ARTICLE

From LP to Screen: Tito Schipa Jr.’s Orfeo 9 (1973–1975) *

Daniele Peraro

Sound Stage Screen, Vol. 3, Issue 2 (Fall 2023), pp. 47–75, ISSN 2784-8949. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. © 2024 Daniele Peraro. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54103/sss20776.

On the evening of 8 February 1975, Orfeo 9, a film musical, was aired for the first time on RAI 2, a channel of the state-owned Italian public television company. The film was written, directed, and performed by Tito Schipa Jr. (son of the famous tenor) and produced for television by Programmi Sperimentali Rai. The earliest example of an Italian rock opera on the small screen, Orfeo 9 is a modern reworking of the Orpheus myth.

In Schipa’s version, Orfeo is a young hippie living peacefully but unhappily in a commune relocated in a deconsecrated church far from the heavily industrialized, alienating space of the city (the latter is a representation of Hell). A “Vivandiere” (Sutler) arrives from the city with a sack of bread and urges Orfeo to play the guitar to find happiness. Orfeo obliges, Euridice appears, and our protagonist falls in love with her. The couple is united in a pagan marriage ceremony but the idyll is broken when the “Venditore di Felicità” (Happiness Vendor) arrives and deceives Orfeo, selling him ephemeral happiness in the form of a dose of drugs. Not recognizing true happiness in Euridice, Orfeo falls under the spell of the Venditore. Euridice disappears, kidnapped by the diabolical Venditore. Orfeo is thus forced to leave his communal paradise and enter the infernal city to rescue his bride. During his journey, he is confronted with many of the horrors of the contemporary world (such as the threat of an atomic war). Crushed by its diabolical machine, Orfeo does not make it out of the city alive. As in many other twentieth-century adaptations of the classical myth, in Orfeo 9 the Orpheus figure is no longer a god but a man like any other tormented by anxiety and doubt. [1]

I should say at the outset that Orfeo 9 is the title of three different works: a play, a double LP, and the resulting feature film. The film is an adaptation of the theater play staged at the Teatro Sistina in Rome in 1970 but it is above all a remake of the double LP released in 1973 (also signed by Schipa). The record was conceived as a commemoration of the theatrical performance; yet it was released as a stand-alone product. It was framed as the soundtrack of a new “pop opera,” as Schipa called it: a single work iterated in different media. The film was shot in color in 16mm format and produced by Programmi Sperimentali Rai in order to be televised. Its broadcast was aborted by RAI’s executives in 1973. In his memoir Orfeo 9 – Then an Alley , Schipa states that someone in the board of directors of RAI did not understand the film’s overarching aim. The image of a syringe and the preparation of a dose in a key scene of the film was viewed as problematic, and Orfeo 9was accused of promoting synthetic drug use. [2] However, Orfeo 9was aired in black and white two years later (in 1975). It was subsequently blown up to 35mm format by the distribution company DAE (Distribuzione d’Arte e d’Essai) and shown in university auditoriums and avant-garde cinemas. Over the years, Orfeo 9 became and to this day remains a cult film for fans of rock music and 1970s culture alike. The stage musical, the double LP, and the film are linked by a single ideation and production process, which began with the theater performance and culminated in the filmic adaptation. Nevertheless, Schipa notes, the three iterations are distinct and autonomous products. [3]

In light of the above, how to define the film Orfeo 9: a filmic adaptation or a television adaptation? As mentioned, it was shot in 16mm but conceived for television. Therefore, both definitions may be correct. I nevertheless prefer to use the term filmic adaptation, for the film earned a reputation that resonated long after its TV première.

Unlike a conventional musical or animated film, the filmic adaptation was aired as a visualized version of the record. In the former, the prerecorded voice and orchestral tracks are tied to the production of the film per se. Without the film, the soundtrack would not exist. By contrast, the Orfeo 9 double LP was—and still is—a stand-alone product from which a film was made. The album is strictly speaking not a soundtrack.

Schipa himself declared that the film was almost entirely a by-product of the record, and not only in the chronological sense. He recalls the beginning of his idea for a film adaptation with these words:

I began to understand that the idea of turning Orfeo 9 into a film was certainly alluring, but that in reality the drivers of the action had to be changed: it should not have been a film with that soundtrack, but instead, a soundtrack from which to create a film. The images were suggested by the music, in short, and not the other way around. [4]

Schipa’s words invite us to reflect on the relationship between video and audio as one between a film and a recorded album. His intention was to rewrite the detailed theatrical performance as a record, which would later become a film, “forcing the narrative to focus its rhythms according to the patterns of a pop music record.” [5] Thus, the LP became the starting point for the making of the film. But Schipa also wanted to compose an audio track that could be an object with a life of its own. [6] The work of arranging and rewriting the music was entrusted to the Italian-American composer Bill Conti, who a few months earlier had arranged the tracks for Schipa’s EP Sono passati i giorni/Combat (1971). [7]

Schipa conceived the pop opera based on the length of a double LP. At less than 25 minutes per side, its length could not therefore exceed a hundred minutes. [8] Furthermore, the opera was structured so that each side contained a complete part of the story. The A-side of the first record contains the introduction of the opera up to the presentation of Orfeo, while the second side recounts the story of his life in the commune up to his marriage to Euridice. The finale of the first act coincides with the last track of the second side of the first record; consequently, the first side of the second record begins with the piece that introduces Orfeo’s journey as he leaves his retreat to save his bride. Perhaps Orfeo 9is subtitled “opera pop,” at least in part, because it is enclosed in a popular format for music: a record.

As a by-product of the album, the film had to be adapted to the rhythms and pacing of the record format. The relationship between image and sound thus took on a special significance. Critic Renato Marengo has emphasized the defining characteristic of Schipa’s modus operandi thus:

The image–sound pairing is one of the greatest merits of Orfeo 9. In essence, it is the first Italian experiment with a visualized soundtrack, and that is no small feat when you consider that normally a film is first written, performed, and filmed; then, a soundtrack is added. Here, the reverse was done: images were superimposed onto a soundtrack. [9]

It is best to rephrase the notion of a “visualized soundtrack” as visualized album, however, in order to mark the distance that exists between Schipa’s project and the soundtrack production process of a conventional film musical. The merit of Marengo’s quote lies in the suggestion that we consider the relationship between two types of media. Already in the first phase of recording, the relationship between the two media created the need to make strategic choices. With regards to the voices of the singers, for example, Schipa recounts: “I had to keep in mind that the final product was a film. I wanted whoever played a lead role on tape to play that role also on film … I wanted the audience to know that this was the complete cast. No tricks.” [10] As an acknowledgement of this choice, the film’s credits read: “Tutti hanno cantato con la propria voce” (Everyone sang with their own voice). Schipa decided that the choice of vocal performers depended on two factors: first, singing skills; second, compelling stage presence and acting talent. The look of someone whose voice seemed ideal on record might not meet the demands of a film. It was the cinematic image that dictated the choices made for the record. For example, the character of the hitchhiker, played on stage by Giovanni Ullu, who had an ideal voice but was not a professional actor, was entrusted in the film to Roberto Bonanni, a photogenic singer who had already played Claude in the Italian theater version of the musical Hair (1970). Despite Schipa’s declaration of intent, it was not always possible to have the actors sing with their own voices. Ullu for example, lent his voice to a minor character at the beginning of the film (a young member of the commune).

Building on Marengo’s suggestion, I invert the oft-asked question of what pop music can bring to cinema. Instead, I ask what cinema can bring to a record. Focusing on three moments of the film, I investigate how Orfeo 9 contributed to “shaping the experience of song,” to cite film scholar Claudio Bisoni’s words with reference to the musicarello film genre. [11] As Raymond Knapp notes with regards to the process of re-creating performances across media, “at each stage within this layered process of remaking and performance, identities are conceived and reconceived, formed and re-formed, and, above all, performed, which is a matter of both assimilation and self-invention.” [12] I begin by framing Orfeo 9’s double LP in the Italian and international popular music context, in particular the rock operas of that era. Next, I consider the functions of images for music identified by Bisoni as the key to interpreting the scenes I have selected. In keeping with Knapp’s suggestion to move musical theater studies toward a more performance-centered methodology, I link these images to the categories of liveness and audio-video synchronization, the actors’ gestures, and music, as theorized by Paul Sanden and Michel Chion (among others). [13] This leads me to analyze what film language can offer to the listening experience. Building on Sergio Miceli and Rick Altman’s interpretations of the film musical, I show how Schipa’s embrace of a novel type of relationship between sound and image is the fulfillment of the genre’s potential for self-renewal. Through both the recording and the film, Schipa rewrote the fable of Orpheus for a cross-media context.

Orfeo 9 between Rock Operas and Italian Concept Albums

If “musical theater is popular music,” as Jake Johnson points out in his introduction to Divided by a Common Language, [14] then the study of Orfeo 9 is a great opportunity to include the Italian context in the growing debate about popular music and its intersection with the musical. As Kevin J. Donnelly points out, the visualized concept album is an aspect of the recording industry rather than the film industry and, for this reason, it needs to be studied in its relationship to the former. [15] In The Evolution of the Original Cast Album, George Reddick states: “Changing ideas of what an album could be during the late 1960 had a profound effect on the role of Broadway cast recordings.” [16] In 1967, The Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band , defined by critics as the first concept album in rock history. Although critics and scholars disagree on whether it inaugurated or merely consolidated a new genre, The Beatles endorsed a new phase of artistic experimentation, assisted in part by the new opportunities provided by new recording technologies. While previously the pop record was contingent on corresponding live performances, with the arrival of the concept album the LP began to be considered as the artist’s final goal. [17] Reddick highlights a further shift in the relationship between album and live performance. Two years after the release of Sgt. Pepper’s, the single Superstar (1969) by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice came out. The double LP concept album Jesus Christ Superstar was released following the success of the single. In 1971, in turn, the Broadway musical production of the same name opened as a result of the album’s huge success. [18] The album was no longer the final product, the document of a performance, but the starting point of a process that would lead to stage a musical.

During the mid-1960s, the evolution of the studio recording process led to the introduction of the multitrack tape, which, as Julie Hubbert observes, “dramatically expanded the ability to create a more complex sound landscape.” [19] In the following years, multitrack technology changed the way musicians and recording engineers conceptualized their work. Songs were constructed and assembled in the same way films were edited. As Elizabeth Wollman notes, “concept albums are for the most part studio creations.” [20]

Schipa says he wanted to give the record a cinematic idea. During the editing process of the LP, the eight-track machine allowed Schipa to construct a soundscape by selecting different parts and adding echo effects, noises, manipulating voices and sounds in order to lend “different colors” to the final product. [21] For example, in the final track of the first LP, infernal voices are constructed by using a reverse tape effect and mixing them with the sound of the wind. This solution evokes a desolate and disturbing sonic place, visualized in the film as empty rooms with no doors or windows, and the tribe boys curled up in fetal positions.

At this point, it is necessary to clarify the terminology used to refer to the recording of Orfeo 9. Roy Shuker points out that concept albums and rock operas are collections of songs “unified by a theme, which can be instrumental, compositional, narrative, or lyrical.” [22] In Grove Music Online, John Rockwell writes: “‘Rock operas’ grew out of ‘concept albums,’ LPs with a theme, in the mid-1960s, and hence are really closer to the song cycles of classical tradition than to opera,” and he notes that “some of the more interesting examples were never intended for live performance.” Rockwell also notes that rock operas are “part of the far larger alternative tradition of music-theater works.” [23] The relation to music theatre might explain the difference between rock operas and the concept album. Yet it remains difficult to define a clear difference between the two genres; how we label a work depends on many, overlapping factors (such as how musicians describe their LPs, their sources of inspiration, and the cultural and artistic context of production).

In our case study, Schipa states that he drew inspiration from the English rock opera, in particular The Who’s Tommy (1969). Nevertheless, Orfeo 9 has more in common with another English rock opera of those years, one that is rarely mentioned by Schipa, namely Jesus Christ Superstar (1970). Firstly, both operas draw on well-known mythic-religious stories made modern through avant-garde staging and the use of rock music. Secondly, unlike Tommy, whose music is performed only by The Who themselves, Orfeo 9 and Jesus Christ Superstar are sung-through operas performed by a classic rock ensemble (drums, bass, guitar, keyboards) supported by a symphony orchestra. In Tommy, the lead singer Roger Daltrey plays all the characters of the story, while in both Jesus Christ Superstar and Orfeo 9 each role is performed by a different singer. Tommy, too, differs from Orfeo 9 and Jesus Christ Superstar because The Who did not initially intend to create a musical out of the concept album. [24] Although Orfeo 9 was staged at Teatro Sistina, the starting point for the film adaptation was the LP. For all these reasons, Schipa defines Orfeo 9 as an “opera pop” or “opera rock.” [25]

In Italy, between the late 1960s and the early 1970s, the concept album remained the exclusive domain of singer-songwriters such as Fabrizio De André. In those years the world of Italian popular music was undergoing a sea change. Singer-songwriters were the first to realize that the singles market was running out of steam and that the long-playing could be a commercially more viable format. As it turned out, the concept album became a widespread format not only for singer-songwriters but also for progressive rock bands such as Banco del Mutuo Soccorso and Premiata Forneria Marconi. [26]

Orfeo 9 differs from Italian concept albums of the time in that the tracks moved beyond the song form. Until the late 1960s, concept albums in Italy consisted of a string of songs that, although linked by a concept or narrative theme, were not musically related to each other. From the beginning of the next decade, artists, especially those associated with the prog scene, attempted to link tracks musically as well. Orfeo 9 can be seen as an intermedial effort to push the boundaries of the song in the direction of the film soundtrack. Due to the fast evolution of recording technologies, those years saw not only the consolidation of the bond between studio song and film editing but also the cross-pollination of their aesthetic principles and narrative forms. On the one hand, drawing on the example of the concept album, artists subsumed song composition under the development of a narrative. On the other hand, cinema began to move more and more toward popular music. I now turn to three examples of this convergence in as many scenes of Orfeo 9.

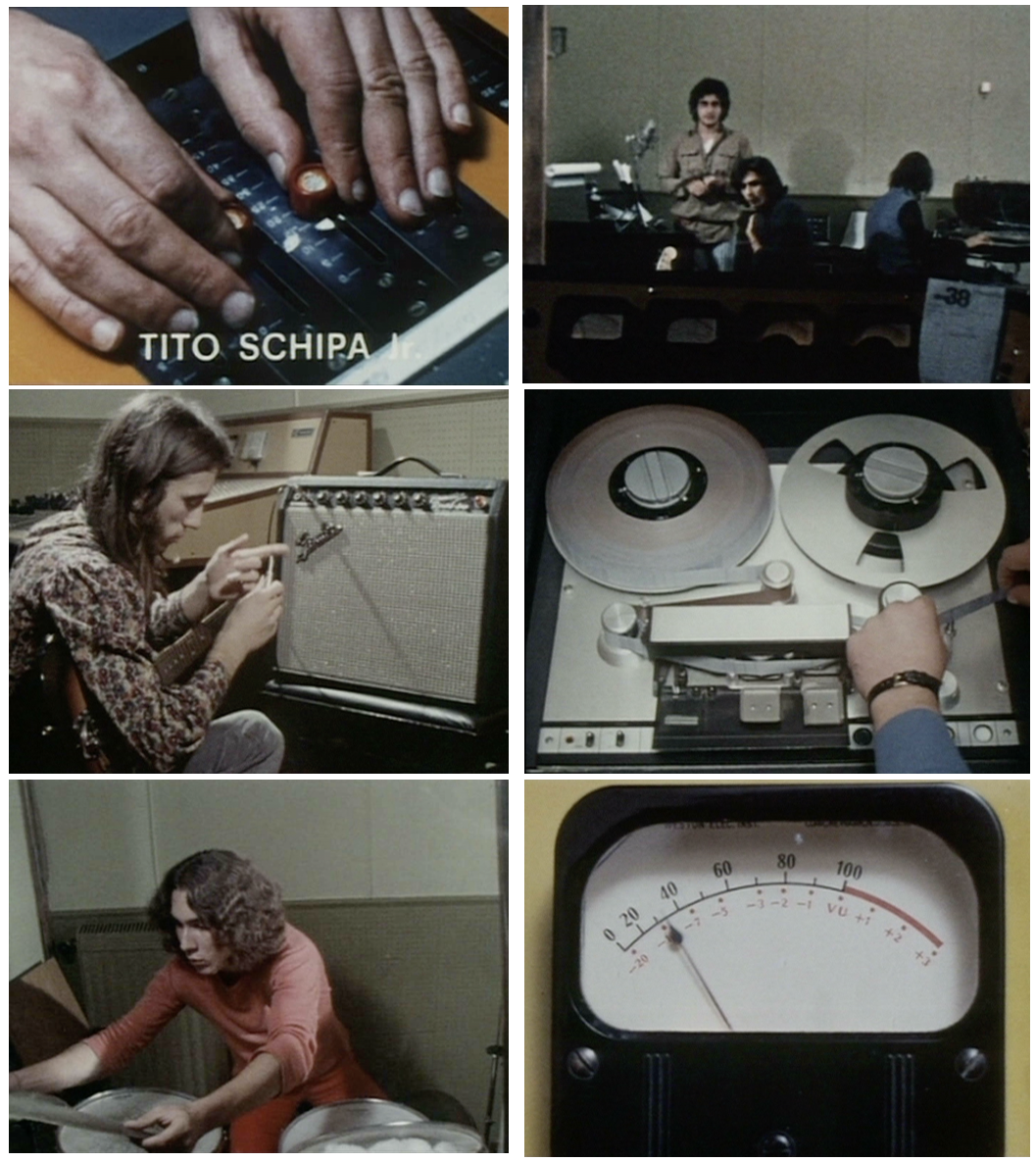

I begin with a segment from the opening scene, set in a studio where Schipa and his band, playing themselves, are preparing to record the opera. [27] The drummer sits on his stool, while a cut takes us to a close-up of the young Schipa speaking into a microphone; the audio, however, is muted at this point. The opening credit reads: “Un film scritto, musicato e diretto da Tito Schipa Jr.” (A film written, set to music, and directed by Tito Schipa Jr.). Simultaneously, the mixer “opens” the audio to Schipa, saying “Tito, parla” (Talk, Tito) to test the volume levels. There follows a close-up of two hands turning up the volume on the console. Now the viewer, too, can hear what is happening in the recording studio. As the frame widens, we notice that Schipa is standing next to music director Conti on the piano, the drummer, and the organist. They start rehearsing. The silhouette of the mixer adjusting the sound is in the foreground, backlit. Finally, an ensemble of shots survey the preparatory stages of the session, the camera pausing to show a few details of the equipment and instruments being used.

This fictional recreation has the function of evoking a live performance: the “here and now” of a group of artists gathering in a studio to record a pop opera. The scene opens with the image of a piece of magnetic tape being hooked up to the tape recorder and then lingers on the microphones, amplifiers, and other equipment being readied by the musicians. These images are consistent with the remediation of pop/rock performances in film, particularly the music docufilms and musicarelli (Italian musical films produced for young audiences) of those years. But above all, the scene introduces us into a meta-cinematographic or better, meta-discographic sphere in which the recording and the film are mutually implicated: the fable of Orpheus is narrated as if it were a dream evoked by this musical session. From within the recording studio, a choir of three Narrators—who will then become bona fide characters—intervenes by commenting on the story.

Fig. 1 – Still frames from the opening scene of the film.

Music-making plays a fundamental role in the entire film. To describe performance, I prefer to avoid the diegesis/non-diegetic opposition. [28] Given how the story of Orpheus is narrated in the film, it’s possible to trace a demarcation between the real world of the recording studio and the fantastic, dreamed world of the fairy tale. Building on Rick Altman and Jane Feuer’s distinction between fantasy and reality in the film musical, I use the terms “dream” or “fantasy” to indicate the Orpheus fable, a separate imaginary universe with its own rules where protagonists express themselves through song. [29] I reserve the term “reality” for the “here and now” of the recording studio instead.

The introductory images of the film perform what Bisoni describes as a “theatricalizing function” which, by framing the passage as entertainment, “connects the voice to the body.” [30] As Paul Sanden has argued in Liveness in Modern Music, the musician’s body is an increasingly crucial element in live performance. The display of the performer’s body and gestures is a function of what Sanden calls the “corporeal liveness” of the performer—that is, the assumption that “music is live when it demonstrates a perceptible connection to an acoustic sounding body.” [31] This is one of the seven categories of liveness theorized by Sanden that contribute to making a performance, in his words, “authentic.” In the same vein, Simon Frith argues that the musician’s body in a live performance is like an instrument that demands to be seen. [32] By displaying the bodies of the musicians in the studio and anchoring the sounds we hear to their gestures, Schipa sought to recreate the authenticity of rock performance in the context of cinematic fiction.

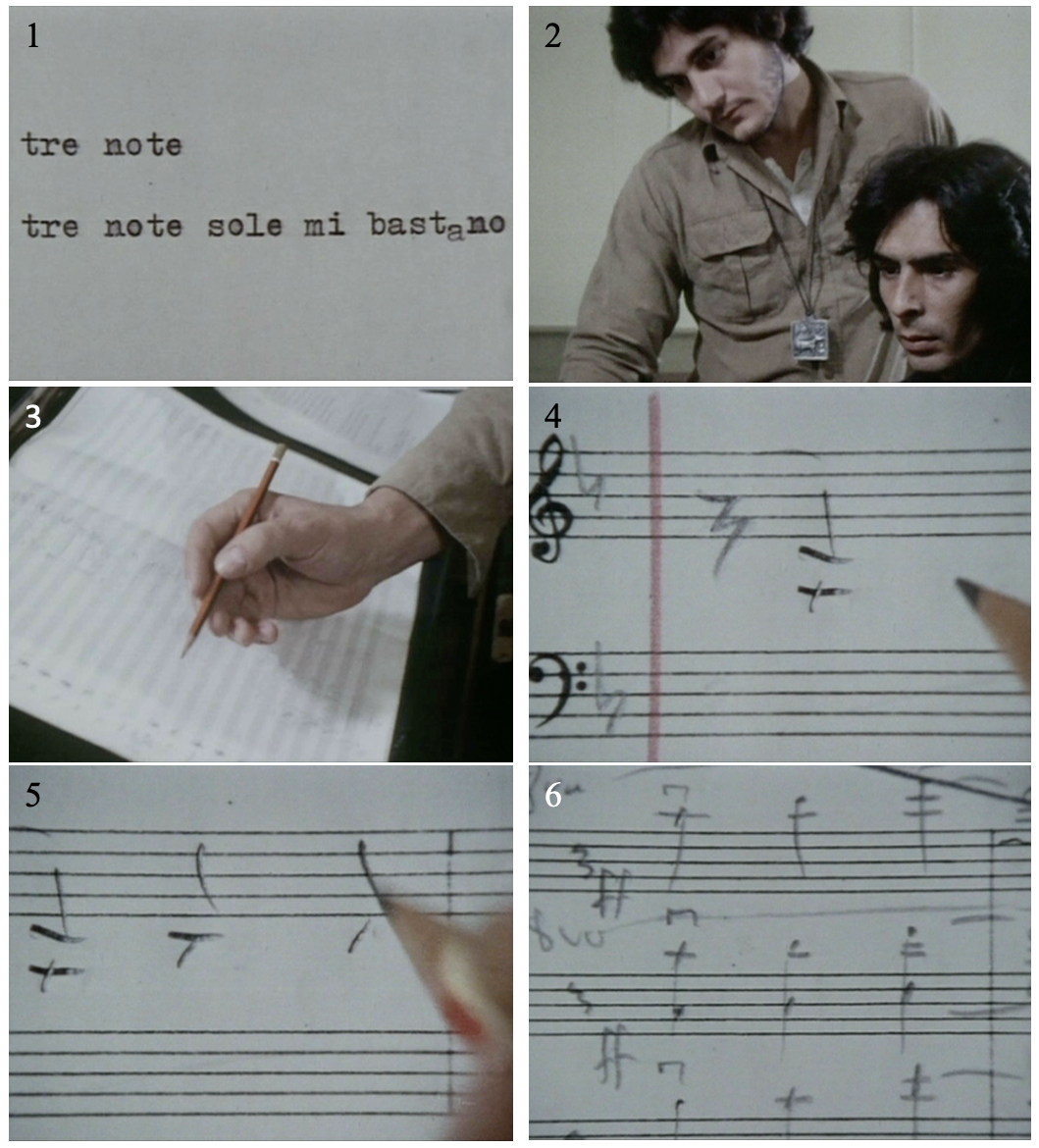

Fig. 2 – Still frames from the first scene of the film, visualization of the beginning of the song “Tre Note.”

In the next segment of the film, following Schipa’s announcement that the first piece to be performed will be “Tre note” (Three pitches), a sign appears with the words “tre note/tre note sole mi bastano” (three pitches/three pitches alone are enough for me) (Fig. 2, frame 1). Schipa approaches the piano (frame 2) and writes on a sheet of music paper the three notes of the overture that open the opera (frames 3, 4, 5). As we see his hand jot down musical symbols on paper, we also hear—in perfect synchrony—the corresponding sounds produced by the Hammond organ. The camera glides over the score and shows the sequence of chords (frame 6), to which the corresponding sound is matched, and then cuts back to the recording booth. The audience hears the music they simultaneously see being notated. The film creates the impression that the music springs from the act of writing.

The images of the performance are synced to the sounds of a pre-recorded soundtrack. Such level of attention to synchronization was by no means a given in the films of those years (whether they were made for television or not). Lip-synching could be imprecise, especially in low-budget productions such as musicarelli but also in films with the same budget as Orfeo 9 . As Maurizio Corbella has argued, filmmakers were less interested in recreating the “here and now” of a live performance than in constructing an ideal space in which the performance took place. [33] In contrast, Schipa felt it was essential that the musicians play in sync to the recording and that during his film the lips on the screen be in perfect synchrony with the corresponding voice tracks.

The title sequence also serves the purpose of establishing the idea of an auteur rock opera. As noted, Schipa introduces himself to the audience as the creator and writer of Orfeo 9 in the opening title. In addition, the mixer refers to him as “Tito”; not as an actor impersonating a character, in other words, but as the author. Secondly, it is from Schipa’s hand as a composer that the opera is born. This idea is reinforced by the fact that Schipa himself plays the role of the protagonist Orfeo, and thus he is at the center of the narrative. In the finale, Orfeo is crushed by the diabolical, infernal machine (a sort of mechanical press) and does not make it out of the city as the same person he was before. Eventually, Orfeo turns towards Euridice, but he does not recognize her. Tellingly, at that moment, Schipa is playing himself. We know this because he is wearing the same clothes he wears in the recording studio scene. As Schipa himself has stated, he does not blame Orfeo’s fatal doubt on the character but rather on himself. [34] In this way, the author Schipa returns to the center of the story, replacing Orpheus at the juncture that is perhaps most strongly associated with the mythical singer. It is at this moment that the idea of a pop opera—composed by a singer-songwriter who must legitimize himself as such within the various media forms and through the modalities of each—is consolidated.

The question of authorship is fundamental to the relationship between the genres of rock and the musical. As Elizabeth Wollman has pointed out, while the musical is conceived as a product of a plurality of authors and professional figures, the myth of authenticity in rock music dictates that the album is produced under the control of a single controlling intelligence, be it an individual, a singer, or a band. [35] The cover of the first version of the Orfeo 9 recording emphasizes the centrality of the singer-songwriter: it shows an extreme close-up of Schipa’s face, his closed eyes made up as if they were open (an idea that Schipa states was borrowed from a photo of the model Veruschka). [36] Schipa’s name appears above the title, while the words “opera pop” appear below. Conti’s name appears in a much smaller font as the orchestrator and conductor. The names of the soloists are not listed. Schipa, then, places himself at the center of the recording as its sole author.

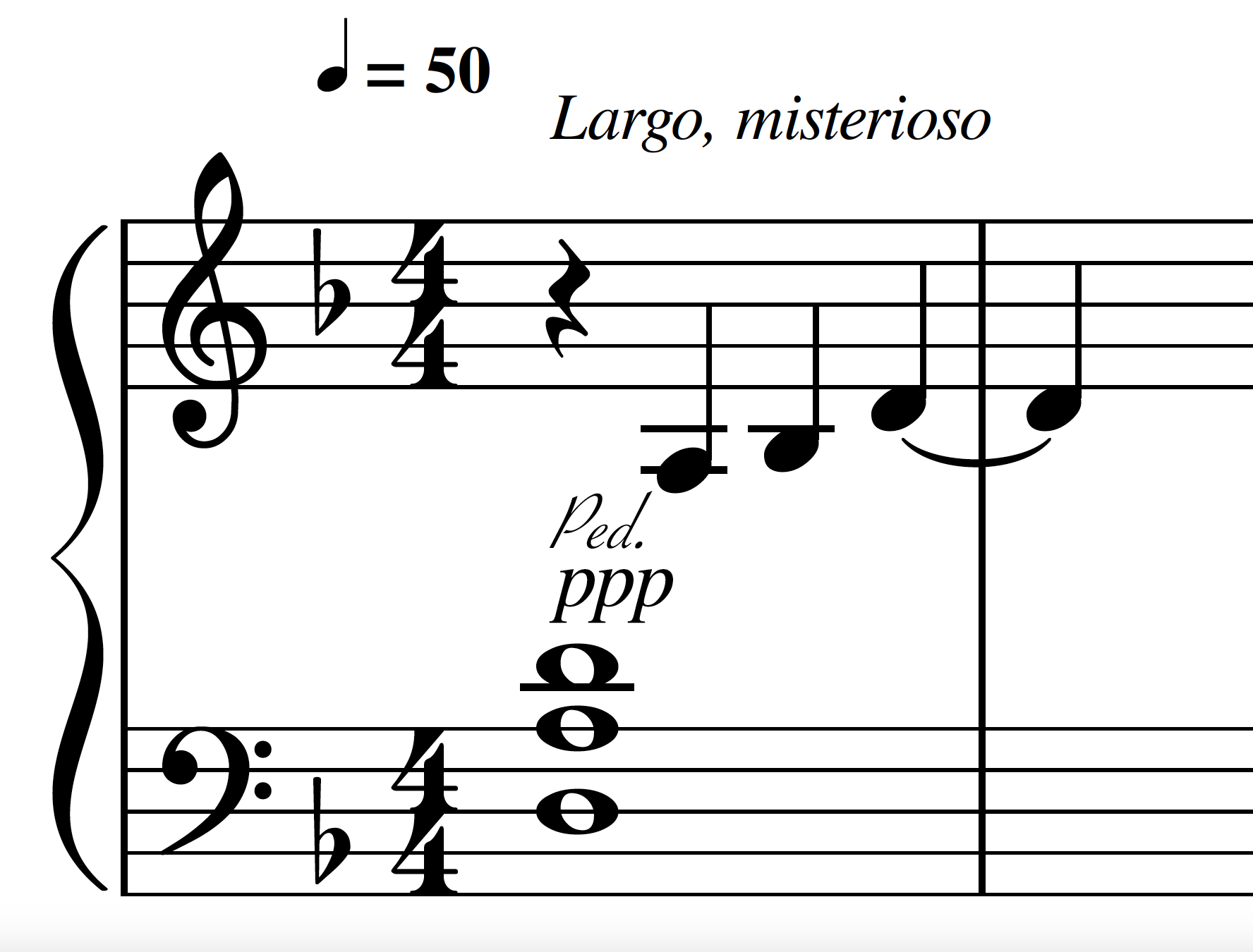

The beginning of the title sequence establishes Schipa’s role in the film in a similar fashion. As Schipa writes the “three pitches,” the soundtrack begins, just as one hears it on the double LP. When listening to the LP, however, we only hear the three pitches; in the film they are also announced by Tito’s signs on a sheet of paper. The images do not merely confirm what we hear but they also underline the dramaturgical and narrative importance of this melodic cell, which is linked to Euridice. The three pitches are all Orfeo needs. These pitches—A, B-flat, and D—are not only the inaugural pitches of the work but they also function as an important musical motif for the opera as a whole.

Fig. 3 – The first bar of the track “Tre Note.”

It is this initial musical cell that gives the piece “Tre note” its name. At first, this first measure is not recognizable as a musical motif in the strict sense of the word but rather as a simple, recurring figure of three pitches. [37] Immediately after its first appearance, this figure is repeated in rhythmic diminution and transposed as an iterated arpeggio by the piano (E – F – A), only to return several times throughout the piece.

Fig. 4 – Excerpt from the track “Tre Note.”

The song “Tre note” is Conti’s arrangement of the introductory number of the theatrical version of Orfeo 9 (whose score was also based on the three notes). Echoing the way in which the three pitches are played by the piano in the overture, in “La ragazza che non volta mai il viso” (The girl who never turns her face), the same sequence of notes is sung by Orfeo in response to the Vivandiere’s question, “E tu cos’hai” (And what’s wrong with you)?

ORFEO

C’è come una stecca che sento nel vento

Una frase incompiuta, una rima taciuta.

Se fosse in amore un silenzio,

Se fosse in un boccio di fiore una brina,

Se fosse…

(I hear a sort of false note in the wind,

An unfinished sentence, an unspoken rhyme.

If might be a silence in love,

It might be a frost in a flower bud,

It might be…)

Although he cannot name his love, Orfeo sings of it. In this sense, the music has the function of anticipating the singer-songwriter’s own realization. Only at this moment in the piece does the musical cell begin to take on precise significance for the attentive listener: the three pitches evoke Euridice, who is the reason for Orfeo’s journey. The beloved thus becomes the driving force behind the entire work. This is why the musical figure is placed at the beginning of the overture.

This interpretation of the three-note motif is possible only after carefully listening to the entire record multiple times. The written text that accompanies the beginning of the piece, bearing the words “tre note/tre note sole mi bastano” (three pitches/three pitches alone are enough for me), brings the viewers’ attention to the opening line written by Schipa and fills the notes that follow with meaning, tying them inextricably to the figure of Euridice. If in a strictly musical sense the three-note arpeggio cannot legitimately be called a motif, the images change its status by empowering it with an explicit dramaturgical mission. In the first few minutes of the film, the insistence of the camera on these pitches, written both as and musical notation, communicates to the viewer the importance that these pitches will assume in a way that music alone cannot express. The soundtrack alone cannot convey their unique value, at least not at so early a point in the film. The images visually confirm what we hear, taking on what Bisoni calls the function of visual accompaniment. [38] More importantly, they are an early example of how Schipa sought to inscribe the recorded album within a visually salient narrative, thus in a sense endorsing Marengo’s definition of the film as a “visualized soundtrack.”

“Eccotela qui” (Here she is) is the track that accompanies the scene in which Orfeo meets his beloved Euridice (Eva Axen) and sings of his love to her. [39] Compared to the opera’s other tracks, in “Eccotela qui” narrative time is suspended. This allows the protagonist to express his innermost feelings (as in a conventional operatic aria). The piece begins with a repeated guitar riff over which various people answer the question: What is happiness? As we hear their different answers, we see images of Orfeo intent on playing the guitar while Euridice enters a church. When she draws his attention, a cut takes the two of them to a place where Orfeo had awakened earlier. This place is now suffused with the atmosphere of a dream, however. The change in visual style and editing rhythm contributes to emphasize the meeting between the two lovers. A few, fast-paced shots show Schipa sitting at a desk reading a black volume marked “R. Tagore” (a book of poems by Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore). Orfeo looks at himself in a pool of water and sees his double with a “painted” face. Euridice smiles at him. A cutaway shot shows the Narrators in the recording studio, smiling at the young couple. Euridice caresses Orfeo’s head as he leans over the water and turns away. On the freeze-frame of the close-up of Orfeo’s expression as he sees Euridice, one of the Narrators (Marco Piacente) intones the first notes on the words “Eccotela qui, davanti agli occhi” (Here she is, before your eyes). Euridice pushes Orfeo’s head underwater.

After we have seen these images, Orfeo’s solo part begins. The shots that follow are not linked to the soundtrack, however, nor do they move the story forward. Instead, they are conceptual in nature and quite different from one another at that, their meaning buried. The shot of Schipa reading verses from Tagore in his study at home alternates with images of Orfeo unveiling a statue of Euridice with a triumphant gesture before a festive audience throwing hats in the air or those of waves crashing against the rocks. [40] This is not to say that the picture is entirely devoid of a logical order; some of the images are conceived with the musical progression in mind. For example, the shot of Orfeo and Euridice removing the mosaic tiles that conceal each other’s faces resonates with the musical phrasing. Schipa has stated that this type of synchronization was conceived in macchina (in the camera), that is, during filming. [41]

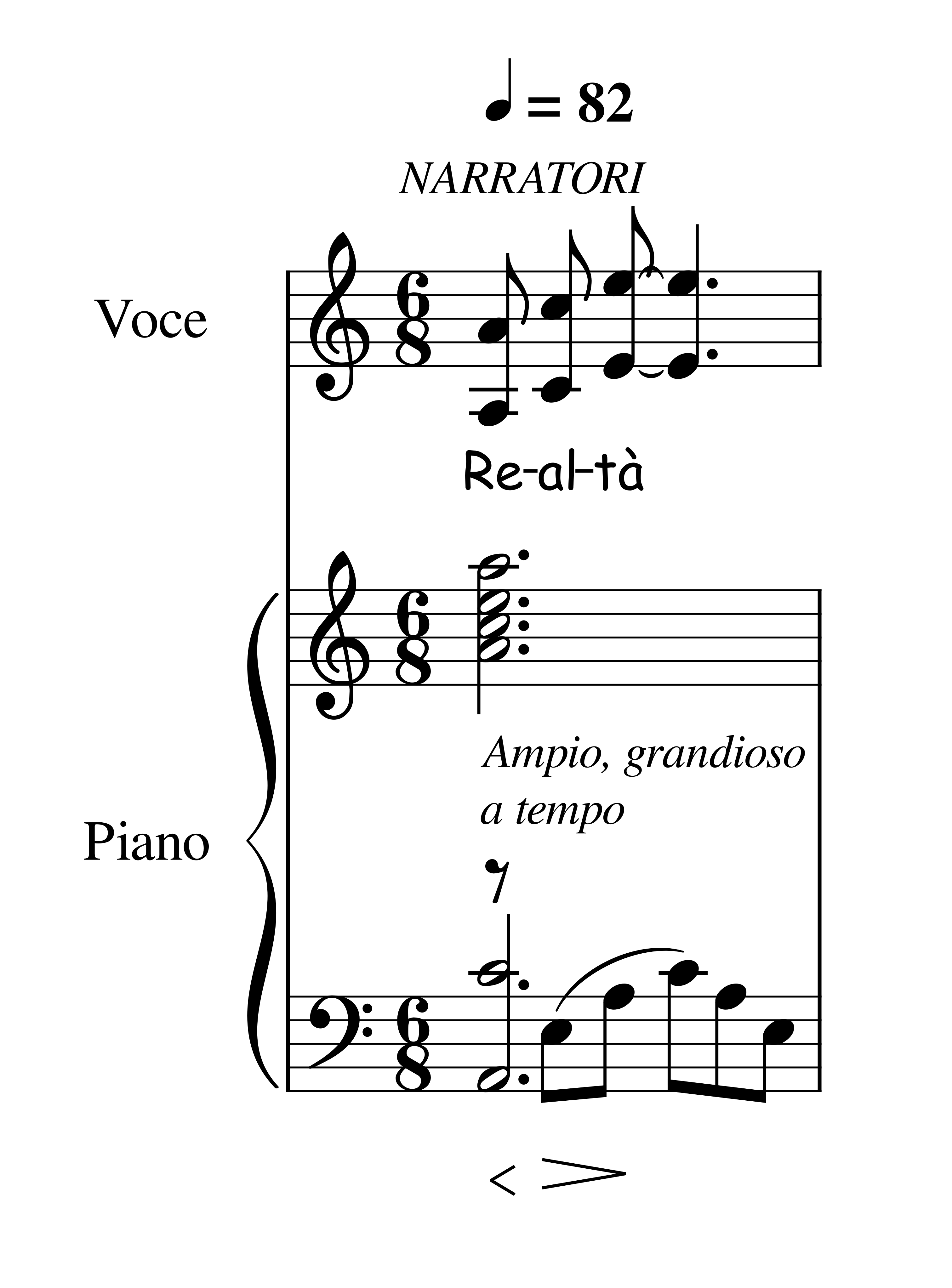

As seen in Figure 5, the “three pitch” fragment is at this point also reprised. After Orfeo declares his love for Euridice, the three Narrators sing an ascending arpeggio of A minor (the third note is tied to a longer one) on the word “re-al-tà” (reality), articulated in the shape of three syllables.

Fig. 5 – Excerpt from the track “Eccotela qui.”

An intervallic variation of the initial musical fragment helps develop the musical dramaturgy further. If in the opening the interval between the first two notes of the melodic cell is a minor second, which contributes to an aura of mystery, here it is a minor third. The change establishes a more soothing and perhaps even casual atmosphere. Due to the changing interval, the relationship between the two melodic cells may appear very weak. Yet one thing is certain: the music suggests Orfeo’s realization and as such it is a turning point in the narrative. Prior to the repetition of this variant of the “three-note” fragment, Orfeo sings of his love for Euridice, and then the melodic cell—in its altered form sung on the word “re-al-tà”—takes on the function of defining the feeling Orfeo could not name. But only the images clarify the relationship between the initial fragment and what I have now defined as its variant, as well as its meaning. The Narrators, who play a role akin to that of a Greek chorus, also sing these three pitches in the recording studio. This choice serves to emphasize the significance of this moment of the film. The passage clarifies that to Orfeo Euridice is the ultimate expression of the “real.” Schipa, in turn, views Orfeo’s love for Euridice as the reality that stands in opposition to the illusion of happiness sought in drugs.

At the end of the same piece, the three pitches (in the form presented in the overture) are echoed in Orfeo’s lines referring to Euridice: “Sei proprio come la musica/Senza di te non sarebbe più vita” (You are just like music/Without you there would be no more life). Euridice, then, is like music—that is, the vision of reality that Orpheus can play using only a few notes. The “three-pitch” fragment and its variation musically unite the character of Euridice with the concept of reality, which for Schipa represents the only thing one needs, because it is the truest of all. These three pitches and their various iterations, then, encapsulate the moral of the fable of Orpheus as interpreted by Schipa.

Schipa visualizes a song that is essentially static, without narrative development. How, then, does he manage to inscribe the passage in the filmic images? Tellingly, Schipa does not focus on the protagonist who, overwhelmed by passion, sings of his love for Euridice. As mentioned above, the singing is not synchronized with images of the performance. Indeed, the scene does not perform the function of visualizing the sound at all. Orfeo’s singing can be traced back to what Chion calls “internal sound”—that is, sound that expresses the protagonist’s thoughts and psychology in the scene. [42] The choice not to visually display Orfeo’s singing allows viewers to tune into the protagonist’s feelings, as we are the only ones who can hear his words of love. It is no coincidence that this piece is arranged for orchestra and does not include electric instruments or the rhythm section of the rock ensemble (only the drums are heard). Where in the opening scene Schipa decided to make the performance of the ensemble fully visible, here the instruments of the orchestra remain all but invisible. As Wollman has shown, in the traditional musical orchestral music does not need to be anchored in the film’s storyworld. Instead, it has the function of focusing the attention of the audience on the narration and enshrining the singing voices. [43] Chion locates such unanchored music in “an imaginary orchestra pit.” [44]

In “Eccotela qui,” then, images and music have different yet complementary functions. If Orfeo sings of his love for Euridice because he discovers that she is the representation of reality that leads to genuine happiness, the video component has the function of amplifying the dimension of the dream (more difficult to express through song). The images described above can be understood as echoes of Orfeo’s dream, each limited to a particular place. The image that closes the piece, significantly, shows Orpheus asleep with Euridice.

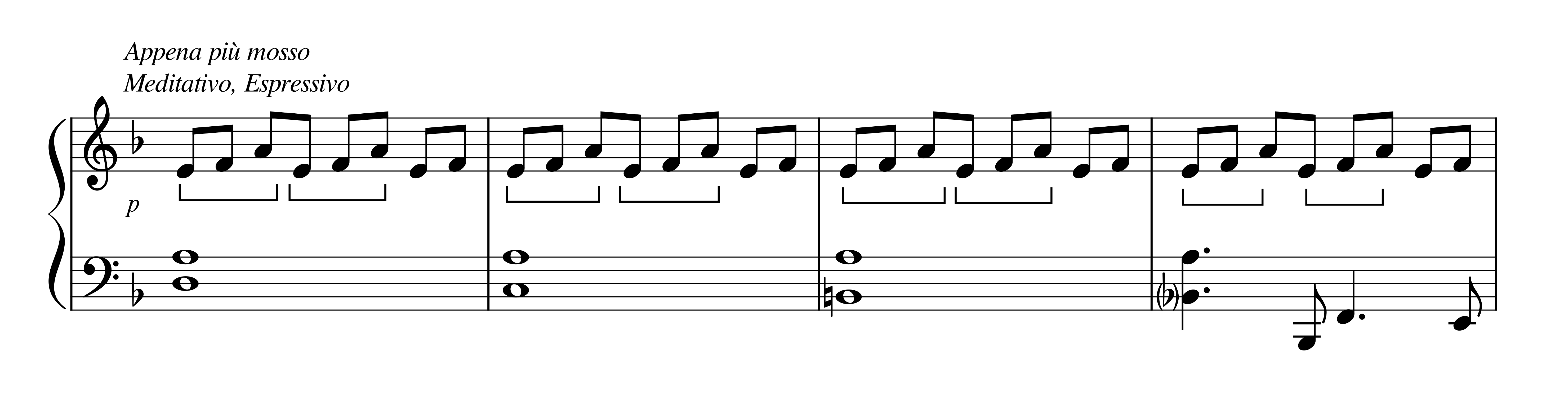

My next and last example features the arrival of the “Venditore di Felicità” (Happiness Vendor), played by a young Renato Zero. [45] He is a Luciferian figure, the personification of the serpent of classical mythology, a charlatan who sells Orfeo the illusion of happiness in the form of drugs and takes his bride Euridice in return. During the marriage ceremony between Orfeo and Euridice, the strings used to unite the two lovers morph into the triangular head of a serpent. The distorted sound of eerie laughter and the sepia-toned image of a serpent segue into the entrance of the Happiness Vendor. Accompanied by a syncopated, dotted rhythm entrusted to the rock ensemble, he enters the stage driving his house-shaped hawker’s booth, covered in children’s drawings and the misspelled word “felicittà,” (happiness, the second ‘t’ crossed out). This shady figure introduces himself to the commune of hippies from inside his smoky den, where he is brewing potions, as he sings his first line, “Sento dei canti dalla strada” (I hear chanting in the street). He is next seen fill a syringe over a pot in which liquid is boiling, grab Orfeo and (figuratively) inject drug into his body. A rapid montage shows the movement of the syringe crosscutting with the drops of liquid coming out of the needle. In a strange, distorted voice, the Venditore invites Orfeo to follow him.

Schipa has managed to link the track “Venditore di Felicità” to images that represent the Venditore’s complex and multi-faceted character. Céline Pruvost has observed that the Venditore is a polymorphous character, pointing out that Schipa calls upon references and aesthetic models from various artistic practices such as music, cinema, and painting to associate this shadowy figure to that of the devil. [46] The Venditore is presented through what I like to call a “montage of attractions” in which the alternation of seemingly disparate images produces new meanings. [47] At the beginning of the scene, the image of a serpent is juxtaposed to that of the Venditore’s entrance to suggest to that the character is evil. Throughout the piece, shots of the entrance scene are alternated with stock footage of snakes chasing fleeing mice. As the Venditore grabs Orfeo and the latter’s face morphs into a mask, we see for a split second the image of a predator assaulting a small prey. It is a significant, albeit fleeting, sync point, an audio and video “synchresis” (to quote Chion), in which the rapid montage of these images, accompanied by a dry drum roll and emphasized by the subsequent sudden stop of the musical accompaniment, underscore the meaning of the action. [48] Orpheus has fallen into the trap of the Mephistophelean Venditore, and he will not be able to escape. Once again, the images flesh out what the music alone, drum roll notwithstanding, could only suggest.

Spectators familiar with the myth will understand that the Venditore is the personification of the serpent that in the classical fable kills Eurydice. In the Western tradition, the image of the serpent has always been associated with the diabolical and evil in any case. Pruvost has pointed out that the Venditore entices Orpheus by offering him a happier life, recalling the serpent’s biblical role as tempter. This allusion is emphasized by the makeup on Renato Zero’s face, which resembles the scales of a reptile. [49] Pruvost also highlights how the character’s tall, dark silhouette and the contrived atmosphere created by the shadows in his den, as well as the use of smoke, rework in a vernacular context the aesthetics of expressionist cinema—particularly Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920). These elements return each time the Venditore appears on stage, thereby embodying “the principle of the musical theme in the language of cinema.” [50]

Fig. 6 – Still frames from the scene “Venditore di Felicità.”

Pruvost also emphasizes how the complex construction of the track is decoupled from the traditional notion of the song form. [51] The sung part is built around the libretto, and—particularly in the second section of the piece—the music supports the exchanges between the two protagonists. The track consists of a first stanza, repeated twice, in which the singing has a marked melodic character. The second section, in which the musical accompaniment is almost absent, is a dialogue between the Venditore and Orfeo in the form of a recitative that occasionally also leaves room for spoken lines. The text alone, without music or imagery, amounts to no more than the call of a street merchant who traffics in happiness for the good of the people he encounters. It is the music and especially the accompanying images that make the character devilish and disturbing. Absent the screen dramatization, listeners cannot imagine Orfeo being physically trapped and, beguiled by the Venditore’s words, accepting a dose of drugs.

The melodic line sung by Zero has a strongly undulatory contour. After the attack with a minor seventh leap on the first two syllables, the melody descends and then rises again.

Fig. 7 – Excerpt from the track “Venditore di Felicità.”

The cyclic, serpentine rise and fall of this melodic line create a dreamlike atmosphere: an ambience of mystery and tension. The corresponding image is the needle of the syringe with a few drops of liquid rising upwards, against gravity. The image enshrines the moment—the point of no return—at which the Venditore injects Orfeo with the dose of drugs that will lead him to lose Euridice. The background effects and distorted sound of Zero’s voice, redolent of the hissing of a snake, complete the construction of the character. The lyrics align with this sonority. Words begin with or contain phonemes such as the incorrectly-defined “‘s’ sorda” (literally, the “deaf” /s/, which in English is referred to as “voiceless”), /f/, and /t/. These include “felicità” (happiness), “specialità” (specialty), “raffinato” (refined), “affidato” (entrusted), and “fratellino” (little brother). The predilection for these sounds phonetically emphasizes the association between the Venditore and a metaphorical serpent. The recurring tritone and the use of diminished and semi-diminished chords, moreover, create strong harmonic tension. In the opening verse, the first syllable of the word “servirà” (will serve) is underpinned by a chord containing a tritone interval that is emphasized by the voiceless /s/ and the accenting of the corresponding syllable. This use of harmonic and melodic elements helps to increase the sense of anguish and to musically characterize the Venditore as diabolical. [52]

Fig. 8 – Excerpt from the track “Venditore di Felicità.”

The images build a more detailed framework of references through precise, calculated editing, rhetorically effective sync points, and visual choices that call to mind a wide range of cultural and artistic models. This piece is an important example of Schipa’s concept of music as an act of direction—as a tool, that is, both for constructing a drama and developing a narrative. Not only are the musical tempos written with the corresponding images or camera movements already in mind, but much of “Venditore di Felicità” is also composed of dialogue that was written with the explicit intent to be visualized. Schipa sought to make the music serve a poetic idea, and consequently, the development of the narrative of the opera.

Orfeo 9 , from record to film musical

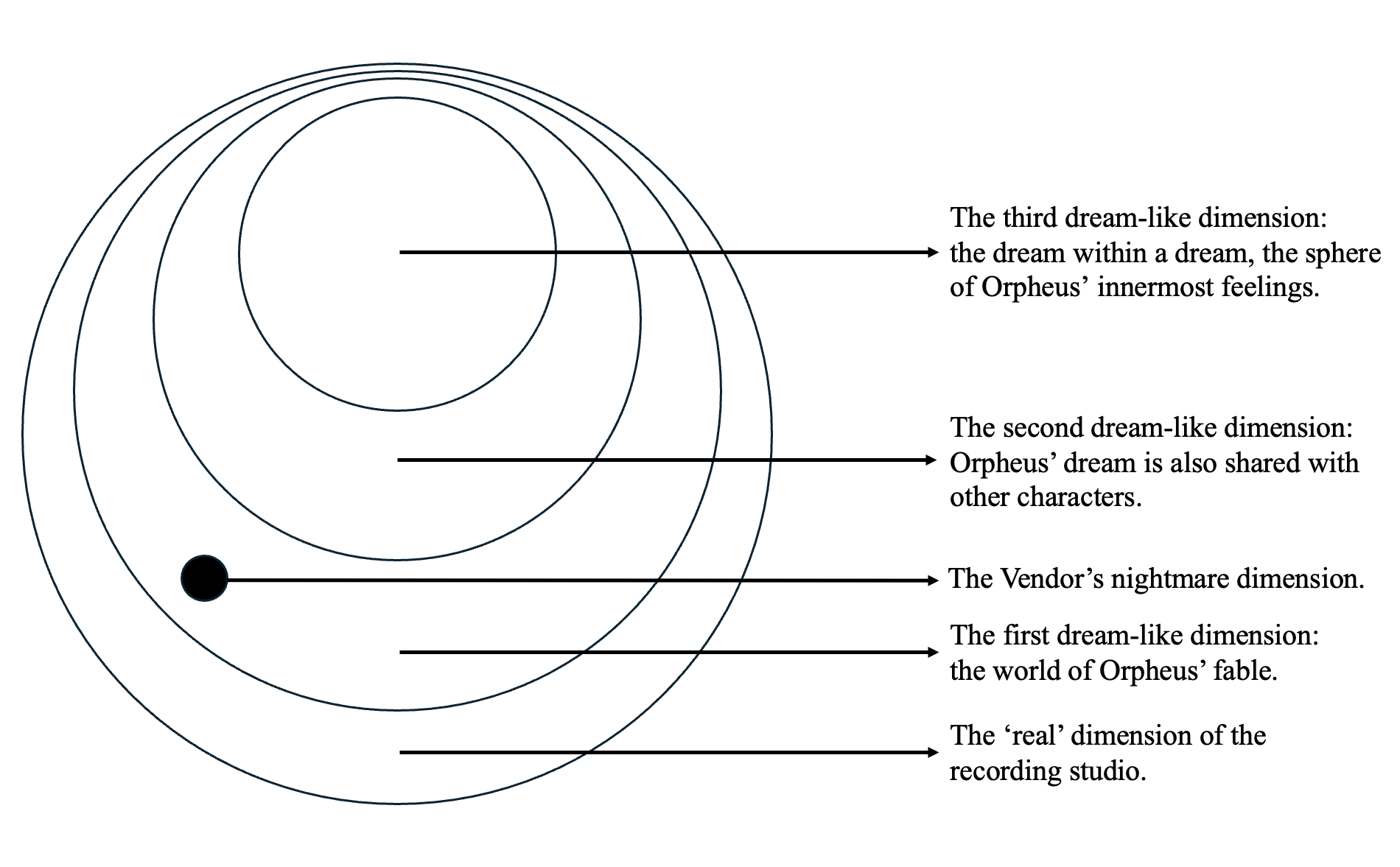

The narrative structure of the film consists of several concentric levels activated by the recording session on which the narrative hangs.

Fig. 9 – Structural diagram of the concentric spheres that constitute the plot of Orfeo 9.

The first and outermost level is that of the recording room where Schipa, the three Narrators, and the musical ensemble play and sing the opera. This is constructed as an artifice—that is, a projection of the musical performance. During the film, the camera returns to frame the recording studio and the movements of the musicians, focusing especially on the comments of the Narrators. The meta-filmic level is, as Miceli has argued, the place “where cinematographic language is extolled as the true magic and extreme epiphany of artifice.” [53] Indeed, this level highlights the ways in which the subsequent dream-like spheres are tied to the imagination and to dreams. Not coincidentally, the viewer is invited to enter the world of the fable at night, just before sunrise.

This construction has much in common with what Sergio Miceli calls “the Kelly model”—that is, the filmic formula associated with the actor/dancer Gene Kelly and based on a series of ideal spheres, like “a dream within a dream within a dream”—each sphere folded within the next. Similarly, the rather thin plot of Orfeo 9 is demarcated by the protagonist’s continuous entrances and exits from dream-like spheres—the underpinning of which is, as we have seen, the recording studio. The film is an example of an integrated musical in which the musical number is not merely embedded in the narrative but also overcomes its status as fiction. The integration of musical numbers into the narrative is made possible thanks to the world of the fable which, as conceived by Schipa, is an imaginary dimension capable of evoking other dream spheres. In Orfeo 9, everything is a dream, and within that dream, anything is possible.

This model lends itself to Schipa’s reworking of modern myth because, as Miceli states, “the [Kelly] formula can facilitate at once realism and allegory, everydayness and abstraction, predictability and surprise.” [54] Accordingly, Orfeo 9 attempts to blend opposing registers. For example, the avowedly constructed film studio scene of Orfeo and the Vivandiere immersed in a dreamlike environment as they discuss the explosion of the A-Bomb is followed by shots of the protagonist amid the traffic of contemporaneous Rome. Each scene is thus placed in a different dream dimension, and the audience is able to connect even the most divergent scenes so that they can coexist in something like an ordered whole. Some images draw on the aesthetics of rockumentary, others gesture toward the industrial film of those years via quotations of the trilogy of Orphic films by the poet and director Jean Cocteau. Different film genres coexist and with them, what Simone Arcagni has defined, different modes of “musical re-writing of the image.” [55] Such an eclectic display of registers, styles and modes of spectatorial address pulls Orfeo 9 away from the realm of the musical. Conversely, it suggests that the musical is best understood as a mode of representation rather than a genre in the strict sense.

In my commentary on three exemplary moments of Orfeo 9, I have focused on the ways in which a double LP may be remediated on film within the parameters of the musical. Orfeo 9 draws attention to the potential of the musical understood as a mode of representation—a characteristic that, as Rick Altman has argued, defined the early musical [56] —in that it encompasses a wide range of cinematic genres exhibiting divergent aesthetics. This is not only because the film musical has very regular tempos and rhythms, as Massimo Locatelli points out, [57] but also because it contains other worlds within itself.

I have explored what the language of one medium can offer to the other or, more precisely, how cinema can flesh out a soundtrack composed to be visualized to begin with. Pop opera thus stands as an example of how the study of the genre of the musical in Italy can—indeed, should—extend its reach to embrace a cross-media, and cross-format, understanding of popular music. I have demonstrated how the listener of the recording and the television audience enjoyed two completely different experiences. Through images, Schipa creates a place for the myth of Orpheus from within the musical, seeking in the genre a synthesis between different modes of remediation recorded tracks to rework a modern myth. Playing with the possibilities offered by his formal models, Schipa uses visual aesthetics from other film genres, constructing a polymorphic version of the myth while maintaining the essence of the fable of Orpheus.

* This article is a new and expanded version of earlier papers presented in past years at various conferences. One of these papers was recently published in the proceedings of the conference Le ricerche degli AlumniLevi, organized by Fondazione Ugo e Olga Levi (Venice, 14–15 October 2022). See Daniele Peraro, “Una «colonna sonora visualizzata» per un mito moderno: Orfeo 9 di Tito Schipa Jr.” in Le ricerche degli AlumniLevi: la giovane musicologia tra riflessioni, dibattiti e prospettive, ed. Paolo De Mattei and Armando Ianniello (Venice: Edizioni Fondazione Levi, 2024): 145–56.

[1] The title is in this respect a statement. Schipa’s choice to juxtapose the number “9” to the name of the mythological cantor is a homage to the Beatles’ song “Revolution No. 9” (1968). A poster of the song is seen hanging in the recording studio in the title sequence. “Revolution No. 9” is a synthesis of rock and musique concrète aimed at expanding the boundaries of the song form. In a similar vein, Schipa tried to combine the sounds of the rock genre with Italian melodrama to build a new type of rock musical. See Tito Schipa Jr., Orfeo 9 – Then an Alley. Nella storia di due spettacoli musicali, una via alla rifondazione italiana dell’opera popolare (Lecce: Argo, 2017), 64.

[2] See the scene “Venditore di Felicità” (Happiness Vendor) examined below. See also, Schipa, 174.

[3] Tito Schipa Jr., personal communication, December 22, 2022.

[4] “Cominciavo ad intravedere che l’idea di tramutare Orfeo 9 in film, restava allettante, certo, ma che in realtà bisognava cambiare i fattori dell’operazione: non avrebbe dovuto trattarsi di un film con quella colonna sonora, ma di quella colonna sonora da cui trarre un film . Immagini suggerite dalla musica, insomma, e non l’inverso.” Schipa, Orfeo 9 – Then an Alley, 121.

[5] Schipa Jr., 121.

[6] Tito Schipa Jr., personal communication, December 22, 2022.

[7] Tito Schipa Jr., Sono Passati I Giorni / Combat, Fonit SPF 31290, 1971, 7’’. See Schipa, Orfeo 9 – Then an Alley, 120–2.

[8] This is why the film and the record are of almost equal duration, about 82 minutes in total.

[9] “L’accoppiamento immagini–suoni è uno dei pregi maggiori di Orfeo 9 . In sostanza è il primo esperimento italiano di colonna sonora visualizzata; e non è poco se si considera che normalmente un film viene prima scritto, interpretato, girato e poi vi si aggiunge una colonna sonora; qui è stato fatto il lavoro inverso: su di una colonna sonora sono state sovrapposte delle immagini.” Renato Marengo, “Pop in Tv: il mito di Orfeo,” Ciao 2001 5, no. 47 (1973): 62.

[10] Schipa, Orfeo 9 – Then an Alley, 142.

[11] Claudio Bisoni, Cinema, sorrisi e canzoni. Il film musicale italiano degli anni Sessanta (Soveria Mannelli: Rubbettino, 2020), 10.

[12] Raymond Knapp, “Performance, Authenticity, and the Reflexive Idealism of the American Musical,” in Identities and Audiences in the Musical: An Oxford Handbook of the American Musical, ed. Raymond Knapp, Mitchell Morris and Stacy Wolf, vol. 3 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 209.

[13] Knapp, 218.

[14] Jake Johnson, Masi Asare, Amy Coddington, Daniel Goldmark, Raymond Knapp, Oliver Wang, and Elizabeth Wollman, “Divided by a Common Language: Musical Theater and Popular Music Studies,” Journal of Popular Music Studies 31, no. 4 (2019): 32.

[15] K. J. Donnelly, “Visualizing Live Albums: Progressive Rock and the British Concert Film in the 1970s,” in The Music Documentary: Acid Rock to Electropop, ed. Robert Edgar, Kirsty Fairclough-Isaacs, and Benjamin Halligan, (New York: Routledge, 2013), 171.

[16] George Reddick, “The Evolution of the Original Cast Album,” in Media and Performance in the Musical: An Oxford Handbook of the American Musical, Volume 2, ed. Raymond Knapp, Mitchell Morris, and Stacy Wolf (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 114.

[17] See Kenneth Womack and Todd F. Davis, Reading the Beatles: Cultural Studies, Literary Criticism, and the Fab Four (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2006), 16.

[18] See George Reddick, “The Evolution of the Original Cast Album,” 114. See also Elizabeth Lara Wollman, The Theater Will Rock: A History of the Rock Musical, from Hair to Hedwig (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006), 90–102.

[19] Julie Hubbert, “The Compilation Soundtrack from the 1960s to the Present,” in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies, ed. David Neumeyer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 299.

[20] Wollman, The Theater Will Rock, 90.

[21] Schipa, Orfeo 9 – Then an Alley, 147.

[22] Roy Shuker, Popular Music: The Key Concepts (London: Routledge, 1998), 5.

[23] John Rockwell, “Rock opera,” in Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online , 2002.

[24] The stage musical of The Who’s Tommy premiered on Broadway in 1993. See Wollman, The Theater Will Rock, 159–170.

[25] In 1970s Italy, rock and progressive rock music was defined by the press and by the bands themselves as “Italian pop.” As Jacopo Tomatis points out, music festivals that hosted groups defined today as progessive were named “Festival pop.” Nowadays, however, pop is a very generic term, so I have chosen to use rock for clarity of exposition; see Jacopo Tomatis, Storia culturale della canzone italiana (Milano: Il Saggiatore, 2019), 400–8.

[26] For a history of the concept album and the opera rock, in particular in Italy, see Daniele Follero and Donato Zoppo, Opera Rock. La storia del concept album (Milano: Hoepli, 2018).

[27] The entire film, in color and restored in high quality, is available on Orfeo 9’s official YouTube channel. The scene analyzed here starts at 0:00:32 of “ORFEO 9 di Tito Schipa Jr. (1972),” Orfeo 9 Ufficiale, uploaded on January 31, 2022.

[28] Scholars who discuss the diegetic/non-diegetic opposition in film musicals include Rick Altman, The American Film Musical (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), 62–7; Raymond Knapp, The American Musical and the Performance of Personal Identity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006), 67–8; Graham Wood, “Why Do They Start to Sing and Dance All of a Sudden? Examining the Film Musical,” in The Cambridge Companion to the Musical , 2nd ed., ed. William A. Everett and Paul R. Laird (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 316–18; Nina Penner, “Rethinking the Diegetic/Nondiegetic Distinction in the Film Musical,” Music and the Moving Image 10, no. 3 (2017): 3–20. Scott McMillin illustrates the difference between diegetic songs and out-of-the-blue numbers in stage musicals: see Scott McMillin, The Musical as Drama (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006), 112–16.

[29] Altman, The American Film Musical, 65; Jane Feuer, The Hollywood Musical , 2nd ed. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993), 68–76.

[30] Bisoni, Cinema, sorrisi e canzoni, 149.

[31] Paul Sanden, Liveness in Modern Music: Musicians, Technology, and the Perception of Performance (New York: Routledge, 2013), 11.

[32] See Simon Frith, Performing Rites: On the Value of Popular Music (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998), 224–25.

[33] See Alessandro Bratus and Maurizio Corbella, “This Must Be the Stage: Staging Popular Music Performance in Italian Media Practices around ’68,” Cinéma & Cie 19, no. 31 (Fall 2018): 36–7.

[34] This statement was made by Tito Schipa Jr. during a conversation with Daniele Peraro and Alessandro Avallone as part of the live-streamed event Alumni Levi Live. See “Alumni Levi Live, Musica e Mito, 9 novembre 2022,” Fondazione Ugo e Olga Levi, streamed live on November 9, 2022.

[35] Elizabeth Lara Wollman, The Theater Will Rock, 32.

[36] Schipa, Orfeo 9 – Then an Alley, 175.

[37] I use the term “musical motif” as it is defined by Sergio Miceli: “a short succession of sounds with either a complete or incomplete melodic character, but which—unlike the theme—is not subdividable.”; see Sergio Miceli, Musica per film. Storia, estetica, analisi, tipologie (Lucca: LIM, 2009), 611.

[38] Bisoni, Cinema, sorrisi e canzoni, 149.

[39] “Eccotela qui” begins at 0:26:33 in “ORFEO 9 di Tito Schipa Jr. (1972).”

[40] The frame that shows Schipa reading poetry in his study also shows the poster for Then an Alley (1967)—a previous work with beat music written and performed by Schipa—hanging on the wall. This reference is not casual: the author cites himself and his previous work, which paved the way for the idea of the theatrical version of Orfeo 9.

[41] Schipa, Orfeo 9 – Then an Alley, 165.

[42] Michel Chion, Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen, trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 76.

[43] Wollman, The Theater Will Rock, 207.

[44] Chion, Audio-Vision, 68.

[45] “Venditore di Felicità” begins at 0:34:38 in “ORFEO 9 di Tito Schipa Jr. (1972).”

[46] Céline Pruvost, “Orfeo 9, de Tito Schipa Jr.: une réécriture polymorphe du mythe,” Cahiers d’études romanes, no. 27 (2013): 259–79. Although her focus is limited to this scene, Pruvost is one of the few scholars to have examined Schipa’s opera in detail.

[47] Pruvost,paragraph 34.

[48] As Chion explains: “ Synchresis (a word I have forged by combining synchronism and synthesis) is the spontaneous and irresistible weld produced between a particular auditory phenomenon and visual phenomenon when they occur at the same time;” Chion, Audio-Vision, 63.

[49] Pruvost, “Orfeo 9,” paragraph 34.

[50] Pruvost likely refers to the logic of the recurring motif in theatre and opera. Pruvost, “Orfeo 9,” paragraph 33.

[51] Pruvost, paragraph 30.

[52] Pruvost, paragraph 31.

[53] Miceli, Musica per film, 767.

[54] Miceli, 757.

[55] Simone Arcagni, Dopo Carosello. Il musical cinematografico italiano (Alessandria: Falsopiano, 2006), 207.

[56] Altman states that, in the first sound film, musical numbers were “a manner of presenting narrative materials that already had its own generic affinities.” Rick Altman, Film/Genre (London: British Film Institute, 1999), 31–2.

[57] Building on the most recent studies on the psychology of rhythm and tempo in music, Locatelli analyzes the film musical as a product consisting of a succession of musical numbers, thus bringing this film genre closer to the song compilation practices in popular music records. Massimo Locatelli, “Il catalogo musicale pop e il cinema delle emozioni. Il caso Yuppi Du (1975),” Schermi 4, no. 7 (2020): 65–6.