “Motor City” of times long ago, though it remains debatable whether both productions managed to forge “deeper connections” with local communities as Sharon promised. [11]

On Re-Enchantment: Fleshing out Media

Situating both productions alongside other site-specific operas produced by The Industry illuminates broader trends in today’s experimental opera scene. [12] The drive-through nature of Twilight: Gods and the mediated listening experience combine aspects of Hopscotch (2015) and Invisible Cities (2013). Both operas were directed by Sharon, who then contributed his artistic vision to Twilight: Gods. [13] While audience members in Twilight: Gods listened through their car’s FM radio, audiences in Invisible Cities donned on wireless headphones as they roamed through Los Angeles’ historic Union Station. [14] Hopscotch, which came two years after Invisible Cities, shared more similarities with Twilight: Gods. Billed as a “Mobile Opera for 24 Cars,” it seated audiences in limousines as they were driven across LA to witness singers perform in each locale, at times singing in the same car as them. The orchestra was often heard through the car’s FM radio but sometimes instrumentalists performed inside the car. In both mobile operas, everyday non-artistic, “invisible” activities were reconfigured into new modes of performative engagements and technical play. [15]

These site-specific performances have led historians to propose new operatic phenomenologies, positing heightened immersion on the part of audiences. As there is no stage, no fixed viewpoint, and no proscenium arch to tell audiences how to orientate themselves, a more intense and attentive engagement is said to ensue as the producers and some scholars suggest. But I want to challenge this perspective, first by outlining scholarship that addresses certain phenomenological and sociological aspects of site-specific opera. Wagner’s own vision of immersive acoustics (manifested in the design of his Bayreuth Festspielhaus) is ridden in practice with paradoxes, which have been analyzed by Gundula Kreuzer. [16] Then, we come to a final question: does recognizing the futility of technological illusion generate disenchantment or “re-enchantment” in the genre of site-specific opera?

The promotional language of Twilight: Gods is saturated with references to seamlessness in the operatic experience. The performance event was described as a “part immersive installation,” which “connects Wagner’s mythological world with the here-and-now of our city and our time”—a formulation that seems to allow no gap (no dropped call, no missed connection) between the fictional world of the opera and the physical site of the performance. [17] For some critics, this is taken as a given and a plus for all site-specific opera: for instance, Megan Steigerwald Ille foregrounds the immersive and interactive aspects of site-specific opera in discussing The Industry’s 2015 mobile opera Hopscotch. She suggests that the marriage of the opera’s fictional world with the physical site of performance “validated [the] audience members’ feelings” that they are actively participating in the operatic diegesis. [18] Audience co-creation of an identifiable, shared meaning is seen as contributing to a heightened sense of immersion, which is enabled, as she sees it, by how Hopscotch prioritizes the visual over the aural in storytelling. By inviting audiences to “engage with space first, and sound second,” [19] site-specific opera positions sound as secondary to the visual spectacle, and this hypothesized prioritization is critical to an immersive force.

However, does immersion inevitably enable illusion (or vice versa)? Is sight indeed prioritized over sound? And how exactly does the alternative site construct new layers of “unsettling” possibilities, triggering perceptions and interpretations that are inspired by the non-theatrical environment?

We might start by reimagining “site,” seeing the site not as a simple geospatial given—man-made structures plus landscaping with specific GPS coordinates, lying in wait—but as a physical locus that itself, weirdly and unpredictably gains an event-character by going from place to phenomenon through a dynamic interface with media, technology, bodies, objects, and the human imagination. This reimagination of “site” makes room for a noisy media ecology that embraces emerging meanings and serendipitous, incongruous experiences not obviously immanent to the site itself, perhaps not even enabled or made easier by it, nor foreseen in the original creative plan. We enliven site-specific opera by paying attention to the unscripted—technological glitches and random accidents—which should all be reconceived as generative processes leading to a re-enchantment that is, specifically, not predicated on immersion.

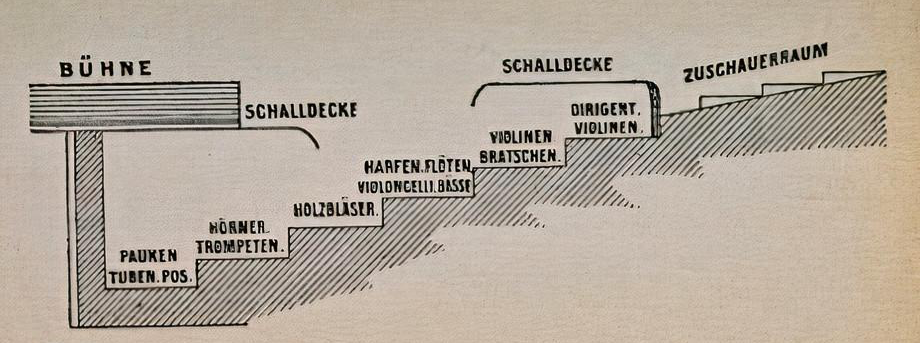

In order to untangle immersion, illusion, enchantment, and the accidental, we do need to make a brief detour, and consider the theater where the immersive experience of opera has conventionally been said to originate: Wagner’s Bayreuth. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus manifested Wagner’s vision of ideal acoustics that resulted in immersive listening, speaking to a genealogy of acoustic thought dominating nineteenth-century listening habits. Innovations famously included hiding the orchestra pit, so audiences could be completely absorbed by the stage action, and arranging the orchestra on descending steps, which shapes the sound in uncanny ways, generating an immersive acoustics. [20] Consider one of scores of cross-sections of the Bayreuth stage published since 1876: this one is from 1904 (see figure 1). These innovations are now legend: the orchestra pit was completely covered over such that audiences were unable to see the orchestra—the human labor of sound production—nor even the reading lights on the music stands of the musicians. In this way, the audiences’ attention was (or, so as the theory goes) fixated on the stage.

This theory has received support from scholars including Nina Eidsheim and Megan Steigerwald who affirm that Wagner’s Bayreuth contributes to an immersive listening experience. Eidsheim asserts that the psychoacoustics of a well-designed concert hall gives rise to the “feeling of being immersed in a sound.” Steigerwald argues that site-specific productions simultaneously participate in the genealogy of immersive listening associated with Wagner’s Bayreuth and enact notions of estrangement in performance. [21]

Fig. 1 – Cross-sectional view of the hidden orchestral pit in Wagner’s Festspielhaus. Wolfgang Golther, Bayreuth (Berlin: Schuster & Loeffler, 1904), 80.

But was the theory correct? Drawing on Gundula Kreuzer’s work, I expose an inherent paradox illuminating an underlying tension between theory and practice, which makes us re-consider the whole myth of immersive listening and its application to site-specific opera. [22] While Wagner resorted to strategic architectural maneuvers that aimed at an illusory, immersive experience for audiences, Kreuzer has dismantled his edifice. In Curtain, Gong, Steam, she exposes the ultimate failure of Wagner’s illusionist agenda. Exploring contemporary theatrical illusionist technologies like steam (intended to veil both the artificiality of stage representation and its own nature as an industrial product), she argues that the multisensorial nature of Wagnerian technologies could never overcome its own material realities. [23] The hissing sounds created by the steam engine that sprouted out the mists and vapors, as well as the oily, metallic odor given off, shatter the illusionist agenda that Wagner painstakingly strove for: the mechanicality of technology is always evident. [24]

Kreuzer posits a failure of the Wagnerian immersive agenda and describes a layered tension between the theory and practice of his technologies of immersion. As she indicates, on the one hand, he pushed for the return to nature in his operas, and on the other hand, he inadvertently depended on the very technologies (steam engines, stage machines, sophisticated props, architectural affordances) to summon “nature” to the stage. Furthermore, while he relished advanced operatic technologies, he had to conceal the technological mechanism so that the “phantasmagoria” would not lose its ability to delude. [25] Kreuzer makes us realize that the sense of smell—but more radically, also the sense of hearing—can be disenchanting senses “exposing technology” at work, always bringing the subject back to the consciousness of his or her own body in space, in time, and in history.

The conundrum of Bayreuth is relevant to site-specific opera, but not in the way we might first assume. Kreuzer makes an association between technological “reveals” and disenchantment. But in Twilight: Gods, technological “reveals” can engender, instead of flat-out disappointment, a sense of awe. Yes, the pursuit of technological illusion is futile—due to technology’s very inability to overcome itself—but in Sharon’s version, a technological “reveal” makes space for re-enchantment.

In site-specific stagings like Twilight: Gods, re-enchantment is not about being immersed in and transfixed by a fictional stage world, but about the cultivation of an alternative model of spectatorship—what Carolyn Abbate calls “ludic distance”—which is characterized by a simultaneous absorption in and detachment from the singular experienced performance. [26] Enchantment is derived not despite but because of our hyperawareness of the material underpinnings of the hybrid media and technologies laid bare before us, [27] thus gesturing to the ontological notion that we experience awe precisely because we are reassured by constant affirmations of the real-ness of the world.

To begin with, the very nature of the drive-through operatic experience abounds in contradictions. Immersive? Far from it. Viewing the performance from inside a car insulates audiences from the live action itself. Proximity between audiences and performers, and the enveloping lighting design—these are pro-immersive elements. But being confined within one’s car and constrained by technologically mediated listening—live sound outside your window, plus simultaneous radio broadcast, plus the growl of the internal combustion engines surrounding you—push the opposite way, leading to a barricaded, distant experience. The listening experience even provokes acousmatic anxiety—where is the mouth that is singing? That one there, or over there? Is it live or is it lip-synched?

The experience of an audiovisual gap attests to the broader phenomenon of operas that involve mediated listening such as Invisible Cities. [28] But rather than engender “distance” or “disconnect[ion],” as Eidsheim claims, this phenomenological experience takes on the form of distracted pleasure, which holds true even before the start of the performance event. [29] In what follows, I draw on the 2020 video recording to illustrate key insights. I will be using “was” to describe the event, and while my verb tenses necessarily shift during my analysis—and I refer to an opera (a “work”) with an ostensible permanence—the ephemeral reality of the event should not be forgotten.

Multiple objects of interest competed for audiences’ attention the moment they trailed into the parking garage. An apocalyptic mood set in right away, contributed by static blocks of indecipherable pitches existing purely as timbre. Attention was soon after diverted to other masked audiences entering the garage and security staffs who were maintaining site safety. This apocalyptic mood extended beyond the diegetic world to the real world outside, which could further be thought of as belonging to the operatic experience itself. [30] This perspective is echoed by musicologist Nicholas Stevens who drove all the way to Detroit to watch the opera. Making sure to avoid contact with anyone along the way, he characterized his road trip experience as deeply isolating and ominous. [31] This gestures to the idea that an audience experience that extends beyond traditional performance spaces makes one particularly prone to a form of perceptual awakening. One’s sensory horizon is expanded by feeling the space and continually being enchanted by the idiosyncrasies of the new site. [32] Therefore, getting past opera’s illusionist agenda and refocusing on the interactions among various materials expands the notion that audiences, performers, stagehands, and the site itself are collaborative, co-constitutive media of this new operatic fabric.

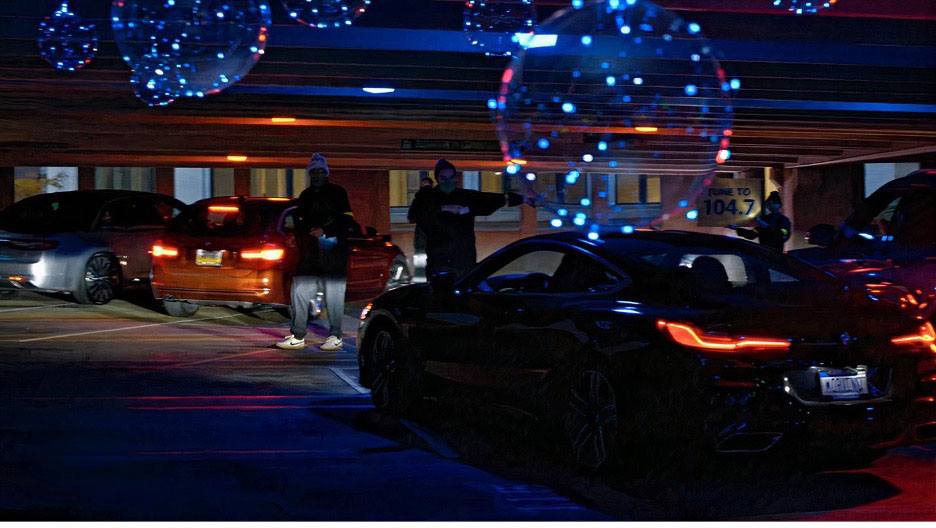

Once the cars entered the garage, audiences found themselves enveloped by the purplish and cyanish hues of the interior (see figure 2), which subjected them on the one hand to the hypnotic effect of the lighting, but, on the other, heightened their cognizance of its mechanism as the production of technological labor was laid in plain sight before them. This included the technologists’ sophisticated maneuvering of professional gadgets and the physical operations of stagehands. Throughout the performance, black-clad stagehands were conspicuously visible, responsible for moving scenery while in plain sight and facilitating the opera, evoking the role of kuroko (stagehands) in Japanese Kabuki theater who are similarly visible in black costumes. While they do not directly participate in the stage action, these figures recur throughout and remain quite visible. [33] As drivers ascended to the next level of the garage, more stagehands and technologists appeared, making no attempt to conceal the operations of changing scenery and ensuring safety.

Fig. 2 – Panning shot of cars entering the parking complex right before Scene 1 (“Waltraute’s Story”). We heard a static chord played by a synthesized keyboard, and saw visible stagehands facilitating the event.

Throughout the evening, the stagehands gradually took on more active roles, culminating in Scene 4 (“Siegfried’s Funeral March”) where they became the star performers in a celebratory light show seen through a thick mist (see figure 3). The march began more or less as in Wagner’s original, albeit with reduced orchestration. But then, there’s a sudden shift, a fundamental recomposition amounting to an entirely new piece: a quasi-1960s Motown episode, generating a strong groove through the rich blend of wind and percussion instruments articulating rapid passing notes, chromaticism, and climactic punctuations on important beats. Slowly weaving through the cars, the stagehands shone their flashlights on graffiti on the walls, illuminating the names of dead gods. They broke into a synchronized dance, with their flashlights as props: orange, white, and purple cones of light flashed through the space.

Fig. 3 – Lightshow in Scene 4 (“Siegfried’s Funeral March”) where car headlights, candles, and flashlights emitting various hues constituted the overall visual fabric of the opera. © Mitty Carter/Michigan Opera Theatre.

The stagehands morphed into supernumeraries, into a kind of Detroit Techno ballet troupe. They inhabited the story world and were no longer merely arranging that world’s props and scenery. Audiences, likewise, were no longer passive viewers, but “co-creators” within the operatic setting as they “perform[ed] ‘double-duty’”—as both audiences and facilitators of the performance. [34] Phenomenologically speaking, this scene seemed tailor-made to illustrate Kreuzer’s point—audiences were forced to confront the technology of the performance. The well-lit garage generated a plethora of opportunities for serendipitous performer-audience co-creation of spectacle, which ran alongside the operatic performance. In the process, the mode of reception shifted to the third-person, which allowed one to oversee the event from a distanced perspective. But beyond that, the distracted pleasure engendered by the oscillating interplay between the fictional world and the technological labor of the performance resonates with what Abbate calls “ludic distance,” which enables audiences

to be aware of and susceptible to representations of a magical world, and to sensual music, in a state of mixed absorption and distraction that is not necessarily inimical to (or disdainful of) that world or that music. And it is not that we are “absorbed” in the work and its fictions and “distracted” by the singers or the performance. It is also possible, and no small pleasure, to be “absorbed” by the performers or the materiality of the performance, becoming “distracted” by the very process of getting caught up in the fiction. … It’s in effect a state of delight in technology, in the sense that how things are made, and the means and media and errors through which they come to be, are essentially technological amusements. [35]

This phenomenological model effectively captures the sense of play underlying the performance marked by its media plenitude, leading to the oversaturation of the senses and a greater freedom in choosing what to focus on. Unlike in a typical operatic setting, which strives for immersion by concealing the source of light in the illusion, pulling spectators away from the here-and-now in the dark to the brightly lit onstage spectacle, in Twilight: Gods, the spectacular lightshow put up by the stagehands, cars, and candles fleshed out before our eyes what immersion is all about: a visual illusion invoked and sustained by illumination. When the operating mechanisms lie naked in front of audiences, revealing their workings, part of the magic is inadvertently lost. But it is a habit of thought to equate the technological “reveal” with the removal of fantasy or enchantment. Wonder is not diminished; instead, it is elevated in such moments, which in turn generate more questions. Admiration is provoked by simply being aware that something ordinary can become extraordinary. And that results in a heightened sense of wonder.

Beyond Wonder: Ineffable White Noise

Fig. 4 – Final scene where Christine Goerke performs Brünnhilde’s Immolation scene on the rooftop, among the crushed shells of burnt-out cars. © Mitty Carter/Michigan Opera Theatre.

Another way of considering this phenomenological model is to say we look at the medium instead of through it. This same effect became overwhelming in the Epilogue, when site determines sounds as much as sounds create or evoke site. The ending had Christine Goerke perform Brünnhilde’s Immolation scene on the rooftop level, among the shells of burnt-out car wrecks, departing afterwards in a custom-built white Ford Mustang convertible (see figure 4). Then, Erda’s voice entered, accompanied by the continuous hissing of white noise over the FM radio as she concluded the opera as follows:

And here today are hallowed halls

That must come down, ‘tis time to fall

Constructed of a filthy sod

of hate and greed, those lesser gods

Tis time to see them all be gone

Their twilights given way to dawn

And generations bound and trussed

Be loosed and freed and lifted thus

The twilight of old gods is soon

The time of Götterdämmerung

[36]

And it’s exactly here that we heard technology’s unruly operations loud and clear; they were embodied in white noise broadcasted with and through the musical performance, effectively undermining the operatic plenitude and estranging audiences from Wagner’s monumentality at the end of the Ring. [37] While audiences were expecting a spectacular finale, the wrecked cars, smoke, and white noise evoked a dystopian Motor City/Valhalla. This is an example of what Melle Kromhout calls the “noise resonance of sound media”—fluctuating shades of white noise now becoming the main musical event, eventually overtaking the performance itself. [38]

What was both unsettling and intriguing here was not the music, but the recorded white noise that spilled into the diegetic world of opera, pushing one to ponder what exactly this was. Several audiences singled out this anxiety-inducing moment, reminded of the uncanny buzzes they heard in garages when spatial interference disrupted their radio signal. This might be true here. Audiences were driving up to the top level and tuning in to a new channel, which might have generated the static. Or it could have been the scratchy sound of a stylus running through the groove of a vinyl record. If so, the noise would intentionally render a sense of pastness and its associated intimacies. This striking evocation of sonic references to the media of Motown stimulated audiences to look back on and be reminded of Detroit’s Motown history.

On a more fundamental level, audiences were listening to the acoustic traces of technological mediation as they journeyed through time and space, crashing into a musical performance that asked them to hear, listen, reflect, and remember the technological nature of the audible white noise—a sonic counterpart to Kreuzer’s steam—betraying its own materiality by exposing the channels through which audiences consumed the operatic performance. [39] In the process, audiences were made acutely aware not only that they were receptors of operatic stimuli but also that they derived visceral pleasure from this distracting interplay of acoustic materialities where performance constituted only one aspect of the experience. This awareness effectively undermines the claims of immersion often associated with site-specific performances.

In understanding the visceral pleasure associated with such “noisy” moments, one need look no further than stagings in traditional theaters, particularly moments when noises happen both on and off stage, the former belonging to the operatic diegesis while the latter accidentally and distractingly reveals the inner clockwork. Despite the presence of extraneous noises, a certain moving appeal is derived. The sudden intensification of auditory attention in response demonstrates a sharp transition from what James Wierzbicki calls “wrapped” to “rapt” listening, the former referring to an everyday mode of listening one “likely take[s] for granted” while the latter has “nothing at all to do with the content or quality of the music, or the sonic phenomenon, at hand” but “only with the intensity with which the listener relates, psychologically, to the sonic stimulation.” [40] White noise and accidentally distracting moments in operas jolt audiences into a “rapt” state, which enables them to embrace sound’s multiple potentialities.

White noise gestures to an “unsettling” site of meaning-making: it simultaneously represents acoustic surplus and resistance to interpretation. [41] On the one hand, this drastic moment forces a point-blank confrontation with what’s there—the graininess, distortions, and randomness of sounds, having no time for meaning. On the other hand, it encourages one to listen elsewhere—searching for meaning lying “beyond the frame or behind the technology”—as one tries imposing one’s own spatial subjectivities and fantasies onto the site. [42] Ephemeral associations transport the audience to a kind of “third space” that co-exists with the performance unfolding in the here-and-now.

Staging opera outside of the familiar grandeur of the theater in the anxiety-inducing space of a garage cultivated a heightened receptivity to the spatial experience of a specific time and place, opening up new worlds of meaning. The dingy top level of the parking garage, accompanied by the hum of dystopian white noise and crackle of burning cars, created the effect of immediacy, calling forth the atmosphere of apocalypse so characteristic of 2020 that was otherwise inaccessible in one’s everyday life. Through exposing the material heterogeneity involved, white noise brought together both real and imaginary spaces that coexisted and extended beyond the borders of sound itself.

Furthermore, white noise unveiled the disparity between what one saw (Christine Goerke leaving in a Mustang and instrumentalists playing away) and what one heard (buzzing white noise), creating an uncanny collision of senses. In a single acoustic moment, listeners temporarily inhabited two sites at once: the real, physical site that occupied their vision, and a phantasmic one triggered by audible information, each jostling for attention. [43] This sensory disjunction makes one question the literalness of site in site-specific performance: how much of one’s experience is rooted in site, about site, and beyond site? It might be freeing to pursue a notion of site that transcends the physicality—and one’s assumptions—of place. This is a critical point to bear in mind for it goes against the immersive argument. The parking garage could even be reconceived as an instrument capable of producing its own idiosyncratic sounds and sound effects apart from the score, which directly constitutes the phenomenal reality of the performance. But far from being epiphenomenal to the performance event, white noise took on immense efficacy here by making one hyperaware of the material basis and agency of the medium of the very music one heard.

While Twilight: Gods as a performance event engenders re-enchantment in audiences, both productions of the opera, which involved the performance of a collaborative effort, raise some thorny questions concerning racial politics and representation, thus demanding a more nuanced analysis. Present-day scholarship has tended to uncritically conflate the progressive intents of a performance with its overall effect or deliver a full-on neoliberal critique, which is then used as the chief basis for evaluating the opera’s merits. However, I believe that it is possible to deliver thoughtful critiques and simultaneously recognize the aesthetic merits of the performance and production. A just evaluation of an artwork’s overall significance is a balancing act that inevitably involves confronting difficult contradictions like this one.

Sincere efforts were made to create space for artistic collaborations with Black singers and writers, as observed in the predominantly Black casting for Alberich (Donnie Ray Albert), Hagen (Morris Robinson), and in the Detroit production, two of the Rhinemaidens (Olivia Johnson, Kaswanna Kanyinda). [44] Detroit poet Marsha Music and Chicagoan interdisciplinary artist avery r. young wielded creative agency in both productions as they not only composed new poetry, but also recited them as the narrator and Erda/The Norns during the performance. [45] Techno music broadcasted in the interscene audio feed and the Motown funeral scene are intended to invoke a collective cultural memory among local audiences who grew up with these familiar sounds. There is, however, a caveat that must be stated at once. No matter how well-intentioned the “hope” for inclusivity and the thought and labor that went into that goal, it is an open question whether, in the end, the productions succeeded in this regard—whether they truly fulfilled the ethical, redemptive terms they set for themselves.

First, it is key to contextualize Twilight: Gods within the broader discourse of opera’s problematic relationship with race, as observed in the “lack of [B]lack authorial voices and failure to represent [B]lack subjectivity,” as Ryan Ebright posits. [46] According to Naomi André, Black voices in opera have always been a rich but historically marginalized entity existing alongside the dominant “all-white and segregated opera scene” in the US up to the 1950s. This “shadow culture” is reflected in the scarcity of operas that fully center the Black experience. [47]

In this regard, though Twilight: Gods is not a fully-fledged Black opera but a reimagination of Wagner’s opera, the collaboration with Black artists (Marsha Music, avery r. young) who wielded actual creative agency in both productions might, at first blush, seem like a socially progressive act. This might even be interpreted as an attempt to wrestle with Wagner’s problematic legacy and opera’s racist history at large. [48] While the collaboration with Black artists, musical crossover efforts, and inclusive casting practice speak to the creative team’s progressive aims, one must be mindful of superficial displays of equality and not simply embrace the sharing of space—optically and musically speaking—as an automatic signifier of “progressiveness.” It is therefore critical to interrogate how the sound of Motown was materialized in Scene 4 (“Siegfried’s Funeral March”), who were presenting and representing it, and what it did to Wagner’s original leitmotif and the opera overall. Doing so demonstrates how whiteness structured elements in the productions while going unseen. Scrutinizing the politics of collaboration with Black artists through an ethics of listening will illuminate how racial politics underpinned the display culture of both productions. Here, engaging with Matthew Morrison’s Blacksound is crucial. [49]

Let’s first focus on how Motown was presented before analyzing what it did to Wagner’s original motives. The instantaneous shift from the leitmotif of Siegfried’s death to the spectacular Motown lightshow, which eventually became the triumphant highlight of the opera, speaks to the performance of Blacksound. While Scene 4 reflects the creative team’s desire to tap into legendary 1960s Black music, when Motown is being packaged by an all-white creative team as aesthetically accessible to an elite audience, the political stakes demand further investigation. Reducing Detroit musicality to audible stereotypes of Motown deprived a more meaningful engagement with Black musical traditions. Moreover, the episode did not cohere well within the overall framework for it had no bearing on the characters or drama beyond the display of Black musical tradition, thus striking one as simplistic. As observed in my transcribed score (see figure 5), the music started out with Wagner’s motif verbatim followed by a series of repetitions with slight modification. Then, suddenly, it switched to a Motown episode that was completely distinct from Wagner’s leitmotif, showing no attempt to transform or destabilize the original music within its frame. Instead, what we heard was the convenient merger between Wagner and Motown, each musical element kept separate from each other.

Fig. 5 – My transcription of Scene 3 (“Siegfried’s Death”) to Scene 4 (“Siegfried’s Funeral March”). Note how the transition begins with Wagner’s motif, then evolves into something else completely.

This mode of musical collaboration where Black popular music merely “serve[d] as a resource that add[ed] to art music” is premised on “fitting” Black music into the dominant Western paradigm. [50] The unwieldy integration into the largely undisturbed Western operatic framework simply celebrated a juxtaposition of discontinuous musical styles, [51] hence perpetuating what Robinson calls “sovereign values” and resistance against “aesthetic assimilation.” [52] The lack of creative friction between Wagner’s opera and Black musical culture in Sharon’s production rejects the possibility of a mutually transformative encounter, thus undermining the progressive agenda the creative team initially set out to achieve.

One must also consider who wrote this music and for whom? Instead of collaborating with a Detroit-based composer as one would expect, the creative team worked with Lewis Pesacov from Los Angeles, who also performed the music in this scene. The use of recorded audio reflected a further instance of erasing Black bodies in performance. Choosing to engage with Motown music but not collaborating with Black composers and musicians bespeaks the exploitative act of cultural ventriloquism—literally and metaphorically speaking—which does not do justice to the Detroit production and its progressive intent.

Besides examining the framing and materialization of Motown, one must also consider the ideology and ethical implications of employing pop music, a musical practice that includes Black commercial enterprises. Simon Frith draws attention to the easy accessibility of pop music, defining it as a “slippery concept” as it is “so familiar, so easily used.” [53] This is manifested in practices of “voracious borrowing and adaptation,” which generate ‘“pop’ versions” of all musical genres. [54] In short, “anything can also be popped.” [55] This usefulness of pop music, which defines its core sensibility, paradoxically somewhat makes it a non-entity as Frith describes:

Here pop becomes not an inclusive category but a residual one: it is what’s left when all the other forms of popular music are stripped away … From this perspective pop is defined as much by what it isn’t as by what it is. [56]

This “residual” feature of pop makes it prone to commodification today. Frequently viewed as “music accessible to a general public” and “designed to appeal to everyone,” pop can be perceived as a marker of “authenticity” by the audiences of Twilight: Gods. [57] The creative team might have thought that “updating” the opera’s soundworld with local traditions by deploying Motown could be a novel way to “struck an emotional chord with the public,” thus demonstrating its racially progressive stance. [58]

However, I would argue that the use of Motown music is far from progressive; in fact, their venture is motivated by its intrinsic use value. True enough, Motown is already a commodified musical practice that is use-ful. But to freely “draw and quote and sample” from an originally Black commercial enterprise as if it were a “social storehouse?” [59] The creative team’s appropriation of select Motown signifiers reflects an urge to own, use, and exploit Black music. In summoning imagined aspects of Black aesthetics, they were attempting to muster Detroit/Blacksound for the entertainment and edification of an elite, mostly white audience in Detroit and Chicago. [60] More importantly, the spectacular scene speaks to a certain dangerous “conflation of affect with efficacy” in the words of Dylan Robinson, where audiences felt that they had directly participated in social activism by experiencing the contagious performance. [61] This perspective resonates with Abbate, who posits that “physically experienced musical sound can create, in the listener, a somatic illusion that he or she has already acted and resisted, producing phantom engagement and unearned virtue.” [62] Likewise, in Twilight: Gods, feeling uplifted by the spectacular Motown performance is not equivalent to participating in any sort of antiracist act or committing to social justice. Worse, conflating affective feeling with doing can foreclose real change.

The Ethics and Politics of Collaboration with Local Artists: avery r. young and Marsha Music

Sharon’s restaging of Twilight: Gods in Chicago, six months after the Detroit production, brought about transformative changes to the new production, which generated a different reception and thus underscored an important principle in site-specific staging: it is not just the site that changes operatic content, but also the passage of time. This renewed emphasis on the ephemerality and contingency of performance therefore makes the timeline of an opera as important as the cities it circulates in. The lens of time demonstrates how the move from Detroit to Chicago resulted in evolving conceptions and new collaborations. Temporal breaks between performances are fertile zones of creativity providing the much-needed contemplative space for creative teams to implement new changes as necessary, after having taken into account reviews from the public and pondered over potential collaborative endeavors with local artists. Surprising results often ensue from this improvisatory approach to opera-making, as is evident in the evolution of Twilight: Gods.

As the production traveled to Chicago, Marsha Music no longer appeared. Instead, Chicago-based artist avery r. young stepped in to play The Norns/narrator. He sang, chanted, and recited a sizable amount of new text he wrote, which significantly reduced the proportion of Wagner’s original libretto that had been used in Music’s composed verses. The airtime difference was stark: Music’s opening pre-recorded narration of the Ring’s backstory merely took up four minutes while young’s spanned ten, a significant expansion considering that the production was only an hour long. Their presentation of contemporary events also varied greatly: Music merely alluded to the troubled times we were living in, while young made explicit references to racial injustice. As Amy Stebbins posits, contemporary libretti remain “an under-theorized object of study.” [63] Following her lead, I separately examine the libretti of Music and young, particularly the ways in which they were performed, to exemplify how the meaning of a production is contingent on the vagaries of its reception.

Marsha Music, who wrote narrative verses for the Detroit production, attempted to situate Wagner’s narrative in contemporary terms. She composed poetry that described the dark times of 2020:

And we can see today so much disarray and strife

Killing and conflict as a way of life

And the darkness and plague that’s upon our days

and the violence that rules and the chaos that reigns

There are warring souls and so much arrogance

Conflict and killing and great pestilence

To pandemic and plague, the world has succumbed

The end of days - it now has come

Jealousy, envy and skies fire red

And discarding and lying and defiling the bed

And courting then ghosting and boldfaced lies

And bragging and boasting, and making hearts cry

These innovations—featuring a Black female performer, surrounding assorted detritus from an antique Wagnerian opera with new poetic language and contemporary allusions, grounding Twilight: Gods generally in the context of both an ongoing pandemic and racial reckonings that were coeval with it—in sheer heterotopical accretion did not make the Detroit production progressive or antiracist. As André, Karen Bryan, and Eric Saylor caution, foregrounding Black artists on the operatic stage can still “lead to new and equally limiting obstacles” as it is not always easily discernible that there is a “division between minstrelsy and opera performances by [B]lack artists.” [64] I would argue that this conundrum is exemplified by the Detroit production, and facing up to it means being attentive to how Music self-fashioned herself, which raises complicated questions about assumptions drawn between an artist’s racial identity and authenticity in representing Blackness or the Black experience.

In character as Erda, Marsha Music opened the show by delivering the Ring’s backstory in AAVE, boiling down the first three operas into four minutes. Here are her first lines:

I am Erda, mother of earth, an oracle – a queen – for what it’s worth. I know past and future ’cause I’m clairvoyant. I’m primordial, mystical – and a little flamboyant. … I’m a real live goddess, a stone matriarch […] Now Wotan has a wife – no, he’s not all mine. I’ve been his side goddess for a very long time.

She continues riffing on the Ring plot throughout the show via interscene audio feeds.

Here we reach some extraordinarily complex questions, uneasy ones, maybe some unanswerable ones. Music’s participation, it seems clear, reflected the creative team’s hopes and desires for resonating with local Black audiences, a wish that opera, morphed and re-sited, might embrace a diversity of listeners. And yet, her interludes could be seen as belonging to the same category as the marked performance in the Motown Funeral March: firmly, loudly set apart from conventional operatic sounds, antique libretto language, or Wagnerian instrumentation or rhythm, just as the parking structure site for Twilight: Gods screams to audiences that they are not where opera usually happens. Is Music’s performance and poetry not also serving as an unassimilated “resource?” Or, in fact, does her involvement in the production, and the creative control she has over her narration make her portrayal, grounded as it is in her voice, presence, and agency, authentic and thus beyond reproach? How do we re-analyze Twilight: Gods in light of Wayne Brown’s integral role as one of the only Black presidents and CEOs of a US opera company?

Complex entanglements of race, gender, and sexuality come into play here. The Erda of myth, the white Nordic goddess, is radically challenged in Music’s performance. Old-fashioned expectations about Erda’s appearance—expectations we assume were carried into the garage by the largely white audiences that populated the performances in Detroit—are swatted away when Erda is represented as a commanding Black woman. And Music’s version of Erda, with her ironic wisdom and physical gravitas, seems to bypass yet another racialized expectation: what Kira Thurman—in referring to Grace Bumbry—calls “modern German notions of the primeval otherness of [B]lack female sexuality.” [65] And yet again, has Music indeed escaped stereotyping? Marsha Music wrote the words “side Goddess” and “real, live Goddess”—but was it a wind that blew during production, a particular costume choice, or a directorial fiat, that pushed things back over the border, to a racialized, exoticized Erda/Music?

Yet, there are facts on the ground: we know from documents connected to the Detroit production that Marsha Music actually had full creative control over all aspects of her performance. Besides writing her own poetry, she made her own costume and chose her own style of presentation. [66] Moreover, Wayne Brown, also a Black Detroiter like Music, was heavily involved in shepherding the production from its initial conception to the final performance, so he was clearly aware of her artistic decisions and the conversations occurring among the creative team. [67] As Music revealed in a forum post, wrestling with what “sound” she should go for was the key subject of the many conversations she had with Sharon prior to the performance. [68] Sharon’s insistence on Music narrating in her “Detroit voice” resonates with Music’s own aim “to sound ‘Detroit’—but not sitcom jivey.” Thus, she acknowledged “put[ting] some gumption (as [her] mother would say), into the narration,” which might have accounted for the eventual presentation. [69]

With this in mind, we then ask, could it be possible that our perception of Music’s role and expressive choices speaks less about her than about our stereotypes of Black femininity from a white gaze? [70] Put another way, perceiving Music’s performance as exotic and hypersexual might perhaps be attributed to our own assumptions about what opera performers should sound like (conditioned by our sustained exposure to established conventions of operatic timbre), which leads us to view any deviations unfavorably. But this view does not preclude the possibility that Music might also be resorting to a kind of self-conscious typecasting, which Eidsheim defines as the notion of having her “personal appearance and demeanor lend [herself] to a particular kind of role.” [71] In discussing her own performance, Music said she aimed to present “a sort of timeless tableaux” from her “earth-mother rocking-chair … next to an old lamp and a victrola.” [72] This revealing remark and Music’s description of herself as a “primordial Detroiter” affirms the possibility that she was self-fashioning to fit a certain stereotypical role. [73]

The Chicago production, which was received more successfully, exemplifies how six months’ lag has contributed significantly to the project’s evolution. young’s libretto wove together many localized allusions and narrative modalities resonating strongly with local audiences, further attesting to the creative possibilities engendered by artistic collaborations in site-specific productions. He animated his libretto with rich dramaturgical possibilities, invoking what Stebbins calls its “transmedial character,” [74] which builds “experiences across and between the borders where multiple media platforms coalesce.” [75] Joining forces with technology, young transformed his libretto into transcendent lyrics by “expand[ing] and enrich[ing] the canonical storyworld with new, culturally/socially relevant meanings.” [76]

young’s unmistakable foregrounding of the US history of racial violence is evident right from the Prologue. He alluded to lynching and captivity in repeated references to “rope” while literally holding on to a thick rope in both hands as he prophesied the destiny of the world:

We are the Norns

And our hands hold rope

We are the Norns

And our hands hold the rope of destiny

On this Stony Island,

We with rope tell you a story

Of how a Princess of Valhalla

Burnt all of the gods down.

What grounded his allusion in time and place is his translation of Brünnhilde’s rock from Wagner’s libretto to “Stony Island,” which refers to Stony Island Avenue, the main road running through Chicago’s predominantly Black South Side. These vivid spatiotemporal indicators echo Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the chronotope, which refers to “the intrinsic connectedness of temporal and spatial relationships that are artistically expressed.” [77] This sense of “connectedness” likely resonated with audiences who were experiencing Twilight: Gods in 2020–2021 America, a land overflowing with racism and xenophobia. By introducing the rope as a chronotope in the Prologue, young made it a literal and thematic concept, which accrued greater symbolic charge as it was intermixed with other objects later in his narration.

As young progressed, his allusions gained in speed and intensity, accompanied by the scratched visual surface filmed in black-and-white video with superimposed verses presented in all caps as shown below:

Her prayed

Siegfried knows a river

LIKE HIM KNOW ROPE

LIKE HIM KNOW TREE

Like him know how much dead

Make a bough break

LIKE HIM KNOW CAROL

LIKE HIM KNOW KAREN

LIKE HIM KNOW WHISTLES

LIKE HIM KNOW SKITTLES

LIKE HIM KNOW HANDS BEHIND HIM BACK

LIKE HIM KNOW CUFFS ROUND HIM WRISTS

Like him know how much skin

Concrete can chew

Like him know the weight of the patella bone

On him cervical vertebra

Whoa, I swear on the bodies at the fore of the Tallahatchie

Siegfried ain’t no stranger to a river

SIEGFRIED KNOWS RIVERS

And SIEGFRIED KNOWS RINGS

SIEGFRIED KNOWS RIVERS and RINGS

Like him know no

NO COLOREDS

NO JUSTICE

NO BAIL

No body but him body

Stuck in them illustrious image of him

MAGIC RIVER-RINGS

young used Siegfried’s death to draw connections to actual incidents of anti-Black violence, most notably the murders of George Floyd (1973–2020) and Emmett Till (1941–1955). The aesthetic immediacy of monochrome film simultaneously evoked the dark history of the Jim Crow era and reflexively alluded to the constructedness of race itself by blurring the boundary between Black and white.

Objects in Wagner’s mythic Ring transformed themselves into a patchwork of racist allusions through young’s dynamic delivery. The rope chronotope introduced in the Prologue started establishing polysemy relationships with related objects like the tree, bough, and river. The mixture of multiple temporal reference points further reflects an attempt to interrogate our present-day happenings through Wagner’s opera. Disturbing vignettes of contemporary racist incidents abound in young’s narration, including Derek Chauvin’s killing of George Floyd near Chicago Avenue in Minneapolis (“Like him know the weight of the patella bone/On him cervical vertebra”), and the death of fourteen-year-old Black Chicagoan Emmett Till whose body was found in the Tallahatchie River in 1955 after violating Jim Crow law (“Whoa, I swear on the bodies at the fore of the Tallahatchie/Siegfried ain’t no stranger to a river”). A passing reference to Martin Luther King’s Chicago residence was also made in young’s eulogy (“As for Hagen/Him bare-chested in a wave cap on a couch/In a 3rd floor apartment/Off the corner of 16th and Hamlin”) for this was where King led the civil rights movement in the mid-1960s, which remains today the most ambitious civil rights campaign in US history. Taking an anecdotal turn in his eulogy to Siegfried, young recounted a tragic memory of his friend Twan who was killed at nineteen years old in Chicago:

Lord, you know that the first body I seen

Laying in the intersection was the body of a good friend

We called him Twan

The same nineteen I was

All still but runny

Broken marionette

Watchin him own breath exit him body

Off the corner of North Avenue and Central

All the trucks and cars him body paused

Right before my eyes

My friend Twan turned into dead

A crossin’ guard haltin’ traffic

The juxtaposition of various performance modalities (anecdote, sermon, narration), media (video, live narration, text) and highly localized allusions provocatively fleshed out the libretto’s “ephemeral and invisible materiality,” which significantly reshaped audiences’ understanding. [78] The unique treatment of the libretto as creative material not only contributed to a chronotopic experience, but also served as a reminder that it can be approached from multiple angles: musical text, historical document, anecdote, poetry, and literature.

But we are still left with this conundrum: both Music and young had actual creative agency in both productions. How do we analyze, hear, understand, or salute the agency of the two Black poets who contributed to both productions in such radically different ways? More pointedly, how do we reconcile Music’s role as Erda with young’s rendition of The Norns? Collaborating with both artists was undoubtedly a key strategy for the creative team to “de-politicize” Wagner’s problematic legacy. [79] Despite their best intentions and hopes, they had found uneven success through such collaborations. young’s virtuosic performance effectively destabilized Wagner’s original libretto by coming up with a powerful counter-narrative deeply rooted in—and inseparable from—Chicago’s history. Music, however, risked falling back on historical stereotypes of Black women, thus undercutting the creative team’s progressive intentions. Far from displaying irreconcilable differences, these artistic departures could instead be reconceived as windows into the hold of passing time on an opera’s evolving conception, which eventually resulted in a different reception.

My close engagement with Twilight: Gods generated a new understanding of re-enchantment in site-specific opera. Rejecting immersion, I turn to the embrace of mixed media, materialities, and serendipities emerging from unscripted encounters and imaginative associations engendered by the performance in the here-and-now. In scrutinizing the reimagination of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung in Detroit and Chicago, I argue that despite the creative team’s hopes for a racially inclusive future in opera, it has not fully succeeded in meeting the redemptive terms it has set for itself. Though young’s virtuosic transmedial performance resonated with local audiences, Music’s hypersexualized performance of Erda, and the commodified packaging of Motown in Scene 4, gesture toward a display culture more interested in optical and musical representation than in reflecting true diversity of creative Black voices.

Instead of thinking that visible and audible representations are identical to, signify, or even contribute to social progress and antiracism, opera companies must continue working towards prioritizing voices from the Black community, and towards opposing the desire for display culture, a desire that always comes at the expense of true aesthetic esteem. To produce an opera with an American perspective on American music, we must fully acknowledge and center Black music and engagement in all stages and phases of the conception, production, performance, and reception, as well as account for diversity among its singers, designers, composers, performers, and board. Only then can the process of creative collaboration truly reflect the successful decolonization of opera.

[*] I would like to express my gratitude to Professors Carolyn Abbate and Kate van Orden of Harvard University, who have seen the idea of this article move through various stages and who provided me with many valuable critiques in feedback along the way. This article is dedicated to both of you. Special thanks are also due to Professors Giorgio Biancorosso and Emilio Sala, editors of Sound Stage Screen, who shepherded this article from start to end, and the anonymous reviewers who offered helpful remarks on this article. Earlier versions of this project were presented at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Musicological Society in Chicago (online) and the 5th Transnational Opera Studies Conference in Lisbon in July 2023. I am also grateful toward Yuval Sharon for sharing with me in-house recordings of the Detroit production of Twilight: Gods.

[1] Insights gained from the Detroit production were drawn from an in-house videotaping that Yuval Sharon shared with me, which was not disseminated to the public, while the Chicago production was made available on YouTube for a limited period of time.

[2] The Industry describes itself as “an experimental company that expands the operatic form” as shown on its webpage. See The Industry, website, accessed October 11, 2023.

[3] Yuval Sharon, Zoom Resvés Opera - Session with Yuval Sharon, interview by João Pedro Cachopo and Luis Soldado (December 6, 2020). See Centro de Estudos de Sociologia e Estética Musical, “Resvés Ópera #2,” YouTube video, uploaded on June 01, 2021.

[4] See Detroit Opera House, “In Conversation: On Wagner’s Ring,” YouTube video, uploaded on October 15, 2020.

[5] Detroit Opera House released a five-minute orientation video in which Sharon explains to audiences the logistics of the performance. See Detroit Opera House, “Twilight: Gods, Drive-Thru Opera Instructional Video,” YouTube video, uploaded on October 13, 2020.

[6] Detroit Opera House, “In Conversation.”

[7] David Levin discussed the “unsettling” possibilities that operatic stagings bring to opera, an already “unsettled” genre. I am borrowing his term in my article to illuminate how site-specific operas, far from replicating the operatic narrative, generates even more competing perceptions and interpretations in both the performance and production. See David J. Levin, Unsettling Opera: Staging Mozart, Verdi, Wagner, and Zemlinsky (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007); Also cited in Megan Steigerwald Ille, “Bringing Down the House: Situating and Mediating Opera in the Twenty-First Century” (PhD diss., University of Rochester, 2018), 6.

[8] Edward W. Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places (Malden: Blackwell, 1996), 5–6. Soja provides a thorough summary of the theorizations and debates of “thirdspace” put forth by notable thinkers such as Henri Lefebvre and Michel Foucault, the former focusing on “lived spaces of representation” while the latter foregrounding “the trialectics of space, knowledge, and power” in his notion of heterotopia (15). See Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991); Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” trans. Jay Miskowiec, diacritics 16, no. 1 (1986): 22–27.

[9] In June 2020, the Deutsche Oper Berlin deployed their opera house’s car park to stage Wagner’s Das Rheingold, albeit a ninety-minute rendition with a significantly reduced orchestral force. And in December 2020, Opera Santa Barbara staged Carmen as a “Live Drive-In” experience at the Ventura County Fairgrounds.

[10] The singers still performed on elevated stages, and audiences still sat either on chairs or in cars.

[11] A nuanced consideration of access and equity must account for the financial situations of Black communities in Detroit and Chicago. In Detroit’s case, since the 1960s, overseas industrial competition and local socioethnic tensions have led the city into rapid de-industrial decline and widespread unemployment, with its local Black community hit the hardest. As David Morris asserts, underneath the mass consumption of Detroit always hid inequalities fueled by “American ideologies of expansionism and consumerism by elites.” These inequalities, alongside issues of access, are cast into sharper relief in Twilight: Gods as one considers the disproportionate gap between a high proportion of Black actors represented among its performers and the low attendance of the opera by the local Black communities. This is likely attributed to the ticket prices, which are financially oriented toward a middle-class consumer who possesses a car. See Yuval Sharon, “Opera Through the Lens of the Black and Jewish Communities,” The Detroit Jewish News, April 27, 2022; David Z. Morris, “Cars with the Boom: Identity and Territory in American Postwar Automobile Sound,” in “Shifting Gears,” special issue, Technology and Culture 55, no. 2 (2014): 333.

[12] Site-specific operas produced by The Industry have drawn much attention from scholars such as Megan Steigerwald Ille and Jelena Novak. More recent literature on Invisible Cities and Sweet Land can be found respectively in Megan Steigerwald Ille, “The Operatic Ear: Mediating Aurality,” Sound Stage Screen 1, no. 1 (2021): 119–43, and Jelena Novak, “Sweet Land, a New Opera by The Industry,” Sound Stage Screen 1, no. 1 (2021): 275–83.

[13] Upon seeing the drive-through productions generate rave reviews from audiences, James Darrah, the new artistic director of Long Beach Opera, followed suit and conceived a drive-in production of Philip Glass’s Les Enfants terribles in May 2021 with added English narration.

[14] Audiences of both operas experienced what James Wierzbicki calls “wrapped” listening, which he defines as a form of listening that “we likely take for granted when we encounter them in our everyday lives but which we tend to celebrate when they are artificially re-created by stereophonic audio systems.” See James Wierzbicki, “Rapt/Wrapped Listening: The Aesthetics of ‘Surround Sound’,” Sound Stage Screen 1, no. 2 (2021): 102–3.

[15] In Hopscotch, audiences chose one of the three routes, each of which took them all across LA like a typical road trip. The windshield became the cinematic frame through which audiences viewed the performance, and automobility served as the means for them to enjoy the performance. In Twilight: Gods, audiences followed the path choreographed by the parking complex and were instructed to tune in to different radio channels as they ascended through the levels, though the creative team could have just broadcast the whole event on one frequency. Clearly, the act of retuning served as a form of techno-magical caesura by using irrational rituals to play on spectators’ habits, leading them to willingly suspend disbelief while caught up in technical play. More in Sharon,“Resvés Ópera #2.”

[16] See Gundula Kreuzer, Curtain, Gong, Steam: Wagnerian Technologies of Nineteenth-Century Opera (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018).

[17] “TWILIGHT: GODS,” Detroit Opera, official website, uploaded on October 17, 2020.

[18] In discussing The Industry’s Hopscotch, Steigerwald Ille posited that the “physical spaces—which seem to exist simultaneously within past ‘movie worlds’ and the reality of an urban city—validated audience members’ feelings that they themselves are also part of a quasi-cinematic experience.” See Steigerwald Ille, “Live in the Limo: Remediating Voice and Performing Spectatorship in Twenty-First-Century Opera,” The Opera Quarterly 36, no. 1 (2021): 12.

[19] Steigerwald Ille, “Live in the Limo,” 13.

[20] See more in Meredith C. Ward, “The ‘New Listening’: Richard Wagner, Nineteenth-Century Opera Culture, and Cinema Theatres,” Nineteenth Century Theatre and Film 43, no. 1 (2016): 88–106.

[21] See Nina Sun Eidsheim, Sensing Sound: Singing and Listening as Vibrational Practice (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), 58–94; Steigerwald Ille, “Bringing Down the House,” 73–116.

[22] See Kreuzer, Curtain, Gong, Steam.

[23] Gundula Kreuzer, “Steam,” in Curtain, Gong, Steam, 162–214.

[24] Kreuzer further makes us question the various nineteenth-century personal accounts of audiences who attended Wagner’s music dramas and remarked on their hypnotic experiences. How much is fictionalized or romanticized?

[25] More on Wagnerian phantasmagorias, the earliest “wonders of technology,” in Theodor W. Adorno, “Phantasmagoria,” in In Search of Wagner, trans. Rodney Livingstone, new edition (London: Verso, 2005), 74–85. Adorno posits that the deliberate concealment of labor and the source of production gives rise to illusion and the experience of magic.

[26] Carolyn Abbate, “Wagner, Cinema, and Redemptive Glee,” The Opera Quarterly 21, no. 4 (2005): 602.

[27] Estela Ibáñez-García exemplifies how “witnessing the workings of illusion strengthens its grip on us” in her extended examination of Ingmar Bergman’s The Magic Flute (1975). She argues that the unveiling of the artwork’s artificiality, far from hindering audiences’ engagement with film, enhances “engrossment with its magic.” See Estela Ibáñez-García, “Displaying the Magician’s Art: Theatrical Illusion in Ingmar Bergman’s The Magic Flute (1975),” Cambridge Opera Journal 33, no. 3 (2021): 197, 211.

[28] While attending the performance of Invisible Cities, Eidsheim asserts that she heard sounds she did not see when she was plugged into “the omnisonorous sound world” of the headphones. See Eidsheim, Sensing Sound, 84.

[29] Eidsheim, 58–9.

[30] Katherine Ellis echoed this view in reference to open-air opera, positing that it “was not just site-specific in the sense of performance environment, but in that of audience experience. It was another entertainment alongside processions, street dancing, and festive banquets. As such it was more of an outing than an event. The journey, lead-up, and return were as important as the event itself ” More in Katherine Ellis, “Open-Air Opera and Southern French Difference at the Turn of the Twentieth Century,” in Operatic Geographies: The Place of Opera and the Opera House, ed. Suzanne Aspden (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2019), 192.

[31] Sharon, “Resvés Ópera #2.” This brings to mind Eidsheim’s discussion of her 2013 experience at Union Station in LA for Invisible Cities: “multiple layers of the city are already invoked and activated for and by audience members before and after their arrival.” Eidsheim, Sensing Sound, 82.

[32] Geographer Yi-Fu Tuan addresses the gap between one’s assumptions of a place, which is built upon “abstract knowledge” about it, and one’s experience of it, which “takes longer to acquire” for it comprises “a unique blend of sights, sounds, and smells, a unique harmony of natural and artificial rhythms.” More in Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001), 183–4.

[33] It must be noted, though, that the use of Kuroko-like figures is not unprecedented. Patrice Chéreau also used them in his 1976 production of the Ring, but Sharon deployed them in much more radical ways in Twilight: Gods.

[34] Keren Zaiontz, “Ambulatory Audiences and Animate Sites: Staging the Spectator in Site-Specific Performance,” in Performing Site-Specific Theatre: Politics, Place, Practice, ed. Anna Birch and Joanne Tompkins (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 168. Zaiontz’s notion of audiences as “doubled subjects” co-creating the performance is also cited in Steigerwald Ille, “Live in the Limo.”

[35] Abbate, “Wagner, Cinema, and Redemptive Glee”: 602–3.

[36] Michigan Opera Theatre, “TWILIGHT: GODS TEXT AND TRANSLATION,” 2020.

[37] This notion of an ephemeral flaw being documented in a permanent form via a wrong medium, which enables one to reflect on issues of production and the efficacy of sound, is stimulated by Carolyn Abbate’s push for scholars to be more attentive to pure materiality and the physicality of performance, as a way into philosophical provocations of various kinds. Resisting reading-as-cryptography in which demystification or identification becomes “the default condition for humanists engaged with works and texts,” Abbate instead focuses on “the textures and the physicality they convey” and advocates for scholars to shift their attention from closed interpretation to open-ended expressive possibilities. More in Carolyn Abbate, “Overlooking the Ephemeral,” New Literary History 48, no. 1 (2017): 79–80.

[38] Melle Jan Kromhout, The Logic of Filtering: How Noise Shapes the Sound of Recorded Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 13; italics in the original. This also reminds us of Eidsheim’s experience at Invisible Cities. She describes hearing the performer’s voice “with more strength and presence from the headphone signal than from the acoustic transmission,” and further elaborated, “I finally understood that acoustics offers more to us than delivering optimal sound and optimizing sound. I learned that acoustic and spatial specificity also take part in giving form to the figure of sound.” See Eidsheim, Sensing Sound, 58–59.

[39] This view resonates with Jonathan Sterne’s discussion of listening practices that telegraph operators adopted in the 1850s. The operators discovered that they could “discern messages” more efficiently by listening to the “noise that began as a by-product of the machine’s printing process,” which gradually, over time, became “its most important aspect.” See Jonathan Sterne, The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 147.

[40] Wierzbicki, “Rapt/Wrapped Listening,” 102.

[41] Here again, I am borrowing David Levin’s use of the term “unsettling.” See Levin, Unsettling Opera.

[42] Holly Rogers, “The Audiovisual Eerie: Transmediating Thresholds in the Work of David Lynch,” in Transmedia Directors: Artistry, Industry and New Audiovisual Aesthetics, ed. Carol Vernallis, Holly Rogers, and Lisa Perrott (New York: Bloomsbury Academic & Professional, 2020), 265.

[43] This disorienting sensation speaks more broadly to other technologically mediated site-specific performances as well, as observed in Eidsheim’s experience at the performance of Invisible Cities. She described feeling “two simultaneous acoustic worlds rub up against each other,” one occupied by the physical acoustic space, and the other provided by the headphones. See Eidsheim, Sensing Sound, 89.

[44] Siegfried is played by tenor Sean Panikkar who is of South Asian descent. Goerke and Martin, who play Brünnhilde and Waltraute respectively, are white.

[45] The character Erda of course does not appear in Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, having exited the Ring in Siegfried Act 3.

[46] To illustrate, Ryan Ebright elaborated that in the Pulitzer’s history, “jazz” is at times used as “a ghettoizing designation,” which speaks to people’s perception of Black music as a lower art form than art music. More in Ryan Ebright, “Anthony Davis’s Revolutionary Opera: ‘X’,” The New Yorker, May 22, 2020.

[47] Naomi André, Black Opera: History, Power, Engagement (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2018), 24. Notable examples of Black operas in the 20th century include William Grant Still’s Troubled Island (1949) and Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha (1972). More recent Black operas include Daniel Schnyder’s Charlie Parker’s Yardbird (2015), Nkeiru Okoye’s Harriet Tubman: When I Crossed that Line to Freedom (2014), Daniel Sonenberg’s The Summer King (2017) on baseball legend Josh Gibson, Terence Blanchard’s Champion (2013) on American boxer Emile Griffith, and Anthony Davis’s The Central Park Five (2019). See Ebright, “Anthony Davis’s Revolutionary Opera: ‘X’.”

[48] See Ebright.

[49] See Matthew D. Morrison, “Race, Blacksound, and the (Re)Making of Musicological Discourse,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 72, no. 3 (2019): 781–823. Though Morrison’s work does not feature prominently in opera studies, his concept of Blacksound nonetheless proves extremely valuable in analyzing site-specific performances like Twilight: Gods in the context of today’s neoliberal era, particularly as we consider where the boundary is between honoring the specificity of a site and unwittingly playing into commodified expectations.

[50] Dylan Robinson, Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020), 8.

[51] Integrating Black culture in a Western operatic frame recalls Peter Sellars’ 1987 production of Don Giovanni, which is set in a racially mixed American ghetto. Though vastly different representation of Black culture are presented—Sharon’s Twilight: Gods adopts a celebratory approach towards Motown music while Sellars’ Don Giovanni resorts to derogatory stereotypes of the Black community—it is nonetheless productive to place both “updated” productions alongside each other in illuminating the irresolvable clash between Western art music and the reductive employment of Black culture.