ARTICLE

Resonance *

Caroline A. Jones

Sound Stage Screen, Vol. 4, Issue 2 (Fall 2024), pp. 17–38, ISSN 2784-8949. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. © 2025 Caroline A. Jones. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54103/sss28731.

Although the origins of the word resonance attach the concept to sound—“the reinforcement of sound by reflection or by the synchronous vibration of a surrounding space or a neighboring object”[1]—a wider definition needs to embrace any vibrational movement that unfolds over time in a body, in sympathetic response to vibratory stimulus from outside it. Resonance as sympathetic vibration is often felt before it is heard. [2] Sympathetic vibration is the phrase that already references this feeling: Sym[with]+Pathos[feeling] = feeling-with-vibration. This essay takes up the “feeling-with” relation to resonance and its co-vibrational energies. Building on much existing scholarship (Christoph Cox, Veit Erlmann, Nina Eidsheim, Salomé Voegelin, and artists such as Pauline Oliveros, Christine Sun Kim, Alvin Lucier, and Jana Winderen), I want to offer a resonance that expands beyond the ear. More than “reduced listening” or insistence on immediate “affect,” this essay recommends an expanded embrace of feeling, distributed across and beyond a body, experienced over time and in intellection with others on the planet. [3] Thought fully, resonance pushes away from the audist insistence on mechanical and mathematical causality in a floriated Ear toward entangled, temporally con-founding, conceptually rigorous, embodied and potentially multi-species co-presence.

Resonance has become a desirable theoretical tool in recent years, showing up in philosophy and sociology as well as sound studies. [4] But if I begin by sharing the enthusiasm for the sympathy of shared vibrations, I note for the reader: in this essay, resonance is not always kind. Resonance opens onto multiple possibilities: vibratory phenomena can arise as disturbance as much as harmony. Unsettling and unfixing the boundaries of a self, resonance can arise via situated experiences of artworks that vibrate bodies and organs, yielding the potential for humans to recognize that they are vibrant matter in concert with the planet. [5]

In speculating on how an infant human emerges into consciousness, William James deployed the active acoustic metaphor of a buzzing confusion: multiplied resonant vibrations colliding in a newly-sensing body. Buzzing is difficult to isolate as purely auditory; it has haptic qualia. It also invokes richly sonic possible worlds, [6] suggestive of the densities of arthropod swarming. More-than-human species fuse buzzing sounds with the buzzing look of wings in motion—as in the waggle dance of bees. In these social insects, buzzing is aligned with bodily orientation, temporal sequencing, and the vibrations given to the hive by other bees’ vigorous movements. Taken up mimetically by community members, specific instances of the waggle dance communicate precise information about the best site for the future hivemind. [7] Yet in contrast to the bees’ developing certainty, James’s buzzing “confusion” signifies both something hard to figure out and an overlapping coming-togetherness (con-fusion) in the infant, whose synapses are exploding with connections that must later be “pruned” (for language, anti-synaesthetic sensory organization, and appropriate social exchange). For James, this process eventually condenses, concertizes, and clarifies the resonant “buzzing” into a meaning-making-mind.

Between the bee dance and the bewildered infant, harboring uncertainty about whether resonance must be “resolved” into a message might be what sound art is good for. Encountering a work of art aimed to resonate us may open up the settled auditor to the sonic possible worlds James evokes, of “blooming” (as well as buzzing) confusion. Composer Pauline Oliveros taps metaphors of resonant co-creation and co-presence in her sonic meditation Teach Yourself to Fly (1970). Teach Yourself to Fly names its transcendence of a listening ear, imagining whole bodies floating weightless in the air, propelled by the shared vibrations of participant-listeners-resonators holding single tones whose amplitude and pitch are unspecified but interwoven. Hums behind closed lips, open mouths that “vocalize,” air pushed through reeds, tones from resinous catgut slowly dragged across twined strings of sheep intestine, nylon, and steel—these are all permitted sources of vibration within the piece, which can also be as simple as a circle of humans with no instruments other than their own bodies’ breath, vocal cords, and watery viscera. Closed eyes intensify the experience, as tapestries of tones mingle in ears and envelop the body, moving through its various tissues. Yes, we can hear it, but Fly also produces a veritable organology for participating humans: vibrating larynges, but also cavities in the head, sinuses, kidneys, bladders, lungs, bones—each internal “instrument” resonating within its own highly variable materiality and resonant wavelengths. The score tells us that to perform this piece, we must “always be an observer” and also “gradually introduce [our] voice.” To “hear” this composition by Oliveros, you must be both attending and vocalizing. There is no distinction between “audience” and “performer,” a gift of the art world’s unfixity. Both categories dissolve, becoming interfaces with frequencies of audible and inaudible percussive waves that hoist us into the cloud of proximate participant sound. To fuse attending and vibrating actions is to acknowledge the mingled sensation of resonance, here in joyful ascent.

Fig. 1 – Pauline Oliveros and the ♀ Ensemble performing Teach Yourself to Fly in Rancho Santa Fe, CA (1970). Foreground to the left around: Lin Barron, cello, Lynn Lonidier, cello, Pauline Oliveros, accordion, Joan George, bass clarinet; center seated foreground to the left around voices: Chris Voigt, Shirley Wong, Bonnie Barnett and Betty Wong © Pauline Oliveros Papers. MSS 102. Mandeville Special Collections Library, University of California, San Diego.

Fig. 2 – The score as published in Pauline Oliveros, Sonic Meditations (Sharon: Smith Publications, 1971).

If and when “resonance” is summoned into human conversations about sound, it can work to hone alternatives to meaning-laden “listening” (a word absent from the score for Teach Yourself to Fly). As in Oliveros’s meditations on the sonic, the metaphorics of resonance carve new sensory possibilities out of co-presence and vibrating matter. The word “sound” already anticipates the epistemic capture that is called “listening” or “hearing.” Yet sound is only one means by which matter vibrates and hence resonates us. Of course, sound is a highly prized “signal” in an evolutionary game of taking information from a rustling, crackling, roaring, singing, stridulating multi-species planet—but there are other vibrations that penetrate and resound in bodies that move and are moved, in motion with/through/against the pulse of waveforms that circulate on a dynamic, watery Earth.

Resonance begins in Western philosophies with Pythagoras’s discordant hammer; [8] it becomes applied science with the rigorous “speech chain” causalities of physiology. [9] In between those histories, an empiricist such as Hermann von Helmholtz will want resonance to be quantifiable, a genealogy that still governs an entire branch of neuroscience and the physics of ion oscillations, in which resonance can be mathematicized as Fourier transforms. Scientists in modernity want to stabilize physiological phenomena; artists summon resonance to derange such certainty. Are my sensed vibrations in Fly from me, or all of us? As I learn to fly, that levity comes in a cloud of co-presence to the bodies and organs buzzing together.

A capacious bucket for vibratory phenomena, resonance throbs us—and cultural, scientific, and artistic approaches to this concept sharpen general queries about how (or whether) we can be certain about what we think we know of the world outside our ears. As I will argue more expansively below, attending to resonance is one way of becoming uniquely tuned to a more-than-human planet in which life envelops and sustains us, in entangled and intradependent ways. According to Veit Erlmann, acoustic and philosophical ways of thinking about resonance open us to different ways of listening, being, and reasoning in a world of oscillating matter. As Erlmann chronicled in Reason and Resonance, [10] the body’s sensory equipage (eye and ear, but also soul and viscera) was understood to be capable of resonance-as-sympathetic vibration; Erlmann follows scientists who sleuth out fibers and membranes and bony tubes inside the human ear to find physical “reason” and mathematical relations in auditory capacities to vibrate sympathetically to music and sound. What are consonance and dissonance? Do these have physical correlates in an outer, middle, and inner ear that unite to bridge the mysterious divide between inside sensations and outside phenomena? Do these organs behave with the self-logic of that beauty, mathematics? The age of Helmholtz and James determined how the resonating subject would be understood as an anatomical collection of strings and fibers, hammers and drums, rods and cones—all of which enact the epistemology of little machines, oscillating with various energies coming from the world to form aesthetic relations called harmony with resonating matter. Helmholtz, for example, dominated the discourse about resonance for decades, by making measurable science and numbers from the resonant tones that air made, moving rapidly across small openings in otherwise closed vessels: what some English-speakers call wind throb.

The vernacular phrase “wind throb” gives us a rather different figure to conjure with, an alternative to numeric fixity. In contrast to “5” or “12,” we have a vessel helplessly throbbing (viscerally or materially) with dynamic planetary atmospheres that entrain that body in a rhythm shaped by its form but not of its own making. By comparison, Helmholtzian science would obsess over bony and fibrous matter at microscopic scales, looking for physical guarantors of mathematical relations that would make reason out of resonance. Exploring the resonant phenomena perceived by humans, the mid-nineteenth-century German empiricist was determined to demonstrate his “piano key” theory of hearing—perceived sound was likened to the trichromacy of human vision, explained as a series of mechanical triggers yielding invariant pitch perception in dedicated structures of the ear. Causal steps in the Helmholtzian view: percussive forces are transferred from air into ear, eventually hitting cochlear “keys” in the organ of Corti to activate a single nerve fiber for each sensation of tone. [11] This yielded a piano-string analogy.

Figg. 3 and 4 – These particular tarnished Helmholtz resonators were imported to Boston, where they were visited by a young Canadian, Alexander Graham Bell, sent down by his father to experience the acoustic instruments in the MIT Physics collection. They are now housed in the MIT Museum, Cambridge Massachusetts USA.

To tame further the mysteries of resonance the experimentalist made purpose-built Helmholtz resonators: tuned vessels (first glass, then brass) allowing composite tones to be separated into precise resonant frequencies, each belonging to the diminishing or increasing size of its container, the set arranged in pre-determined mathematical relations. These adorable collections of hand-sized burnished orbs quickly evolved, from bespoke furnishings in Helmholtz’s private laboratory to hundreds of kits branded under his name. Sold to the teachers and universities that could afford them, they aimed to enlighten physics and psychology students. [12] The first of the resonators had been manufactured to Helmholtz’s specifications by Rudolph Koenig of Paris, their tapering “necks” placed gently in the ear to allow humans to hear sympathetic vibrations of the partial tones in a given sound source. Not surprisingly, the piano key, depressed and string sonified, would be not only the ready analogy for cochlear tone recognition, but the tone generator of choice for these resonant vessels (blow across a soda bottle for a cheap equivalent of the effect, truly summoned as some throbbing wind).

Doubtless, the words we devise to talk about music, sound, partial tones, resonance, sonic oscillations and throbbing vibrations are frustratingly inadequate. Does the word “timbre” capture what it is that my ears do when I distinguish a voiced flute from a factory whistle?—these objets sonores may have identical frequencies, but once compressed in an MP3 format and further altered by electromagnetic interference scrambling my kitchen radio and clipping off a tone’s attack, they can be challenging to distinguish. Far from a clean Fourier sine wave, timbre seems to be a function of the attack and diminution of a tone, not its pitch. From the medieval Greek τύμπανον —used for virtually all instruments except, ironically, the drum—“timbre” is the kind of blurred-edge concept characteristic of resonances of all kinds. Frequency cannot even control middle C—and that imprecision might then yield a metaphorical C, if you accept that a conceptualized pitch will actually vary from continent to continent, orchestra to orchestra, and perhaps even ear to ear in actual wavelength. So, despite “resonance” being tamed as frequency, it continues to thrive as fuzzy sonic material, as well as metaphor, in cultural circulation.

Fuzzy and buzzy, resonance is rather more like James than Helmholtz. Unlike the German scientist’s obsession with separating tones into their partials (captured in those handy vibratory orbs), James’s pragmatism was holistic. Perhaps this can be a general contrast drawn between two branches of Naturphilosophie, one half splitting into mechanistic physiology, and the other yielding an emergent domain of psychology. James (and John Dewey after him) held meaning to emerge as a matter of experience rather than physico-mathematical relations.

Jamesian fuzzy logics would not be tolerated by later neuroscientists (the prefix “neuro” adopting that hard, physical, “nerve fiber” in order to link to physiologists’ mechanical claims). As late as 2014, acoustic neuroscience researchers framed “resonance” as a problem for hearing aid design: messy, unorganized, chaotic “noise” in the logocentric system. [13] For language-based consciousness to claim a kind of knowledge of the world, resonant phenomena (in such a neuroscientific instrumentalism) must be trammeled and channeled for signal-sending. Hearing aids and cochlear implants both want resonance designed out, via relays of gating, filtering, sorting, and signal processing—fostering the goal of making a mental “identification” of the source and capturing linguistic meaning for strictly human business.

By contrast, for the differently-abled, the thrumming of resonance is rich with non-verbal information about the world. Both Georgina Kleege’s homage to her white cane as sonorous technology [14] and Alvin Lucier’s breakthrough sound work I am Sitting in a Room (1969) construct the resonant domain as a field of spatial relations, where the world surrounds and resonates us. Christine Sun Kim programs a bench with earphones that all who sit there can feel, but only some can hear (one week of lullabies for roux, 2018). This work stages resonance between hearing and deaf populations—if hearing divides, resonance unites the bodies in its field of thrumming oscillations. [15] Resonance offers the differently-vocal (Lucier’s stuttering) or the non-visual (Kleege’s Blind identity) or the anti-audist (Kim’s signing communities) a human enlargement of expertise based on “soundings” that understand the body as permeable to the world’s vibrations, attuned to its echoes, and untroubled by acousma. We do not need to identify the sound’s source to experience the field’s sonorous materialities.

This is explicitly not a neutral or universal resonance. Each body, being different and unique, will experience resonance uniquely, just as the “room tone” of Lucier’s composition will differ from space to space. Neither is the thrumming of resonance easily slotted as pre- or anti-cognitive (as in affect studies[16]). In recent years, scholarship has multiplied approaches to resonance through Queer sonorities or Indigenous resonant worlds. [17] Anti-essentialist, fully cultural resonance is what we want to theorize—but in the art, there may be an initial resonant encounter that sets theory aside for immanence (if only temporarily). Being with Oliveros’s Fly, or sitting with Sun Kim’s bench, allows a subsequent reflection on organology (the resonance within and among fleshy, watery parts) that can be disentangled from audition within a situated aesthetic experience. The claim being made here is that resonance is different from the signal-oriented science of hearing that technologies such as the “hearing aid” exist to exploit.

Expansive works of culture, sound art experiences foil the hearing aid’s necessary reductionism. Resonance is generously empirical rather than abstract. It tells us about various sources, all of them interesting. Like the sounds of water being poured into a vessel, vibrational information is richly multifaceted, telling some who pay attention that: the water is hot (or cold), the volume being poured is measly (or voluminous), the vessel is large (or small), it sits on the table (or the floor) inside a tiny room (or a vast chamber) and is near to hand (or out of reach from the listener). [18] This switch from “signal” to field is characteristic of resonant epistemologies—rather than reductive, they are enlarging. Rather than a compulsively consulted Cartesian interior, they are open to the always-entangled relations with a dynamic world.

Put differently, the gates and filters that the admirable Bell Labs collaborators Denes and Pinson first wrote about in the 1960s are only part of the story. Hammers, stirrups, tympani, and their quasi-mechanical “cussive” forces (percussion, discussion, concussion) are there, but thrumming unsettles mechanistic conceptions of these bits of bone and cartilage. “Feeling with vibration” goes beyond the bony; we might even give political agency to the sympathetic vibrational components of the assemblage as suggestively feminist: hairs, flesh, and fluids. [19] Even Erlmann, who has done so much to thicken the “cutere” of rhythm and pulse in resonance, charts the history of aurality as only within an ear, diagrammed only via the dry tissues flattened by anatomists and sliced for microscopy. In life, the human body is a sack of circulating fluids of one kind or another, membranes robustly organizing cells, spongy bags and glands, a meshwork of networked conduits to keep things moving.

Playing a constitutive role in the human reality of feeling-with sound, fluids contribute an essential step in how the watery mammalian body takes in vibrations; some will be experienced as “audible.” [20] Moreover, the privileged ear, divided neatly by anatomists into outer, middle, and inner has evolved to have as its most crucial final step an almost oceanic sogginess—the fleshy basilar membrane:

Outer ear: resonators conveying pressure waves from the world; pinna,

external auditory canal, and tympanic membrane (air);

Middle ear: impedance reduction via pressure amplification in ossicles (the

malleus, incus, and stapes), which aim their “cussives” through the cochlear

oval window (air);

Inner ear: frequency separation propagating to nerves; bony and membranous

labyrinth containing cochlea, semicircular canals, utricle, and saccule

(fluid). [21]

This flexible structure separates two fluid domains, and the “membranous labyrinth” filled with lymphatic fluids constitutes a whole that embraces a cochlea whose fluid-filled structures also make use of different densities in liquids and colloids—watery material crucial to wave propagation. Yes to bony bits, but double yes to the unctuous flows that entangle bodies with resounding sounds, securing, in cognition, an ongoing understanding of resonant phenomena.

Mammalian cousins, the cetaceans, returned to the oceans in evolutionary time; they use fluidic resonance in ways still mysterious to human marine biologists speculating about the “utility” of resonance in cetaceous society. [22] Resonance of fellow whales in these realms is deeply confused by human mining, oil extraction, shipping, and military action. Mysticete soundings of ocean depths and fathom-wide songs that can stretch over 24 hours (males are the singers, whether blue whales or humpbacks, but all mysticetes make social, community-connecting “calls”) remain as poorly understood as odontocete “acoustic fats” (thought to propagate and channel returning sonar clicks to their inner ears). What is resonance for in these ocean giants? Navigating, finding mates, locating food? Likely all of the above, in the largest creatures on earth who parse the chattering ocean as a fully vibrational realm of lively relations.

Art by humans is also a place to explore such aqueous resonance. Imagine for a moment lying back into an installation of Max Neuhaus’s Water Whistle (1971) in your neighborhood pool, ideally together with a congregation of water-slicked fellow participants. Neuhaus was a spokesman at the time for “avant-garde new music.” In Michael Blackwood’s documentary about the emergence of sound art, Neuhaus tells us about his interest in watery resonance as if it could constitute a new kind of instrument: “Many of the things that happen with wind instruments, with air, happen also with water, in water. I’m using water pressure to make sounds in water.” [23]

Figg. 5 and 6 – Max Neuhaus testing speakers in a pool for Water Whistle, first performed in 1971 at the NYC YMCA pool, with crowds enjoying the piece afterwards. Stills from New Music: Sounds and Voices from the Avant Garde New York, 1971 (2011) © Michael Blackwood.

This was one way of exiting music composition: “I got tired of intellectual music games. To me, music is a sensual experience, and I wanted to get into a situation where other things were happening.” The YMCA premier of Water Whistles in 1971 (as the title was pluralized by one Rolling Stone critic) was definitely a happening scene. Hoses were hooked up to cheap whistles, and as the water flowed into the pool in real-time the composer moved valves that altered water pressure and hence pitches, “sound focusers” were used to aim the resulting vibrations in different directions within the water volume for the 15-hour duration of the piece. For Neuhaus it was “a pool of music;” for the reviewer Jonathan Cott it was “trance-inducing, mantra-flowing composite sound through which you swam.” [24] What was the musical instrument here? The pool, its whistles, and the added water being pushed through them. Neuhaus celebrated the 6 inches of water that eventually overflowed the pool boundaries, a metaphor for how the composition enlarged the resonant properties of the space for submerged human bodies; the watery suffusion pulsed with continuous tones that interlaced, criss-crossed, and merged into a “resonating, slightly oscillating ten-note chord” [25] that many described as “dronelike” and pleasantly monotonous. [26]

Resonance usefully confounds the barriers we erect to separate a sonic outer world from an inner realm of quiet contemplation. “With your eyes closed,” wrote the Rolling Stone journalist chronicling Water Whistle, “it seemed as if the music, like some sleepy language, were inside your own head.” [27] It was, but also wasn’t. This is the useful con-fusion that resonance brings together: inside + outside + within + all-around.

Who’s to say whether or not the thumping and roaring that John Cage so famously describes at the heart of Silence (1961)[28]—experiencing the sounds of his cardiovascular and nervous systems while visiting Harvard’s anechoic chamber—do not also resonate outwards? Once Cage returned to social spaces, these hums might have linked him to others, now imagined as throbbing bodies experiencing the winds and heart-pumping stresses of a climate changed. Who’s to determine the limits of resonant oscillations in a field of relations? Joan Jonas insists on the way bodies can know other bodies in her new media work To Touch Sound (2024), offering a haptic title that imagines whalesong as a co-vibrational experience (collected and broadcast by the globally attentive CETI project). [29] These fathom-spanning low tones echoing in the deep, when first isolated by the military from the human cacophony of mining and atomic explosions, changed the culture of whale hunting.

Entering the field of relations automatically extends resonance beyond the human, opening conception to ideas about unheard but felt vibrations. If companion species dogs somehow sense human blood sugar levels before machines can—but not through any known chemical exudation—perhaps we should ask whether that shift is perceptible through canine attending to shared vibrational being (from an internal pulse of stressed fluids to an acoustic register that only a dog can hear). [30] Similarly, some tiny arthropods find their pollen source when the ripening plant’s oscillating molecules speed up and emanate heat disproportionate to ambient temperature—a kinetic differential the plant has evolved to emit, and the bug has evolved to sense. [31]

Field work and attunement to modest energies is how this science is done—and an embrace of resonance is part of that attunement. Signal thinking is reductive, sometimes necessarily so, to refine what may be a message. Those acoustics trade in frequency, Fourier transforms, algorithmic calculations in a mathematical brain, and the rule of neurons—these imagine a veritable deadroom for interiors primed to receive and decode. Reduction obsesses about signals, more or less well received, rationalized through Bayesian calculations, evoking Claude Shannon’s information science hieroglyph in which “noise” is mere interference. Resonance opens that black box to find everyone in it: dogs, whistles, whales, people, beetles, plants laden with pollen, and the innermost organs and fluids that resonate them together.

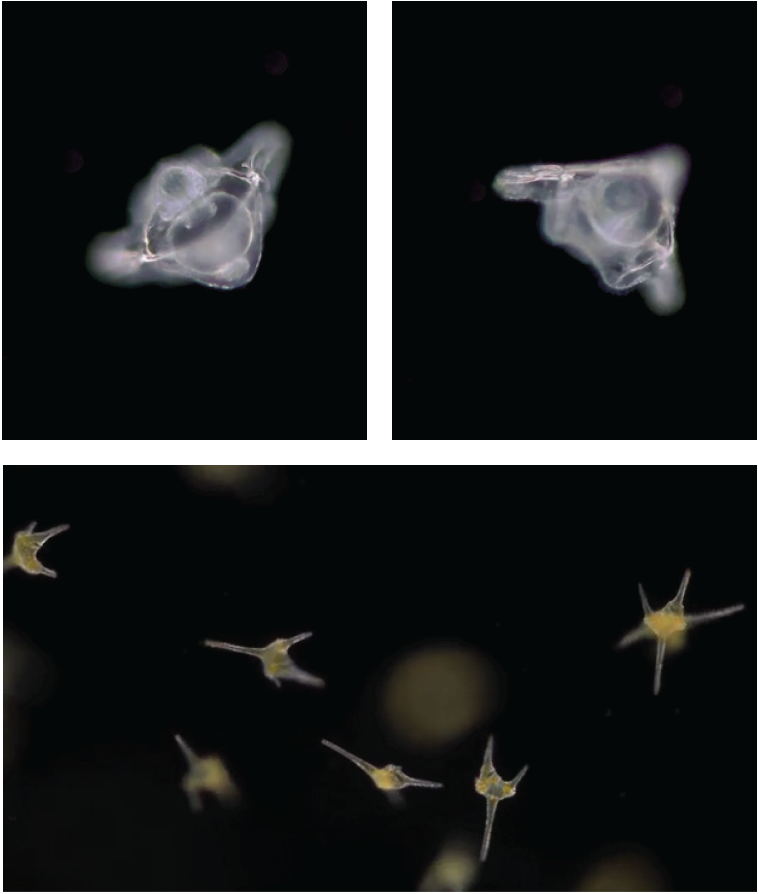

Figg. 7, 8 and 9 – Stills from Jana Winderen and Jan van Ijken, Planktonium, 2024.

Sound artist Jana Winderen plays the field. She often deploys hydrophones in the ocean—not to resonate by emitting sound, but to eavesdrop on the already resonant volumes of our planetary seas. Clicks and calls of more-than-human species that ply ocean depths are her quarry, but also the waves, icebergs, and rainstorms that alter its surface. In her most recent collaboration with Dutch filmmaker Jan van Ijken, Planktonium (2024), the two created a film but also occasionally perform live, weaving van Ijken’s microphotographic sequences of pulsating, dancing, and scintillating diatoms together with Winderen’s “soundcomposition” (as she calls it) layered in real time. [32] The oceanic sounds are trans-scalar, ranging from the clicks of feeding shrimp and (imaginatively) the tiny collisions of silicaceous plankton, on up to the depth-spanning cries of the great leviathans, whose lowest frequency calls are believed to travel refractively in ocean channels for as much as 10,000 miles. If humans only awkwardly attend to sound underwater, whales have evolved over millions of years to use the ocean’s miscible layers savvily for globe-spanning resonance. Boundaries between variable densities of ocean water (due to salt content and temperature differences) create the resonating conditions for SOFAR: SOund Fixing And Ranging channels that allow whales’ low frequency calls to bounce and propagate (e.g., resonate) without losing energy, for thousands of miles. [33] Encountering this field of relations, Winderen must edit out the growing cacophony of human industry in her recordings (“pile driving, seismic surveys, boat traffic”) to create her immersive, literally oceanic soundscape, letting us temporarily bathe in the liquid reality of a watery planet. [34]

In all of these instances, resonance in the field complicates reductive abstraction. Resonating experience puts us inside a lively, wet, fleshy, sympathetic, membranous, emotion-laden, visceral, risky and potentially “invasive” situation. Winderen’s sound art is decorous, letting us stay dry but immersing us in wet sonorities from delicate silicate clicks to the heart-wrenching echo of a SOFAR-propagated whalesong. But other forms of resonance can be experienced as violent—Goodman’s Sonic Warfare capturing the essence of intentionally disturbing and assaultive fields. Going back to Neuhaus’s “Water Whistle,” one reviewer identified an invasiveness to the situation, feeling that the resonating tones could not be dodged, they penetrated the bodies submerged in the volumes of New York City pools, whether they wanted it or not (ears have no lids and resonance penetrates without permission). [35]

Fields are thus differentially experienced. For Lucier, such relational resonance suffusing the listener is the whole point of I am Sitting in a Room: “the point at which a listener loses understanding of the words and the speech has turned to music … My work is not on a flat two-dimensional surface—it’s in the sound in the room.” [36] In one 2014 iteration of the piece, some in the audience could hardly bear the 45 minutes it took for the room to achieve full resonance, while I experienced the composition as generous, meditative, and transcendent. It was a suffusive variant on Oliveros teaching me to fly. I mentioned to the composer afterward that I had been anxious when a cellphone ring entered the rounds of recording-playback, but roomtone eventually overtook the resonant whole. “The room heals everything,” he responded. [37] An audist’s anxiety becomes resonant cure.

The emergent properties of resonance have, in this essay’s argument, permitted the switch from signal to field in our epistemological relation to vibration. Rather than compulsively decode sonic and subaural experience for ready meaning, resonance recommends recognizing attunement. Even the disruptive or unwelcome vibration (say, the violent grinding of magnets in an MRI machine that surrounds our blood-soaked bones with “magnetic resonance”) is a signal in context: a field of experience, a vibrational probe, open to aesthetic reflection. [38] Rather than reduce the “input” to an “output” that is interpreted only as signal received, an embrace of resonance releases us temporarily from the normative mind-body, inside-outside problems of philosophy. We can expand our reflections to consider membranous exchange and transduction.

Accepting our always-entangled relations in and with the planet and framing them as resonance may be an incentive to limit human blasts/drones/roars/drills/whines from the media we share with the more-than-human (air, water, ground). Sound art is good for this activity of sensitization and transformation. Learning to fly, to suspend ourselves in room-tone, to assume the planktonic scale of aqueous being and becoming, is to expand wildly beyond the signal. Re/organized and knit together by vibratory experiences, we all become “the sound in the room,” the arts resonating us into collectives, as the fluid creatures we are.

* I am grateful to Andy Graydon and the two extremely generous peer reviewers, who encouraged this art historian to tackle the expanding literature on listening and sound.

[1] “Resonance,” Oxford English Dictionary (2010). Beyond the OED, space must be construed as more than “void.” Space includes the air-filled and the liquid-suffused, even the molecular spaces between material solids resonates. With gravity waves, space may be seen to include vibrations of space-time itself, sonified to resonate beyond the detectors. See Stefan Helmreich, “Gravity’s Reverb: Listening to Space-Time, or Articulating the Sounds of Gravitational-Wave Detection,” Cultural Anthropology 31, no. 4 (2016): 464–92. For fluid-filled, see Nina Eidsheim, “Sensing Voice: Materiality and the Lived Body in Singing and Listening,” The Senses and Society, 6, no. 2 (2011): 133–55.

[2] Christoph Cox, Sonic Flux: Sound, Art and Metaphysics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

[3] “Reduced listening” was a concept innovated by French composer Pierre Schaeffer, identifying an approach to sound that defers decoding meaning, staying with the experience of the sonic object itself. Michel Chion offers this definition: “[reduced listening] focuses on the traits of the sound itself, independent of its cause and of its meaning. Reduced listening takes the sound—verbal, played on an instrument, noises, or whatever—as itself the object to be observed.” See Michel Chion, “The Three Listening Modes,” in Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen, trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 25–34. The model of reduced listening, in this essay, is suggestive but must be extended to the felt not heard. This essay does not align with affect theory, and in this I am with Kane: embodied cognition of the type I am describing is a continuum, and affect is an inseparable component. See Brian Kane, “Sound Studies without Auditory Culture: A Critique of the Ontological Turn,” Sound Studies 1, no. 1 (2015): 2–21.

[4] Harmut Rosa, Resonance: A Sociology of our Relation to the World (Cambridge: Polity, 2019).

[5] Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010).

[6] Salomé Voegelin, Sonic Possible Worlds: Hearing the Continuum of Sound (London: Bloomsbury, 2021).

[7] Thomas Seeley, Honeybee Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010).

[8] Daniel Heller-Roazen, The Fifth Hammer: Pythagoras and the Disharmony of the World (New York: Zone, 2011).

[9] Peter B. Denes and Elliot N. Pinson, The Speech Chain: The Physics and Biology of Spoken Language (Long Grove: Waveland Press, 2015).

[10] Veit Erlmann, Reason and Resonance: A History of Modern Aurality (New York: Zone, 2010).

[11] “In the cochlea of the internal ear, the ends of the nerve fibers, which lie spread out regularly side by side, are provided with minute elastic appendages (the rods of Corti) arranged like the keys and hammers of a piano. My hypothesis is that each of these separate nerve fibers is constructed so as to be sensitive to a definite tone, to which its elastic fiber vibrates in perfect consonance.” Hermann von Helmholtz, 1868 lecture on the human senses given in Cologne, Germany; quoted in Timothy Lenoir, “Helmholtz & the Materialities of Communication,” Osiris 9 (1994): 196.

[12] For where these objects “drifted” in the long nineteenth century, see David Pantalony, “Variations on a Theme: The Movement of Acoustic Resonators through Multiple Contexts,” Sound & Science (July 17, 2019).

[13] See Joshua McDermott, neuroscientist of audition, presenting in the “Sounding – Resonance” segment of the MIT symposium Seeing, Sounding, Sensing in 2014 (October 23, 2014).

[14] Sara Hendren, “The White Cane as Technology,” The Atlantic, November 6, 2013.

[15] “For … one week of lullabies for roux (2018), Kim commissioned a group of friends to create alternative lullabies for her daughter, Roux. Adhering to a set of rules including directives to omit lyrics and speech and focus on low frequencies, these compositions serve to vary what Kim has termed the ‘sound diet’ for her child, raised trilingually in ASL, German Sign Language (DGS), and German, and to place equal weight on all three in a culture that tends to ascribe lesser relevance to signed communication.” See “Christine Sun Kim: Off the Charts,” MIT List Visual Art Center (accessed June 17, 2024).

[16] See Steve Goodman, Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009).

[17] Voegelin, Sonic Possible Worlds; Dylan Robinson, Hungry Listening: Resonant theory for Indigenous sound studies (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020).

[18] Tanushree Agrawal and Adena Schachner, “Hearing Water Temperature: Characterizing the Development of Nuanced Perception of Sound Sources,” Developmental Science 26, no. 3 (2023): e13321.

[19] While Voegelin is clearly important to this argument, I bring feminist critique and queer theory to bear on the “hard” sciences of physiology, which systematically downplay the role of fluids in audition. Beyond the physio-mechanisms of the ear, the present essay aims to go beyond the audist world of “hearing” to visceral sensing of resonance. There is bone conduction, but also vibrating, fluid-filled, embodied organology.

[20] And how the watery body produces them! The beat of blood, cilia-propelled mucus and lymphatic fluid, doses of timed glandular secretions, and the under-discussed push of chemicals necessary for intra-synaptic propagation of nerve “impulses,” all are fluid pulsions of one kind or another.

[21] The author’s chart of how anatomists of audition describe functions and anatomical features of the outer, middle, and inner ear, with an announcement of the medium in which soundwaves are being passed along. This diagram is informed by, but contrasted with, two sources on human auditory anatomy and function: Peter B. Denes and Elliot N. Pinson, The Speech Chain: The Physics and Biology of Spoken Language (Long Grove: Waveland, 2015); David M. Bruss and Jack A. Shohet, “Neuroanatomy, Ear,” StatPearls (2023). These sources are composited as critique of hard and fuzzy logics via decades of teaching the MIT interdisciplinary subject Resonance with my esteemed colleague Stefan Helmreich. Italics are my gloss on the components, naming the fluid that usually goes without naming.

[22] Decoding the mystery, marine biologist David Gruber claims to translate cetacean communication as language and through LLM (large language models) based on human abstract syntagms. His focus is primarily on sperm whales, for which see his CETI project which uses machine learning to store, compare, and tag cetacean soundings for human understanding (accessed October 22, 2025).

[23] Neuhaus, speaking in Michael Blackwood documentary New Music: Sounds and Voices from the Avant-Garde New York 1971 (2010) (accessed September 30, 2023).

[24] Max Neuhaus, quoted in Jonathan Cott, “Max Neuhaus, the Floating Composer,” Rolling Stone, August 19, 1971, 18.

[25] Cott, 18.

[26] “Actually, when you arrived down under, you heard 10 notes sounded simultaneously, each element of the chord varying in pitch according to the pressure of the water being forced through the respective whistles. […] Changes were very gradual, the sound emerging as a steady drone, rather than music with shape or line. It was quite pretty, too, if you like drones.” Robert Sherman, “N.Y.U. Concert Wets Whistles for More,” The New York Times, May 9, 1971, 61 (accessed 30 September 2023). This version of “Water Whistle” was offered in a pool at New York University’s Hayden Hall from 9 pm to noon the next day, per Sherman.

[27] Cott, “Max Neuhaus,” 18.

[28] John Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writings (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1961).

[29] Joan Jonas has worked with David Gruber and CETI (Cetacean Translation Initiative) since 2017; their most recent collaborative work appeared in Jonas’s commission from the New York Museum of Modern Art, To Touch Sound (2024), a multiscreen video incorporating CETI footage with attendant sound of sperm whales.

[30] I am grateful to the provocation of Hélène Mialet, whose anthropological work on the inter-species collaboration known as “Dogs for Diabetics” focuses on the scientifically unknown reasons for trained dogs’ capacity to sense low blood sugar in diabetics 20 or more minutes before the glucose monitor in their veins can do so. While Mialet focuses on the nose, she was open to my speculation that olfactory chemistry is only one canine sense for attunement to their beloved partners.

[31] See the work of evolutionary biologist Wendy A. Valencia-Montoya, who studies plant-insect symbioses. Valencia-Montoya et al. “Infrared Radiation is an Ancient Pollination Signal,” Science (forthcoming, accepted Fall 2025). In this research, scientists are describing the relation between the genus Zamia (Zamiaceae: Cycadales), ancient dioecious plants (dimorphic between male pollen-producing cones and female ovulate cones), and its pollinators the Pharaxonotha beetles. The scientists report that the cyads differentially heat up in a circadian rhythm (afternoon male first, then in early evening female), to bring the beetle pollinators from the pollen source to the female receptor. Heat-detection is accomplished in the beetle through the most distal tips of the axillary antennae, which are enriched with sensilla. These vibratory relations are energetically expensive, yet evolutionarily conserved over at least the past 200 million years.

[32] Performed at the International Documentary Film Festival in Amsterdam on 22 November 2024 (accessed 23 November, 2024).

[33] “What is SOFAR?,” National Ocean Service, June 16, 2024.

[34] Philosophically-trained physicist Aleksandra Kruss describes this unfathomable assault in “Underwater Sound: Discovering a Liquid Reality,” Leviathan Cycle (accessed November 23, 2024).

[35] “Describing Neuhaus’ 1974 series of 21 installations called Water Whistle, in which submerged sounds were emitted in various New York City public pools, Al Brunelle wrote in Art in America, ‘Whereas the sense of sight is generally fixed to what is external—‘out there’ in the field of vision—sound takes place within the ear, so it is more invasive and fraught with consequences.’ ” See Nancy Princenthal, “The Sounds of Violence: Max Neuhaus’ Project,” Artforum (May 1982): 70.

[36] Alvin Lucier and Brian Kane. “Resonance,” in Experience: Culture, Cognition, and the Common Sense (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 139–40.

[37] Alvin Lucier, discussion with the author following the performance of I am Sitting in a Room at MIT in 2014, as part of the Seeing/Sounding/Sensing symposium at MIT.

[38] See the work of composer and sound artist Arnold Dreyblatt. Evan Ziporyn, “Visiting Artist Arnold Dreyblatt’s Magnetic Resonances,” MIT Center for Art, Science & Technology, March 19, 2013.