ARTICLE

After Alerts

Katherine Behar and David Cecchetto

Sound Stage Screen, Vol. 4, Issue 2 (Fall 2024), pp. 63–88, ISSN 2784-8949. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. © 2025 Katherine Behar, David Cecchetto. DOI: https://doi.org/10.54103/sss30337.

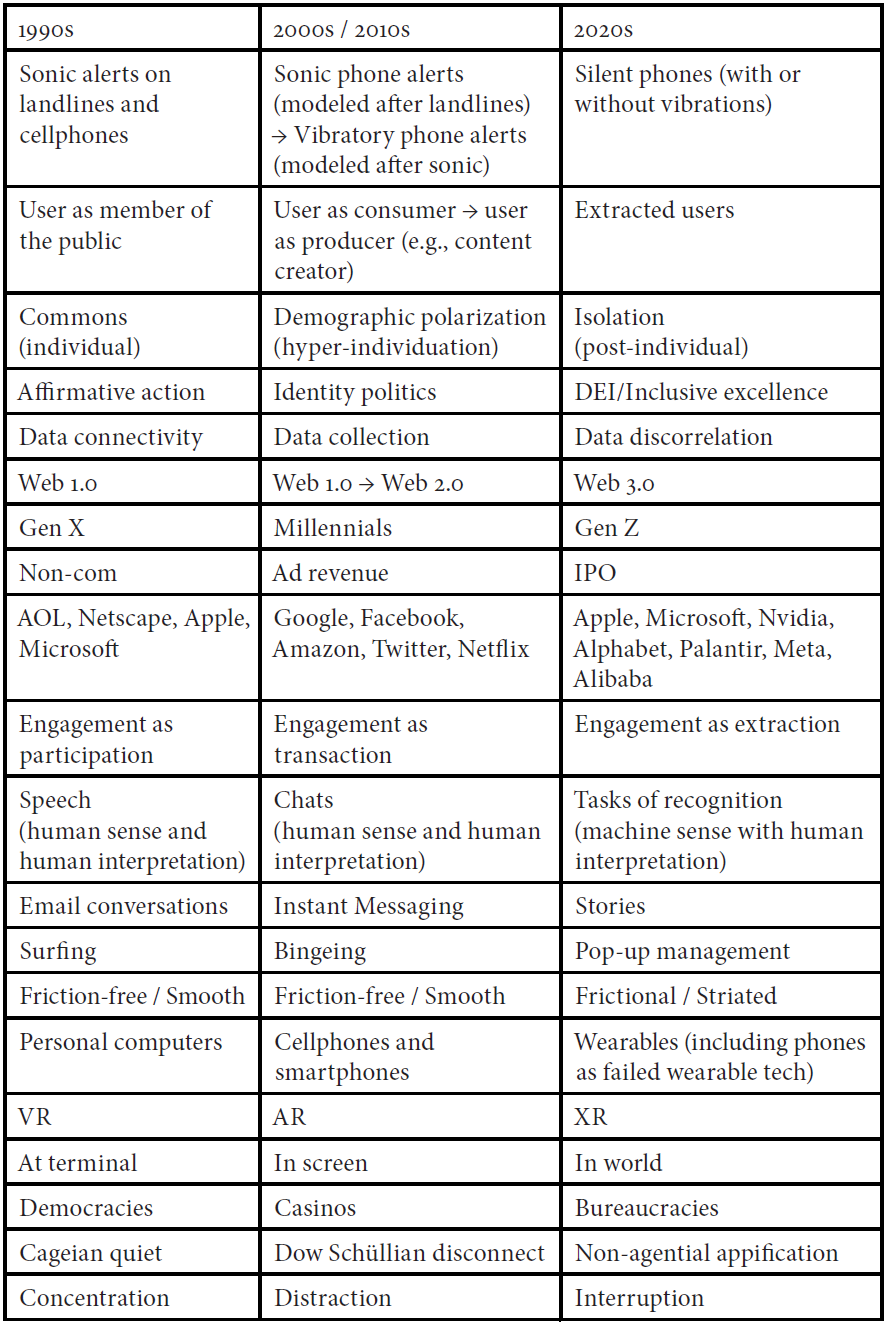

Before we begin, we offer this speculative schema:

“Please silence your phones. The performance is about to begin.” Sitting in the theater with the lights dimmed, this announcement signals a moment of attentive transition: the quiet cacophony of the audience having been suitably silenced, whatever follows will reward heightened focus.

Or: A comedian heckles an audience member who has just been singled out by the tinny, compressed version of “Don’t Stop Believin’ ” crying out from their coat pocket.

Or: A student goes ghostly white as, surrounded by 200 of their peers in a biology lecture, an unmentionable YouTube video starts playing out loud.

Or: A synthetic shutter “click” issues from a smartphone camera as an audience member captures a particularly precious and delicate moment of a theatrical monologue, having forgotten to silence their phone.

Or: Taxiing to the gate and switching a phone off airplane mode, an overlapping cascade of messages comes in faster than their “dings” can echo, as a full conversation that unfolded during the flight arrives stumbling on top of itself, all in one go.

Or even: the humming buzz of a phone case skittering across the burnished top of a conference table, silenced but still vibrating insistently as a call comes in, breaching the performative perimeter of its “do not disturb” settings.

While phones still go off in fumbled-for bags with semi-regularity at predictably inopportune moments, these out-loud vignettes are part of a sonic ecology on the wane. Whereas an iconoclastic Gen Xer might have designed their own ringtones to signal their difference from the corporate morass of big tech, even that decision is now revealed to be in concert—literally—with that which it would oppose. Anyone born after 1995 just keeps their phone on silent, right? [1]

How then to characterize the current sonic ecology of always-already-silenced phones? How do we listen to the silence of phones, and what do we learn from doing so? These are enigmatic questions, but the distributed character of listening means that the paradigmatic object of listening is no object at all. And so, listening offers a suitable approach because it is always aimed at more than one thing, attuning to distributed agencies that take shape as patterns that are themselves caught up in the worldings of specific situations. Constitutively, the remit of this practice exceeds anything as simple as what sound “communicates.” [2] Listening is not simply the addition of attention to physical hearing (contra its quotidian use). Instead, it is a delicate looping of comings and passings that pattern incipient subjectivities by relaying between affective and experiential dimensions. [3] To listen to the silence of smartphones, then, is to tap into technoculture’s choreosonic perceptibility, the ongoing movements through which worlds become the felt selves that we are (and vice versa) independent of our awareness. [4]

Our method joins ample precedents: what is Debussy’s famous declaration that music is the space between the notes if not an implicit injunction to listen for a musicality in the coherence of a collective temporal distribution rather than in any particular moment? Further, and more evocatively, poet CAConrad describes a practice of “flooding their body” with field recordings of the natural environments of extinct species. Notably, they do not situate this as a nostalgic practice but instead as a means of loving the world in its presently mediated forms. [5] In these and other cases, listening figures a pathway that feels—even if it can’t register—that which is being experienced phenomenally without being explicitly sensed. This is not merely a result of limited sensorial sensitivity to the restricted range of audible frequencies, but also and more profoundly it stems from scalar constraints such as the broader distributions of cultural tendencies we are tracking here through silenced phones.

If listening involves attuning to such epistemic registers, understanding this new sonic context requires asking how the broader ecology of phones has changed, particularly in relation to attentional economies. An alert, after all, does what it does to call our attention to the fore, superseding something else. But to listen to these alerts is to supplement the autonomic responses that they individually elicit with an attention to the conditions and suppositions that such responses entail—affectively, subjectively, and socially. And this is all the more the case in their contemporary silence: to listen to the silence of silenced phones is to attend to the inclusions, exclusions, tempos, rhythms, and textures of a particular register of contemporary sociality.

It’s tempting to theorize the diminished presence of the alert as an attempt to quiet the oft-lamented culture of distraction associated with internet culture. [6] Certainly cellphones and their smarter cousins have contributed to an audio landscape of audible distractions. Prior to their ubiquitous pings, such constant hails would be almost inconceivable to most of us: as with the development of a sense of propriety around when to answer a ringing landline (or not), we had to learn practices and principles of attention in the face of this new clatter. Yet distraction presumes an object of concentration and a subject fundamentally capable of concentrating on something somehow. When we silence a phone, it is because we know what we want to attend to, so we make decisions in advance to secure that goal (this is what each of the above anecdotes demonstrates).

In this sense, the silence of silenced smartphones is fundamentally different from the silence that preceded the possibility of such pings, like the silence of a home is different before and after the death of a loved one. [7] Whereas an earlier silence contextualized instances of distraction (i.e., pings), something different is sounded today. After all, even with so many phones now silent, we still can’t get anything done. We may be less distracted, but we feel more frustrated by something else in play.

And so, our speculative hypothesis: rather than our intentions being subverted by distractions, our attention today is focused but constantly interrupted by an unrelenting onslaught of minor barriers that mis- and redirect our action, diminishing our interactive agency.

Here’s the scenario:

We are trying to make a dinner reservation. We open Google Maps and search for nearby restaurants. By way of Google Maps, we visit a likely contender’s website. The website content is blocked by a banner that asks us to accept cookies or change our preferences. We first elect to change our preferences and then proceed (on principle) to decline non-essential cookies via individual toggles. However, to view the menu, we need to leave the website and download the restaurant’s proprietary app. This requires a visit to the App Store and a sign-in. We must first open and enter credentials in our password manager, which then populates our App Store login information, permitting us to download the restaurant app. Once the app is successfully installed, we tap again to open it and are prompted to make an account for which we must switch over to our email app to await a one time use code. When it arrives, we enter the code in the app to complete our account registration, and upon doing so we are immediately greeted by offers to subscribe to alerts and share our location, both of which we tap to decline. We can now enter the app to view the menu and confirm that this is in fact a place our dinner companions are likely to enjoy. However, to make the reservation, we are redirected to a third-party app through which the restaurant manages bookings. Fortunately, we already have this app, but it requires another password manager sign-in. This leads to dual-factor authorization (2fa), so we await a text message. We receive the text message, and we then tap to automatically populate the one-time use code sent to our phone into the appropriate field in the reservation app on the same device. Finally, we use the app to select a day, time, patio preference, and the number of people in our party. We make our reservation. Having done so, we receive an automated text message confirmation of our reservation details to which we must reply “1,” confirming the confirmation.

Throughout this tedious twenty-eight step transaction, not once were we distracted. Rather, the heightening frustrations reinforced our focus. Had a text message arrived in the midst of this exchange, we would certainly have ignored it. With the escalating anxiety of constant interruptions intervening against our intentions, a mere message could not possibly distract us. Instead, we remained dedicated to accomplishing a single task. The mounting aggravations increased our resolve, making us less prone than ever to distraction. This is both sonically and affectively different from the distractions of ringtones and vibrations.

Silenced phones don’t make sonic space for concentration, then, but are a symptom of a larger attentional shift from a culture of distraction to one of interruption. Distraction had its pleasures: the black holes of binge-watching, the hours lost to triumphant fact-finding in the obscure niches and outer reaches of the interwebs. [8] Such indulgent excursions are increasingly a thing of the past, with the depth of previous internet dives pancaked into the equivalent of a discount shopping center. [9] Stuffed with no-name schlock, the individuality of brands (no less of people) has no meaning and promises no rewards. Now, far from rewards, our online experiences promise punishment. Experiences online are terrible for being peppered with myriad interruptions: from pop-ups to sign-ups, 2fa to location sharing, click-throughs to cookie consents, and more. [10] To dig out the tail of a reference—never mind to make a dinner reservation—requires surmounting an inestimable stack of prerequisite micro-interactions (i.e., clicks) that stands in the way of the task at hand and stalls the smooth sailing of what once was surfing. [11] These interruptions shift the delay of accomplishing a task from a quantitative problem to a qualitative one. That is, what it means and feels like to go about a task is itself changed by virtue of the impossibility of performing it without interruption. [12]

Perpetual awareness of inevitable interruption is the only thing that carries through actual interruptions uninterrupted.

Why call this interruption? To signal a distinction from both the question of an autonomous self-possessed subject (who could be distracted) and the newly emergent (and oft-discussed and celebrated) automated decision-making. The experience of quotidian computing today isn’t captured by either of these paradigms. And yet the design history of smartphones reveals that this has always been the case: our decisions about use are always already shaped (though not determined) by the corporately designed imaginative spaces opened in our interactions with our devices. It is only because we can abstract a desktop from an actual piece of furniture that we can make sense of and act within a desktop computer. [13] Likewise, it is only because we can think of an app as a real and existing entity that we can attune to what it wants from us. People who have lived in different regions or countries often feel how design assumptions—for better and worse—that seem natural in one place don’t hold in another. But no need to travel: we only need be alive and digitally active long enough to feel how our particular dialect is replaced by another, less comprehensible one. To wit, everyone’s phone is on “silent” now.

What changed? Since at least the early 90s, interfaces were (in principle) designed to be as smooth as possible, to the point where most technology designers would accept in advance that the perfect interface would be invisible and unnoticed. [14] For example, early iterations of web design prioritized frictionless passage through online content. Pre-dotcom crash, designers contending with sluggish dialup speeds sought to minimize the frustration of slow-loading pages, so on “well-designed” sites important content loaded first and an “as few clicks as possible” methodology held sway (if not by making it as easy as possible, how else could the general public ever have been convinced to become users, lured into participating in the nascent commons of the then-new-fangled World Wide Web?)

Such early internet mores shaped and were shaped by the development of ubiquitous computing, which extended these principles into a new, distributed form of computing that not only dispensed with acute attention, but even defied notice. Rather than a terminal-bound attentive activity, technology was willed to disappear. Computing’s becoming-invisible was accomplished by its integration into everyday objects, a legacy that continues today as the Internet of Things. [15] To the extent that computers were conceived as tools, their design aimed to facilitate any task to which they were put with seamless transparency.

This approach was so naturalized that its politics became the subject of perhaps the central debate of media theorists, encapsulated in Friedrich Kittler’s famous insistence that interfaces are fundamentally ideological. [16] In this view, meaning is primarily produced at the operational level (i.e., code) of a computer rather than in the semantics of its interface, so that to use a computer responsibly requires being able to intervene in the former rather than just the latter. This matters, for Kittler and many others, because by designing “natural” interfaces that make computers usable “out of the box,” technology manufacturers were widening the gap between these two registers, thereby foreclosing in advance the most meaningful forms of engagement users could undertake with computers.

This insight led to numerous laudable initiatives ranging from open source software to “right to repair” laws and various DIY technologies and protocols. At the level of design, however, these initiatives have proved largely unsuccessful: consumer computation today—in all its guises—is performed by machines that are black-boxed. This is truer than ever if we include as part of black-boxed computation not just the hardware we buy as stand-alone machines, but software [17] and increasingly ubiquitous AI technologies, whose power lies in the fact that the ways they work can never be accessible to human intervention at the operational level (hence “prompt engineers”). Whether Kittler was correct or not (an open question), it is indisputable that computers today work more than ever to nudge actions and decisions in ways that are both unnoticed by and literally inconceivable to their human users.

But actually, the disappearance of interfaces didn’t happen… or at least, it isn’t all that happened. At just the moment Weiser predicted, when terminals have been replaced by everyday devices—like wearables, like the Internet of Things, like smartphones (of course)—interfaces have not vanished into the background. Quite the opposite. Compared to the minimal clicks of early web design, today’s web pages insist on failing to load, often in the most obnoxious fashions possible. [18] Any online task requires slogging through myriad micro-interactions, all of which interrupt intent. Somehow, this era of completed interface—this moment when computers are everywhere and consist in interfaces all the way down—still requires an unprecedented amount of clicking. Perhaps we should have expected as much, given consumer technology’s unerring ability to land on the worst of both worlds (see Elon Musk, entrepreneurial technologist and political activist). Nonetheless, we might note just how annoying this is and, much more seriously, what a degraded and degrading individual experience it amounts to for all of us, since we are all perpetually conscripted as users.

Ironically, the seamless invisibility that designers promised is met with silence, but this silencing (of phones) is paired with an interface that loudly interrupts. While it’s sonically silent, it’s far from “disappearing.”

Of course, phones make plenty of sounds besides alerts. In interface design, sounds are usually deployed either to confirm that a user’s action has been correctly registered or to solicit a user to take action. In the first instance, think of the “tocks” of touchscreen typing absent the mechanical click of a keyboard key. In the second, consider the “pings” of a message arriving, its preview banner flashing briefly on the homescreen to initiate a knee-jerk series of actions: head pops up, eyes search for phone, face unlocks screen, user reads message. By both confirming and soliciting, interfaces interpellate users as communicative subjects in dialog with and within a technical ecology that affirmatively sounds out their position in it. This is interface design in service of a vision of interactivity that hinges on agential subjecthood.

The tock of typing renders an otherwise inscrutable activity meaningful, inviting us to imagine (correctly) that the glass screen is also something else. Whatever it is, that something else is where we pursue meaning. However, a tock is no longer necessary because interactivity is now also the site where the opposite happens: otherwise meaningful activity becomes inscrutable in the mire of interruptions. This is why, like alerts, so many people have stopped tocking: keyboard tocks can be turned off only if the touchscreen’s sounds have been internalized. The silence of phones is sounded as a voice whispering inside our heads. A tinnitus of the times: unheard by others, unverifiable but undeniable, it is at once deeply psychological and materially of the broader world. It is unheard, and yet we can’t but listen to its forceful mixing of physical and psychological worlds. Yes, this internalized voice [19] mouths the “tock” of interactivity, but also something else: the interruption of our agency, itself a symptom of the internalization of the impossibility of uninterrupted attention. Who can think with all this (tinnital) tocking?

Even absent tocks, we are hardly wanting for ways to know that we haven’t achieved what we’re trying to. If anything, being constantly stymied by interfaces means we rarely do what we set out to. Rather than affirming that we are operating within a system as happily interpellated users, silenced design elements only affirm that we are caught up in a system that operates against us, against our will, against the myth of interactive agency. We don’t need not to hear a tock to know we haven’t achieved our intention, to know our networked action is meaningless. Perhaps we didn’t type correctly, mis-entered a password, typed in the wrong form field, auto-filled accidentally. Or else, we respond as if a bureaucratic behemoth adjudicates from across the interface. Did we slack off in catching all images showing sidewalks? Why hasn’t our 2fa SMS arrived? Are we still logged in to the wrong account? Maybe we need to pause our ad blocker? Design (and the consumerism it caters to) leads us to think the smartphone’s smartness is there to make us smart, but its smartness is in service of a larger network that reduces us to headless clickers. We are animated by an agency we never had, viscerally felt as something that we did or will or could have… just as soon as we successfully click through.

Hence, the changing norms and presumptions of interactivity reveal a change in subjectivity that goes hand in hand with the affective shift from distraction’s pleasures to interruption’s frustrations. This new subjectivity signals a larger interruption of agential subjects writ large. Just as the alert signals (to) a subject whose attention it requires, the broad cultural silencing of alerts is only possible for a kind of subjectivity that has already internalized interruption. That is, the agent who does is itself interrupted. An alert summons interaction. But interaction is distributed among gestures/tasks/measurables that need only register a doing in a database; as data collection gives way to data discorrelation, [20] data need not cohere as an individual profile associated with an agent. [21]

As a result, the imagination of the erstwhile subject who would conceive a task in the first place has, by virtue of being always already looped into this interruptive circuit, taken on a distributed and ineffectual character so as to align with this ecology. [22] What does that sound like? Nothing. Certainly not the buzzing silence celebrated by Cage. [23] Instead, it’s the existential blah blah of commercials and television transposed from the 20th century. When this emptiness reappears as the sound of silent phones, it becomes worse: the agential nothingness of the listener.

Wedded to the addictive pulses of dopamine release, the background buzz of addictive nothingness circuits new media technologies through the (non)thrills of gaming. In Natasha Dow Schüll’s unflinching account, casino algorithms and architectures work in concert not in the service of gambling (as it seems), but instead according to the demands of the human hormonal systems they recruit to service capital. [24] The question of whether we like slot-machines is unrelated to whether we will continue to pull the handle, and the interface design of algorithmic gambling leverages this lever-habit, even as levers themselves are replaced by a digital hit (cousin to the click).

It’s not the interface that disappears, but the agent at the interface who fades away. Or more properly, the wincing embodiment of that agent: gamblers wet themselves at the slots, so locked into the algorithm’s rhythms that they can’t break away from their stools for a body break. [25] Despite derisive tropes, these folks are not losers—or at least no more than any of us. They are not losers because they have no pretense of beating the machine. The vacuous nothingness of fulfilling the timing called out by the machine is an end in itself. They are losing money, but they are winning the pleasure of distraction in spades. What is winning if not the luxury of opting out by checking out? It’s a win when these nothings distract soothingly from the somethings of life better left behind.

If Cageian quiet heightened attention to the world outside, to the abundant sonic surround, then Dow Schüllian disconnect puts that surround (and the perceiving subject it centers) on mute, folding in on itself (on oneself). Even if it looks like total focus, this kind of utter absorption is of the same continuum as distraction. It is only possible for hyper-intact subjects: those very subjects who are now, we propose, interrupted.

Agential interactivity turned the Cageian surround around, making the cybernetic self—a self locked into the feedback loops of technical circuits—into its own landscape. This inside-out interior, subjective landscape is a landscape for extracting value. The internalization of alerts, however, marks a new turn in that extractive logic made possible through a redesigned form of interactivity—appification—that does not cater to agents but rather dismantles agency.

When the sonic abundance of silence as the Cageian surround is extracted as the ho-hum buzz of emptiness, addictive nothingness is not what’s left after extraction but instead the subjective frontier where this particular form of extraction is possible. In that case, if our speculative thesis holds true, will future casinos—at the avantgarde of attentive disorders—soon forego all of their distracting bells and whistles, their interruptive ecology having been fully onboarded onto would-be gamblers?—oh wait, this is already the case: as of February 2024, over 80% of betting in the U.S. happens online, the majority of it via mobile phone. [26]

In sum: If interactivity, with all its out-loud beeps and dings, follows from a lineage that prioritizes agency (the agent summoned and confirmed by those sound effects), then the silencing of interactive sound effects announces the emergence of a different, non-agential attentive subject. This subject pays attention without the pathological refocusing of constant pings. If pings refocus individual agency and attention by confirming and soliciting, those sounds are part of an attentional economy that delivers eyeballs (and eardrums) to advertisers based on an antiquated assumption that users are worth it: that our attention has value. [27] These pings distract, leading us on and into pleasurable time-sucks that fuel self-satisfied complacency. By contrast, interruption characterizes the devalued sonic subject of an online experience, a vibratory ecology that has been fully internalized so as to put the online self itself on mute. Just as Marx made clear that the factory conceives workers in the image of machines, so does this interruptive ecology make discorrelated clicks of us all. [28]

What is perhaps most frustrating about the dinner reservation scenario is that a direct alternative remains in recent memory, when a reservation could be attained quite quickly with a simple, focused action: calling the restaurant. [29] Nevertheless, we resign ourselves to no-way-out frustration online, having internalized a structure of interaction that doesn’t even deign to distract us with dings. We know perfectly well what we want to do, yet can’t do it because we are constantly interrupted. What we want has become irrelevant; the specifics don’t register anywhere because all that matters is that we have wants at all insofar as our having them fuels an impulse to continue with our actions.

The asocial totality that results from this dividuated status quo reinforces the irrelevance of personal pleasure and even the pretense of agency. Parsed as “grammars of action” [30] that can be captured as measurables, personal actions are disassociated from intentions and transformed into collectivized data sets that train machine learning systems, dream up demographics, and hook us into the compulsive circuits of communicative capitalism. [31] This further signals a shift away from personal data that needed to reference an individual’s quirks for targeted ads; instead, anonymized data feeds into generic systems in which individuals are as irrelevant to marketing as their desires. We are no longer consumers who might be catered to, nor content creators whose impulses count for something. We ceased being members of the public long ago because those social actions are ungrammatical in today’s technical milieu. Now our engagement has little to do with participation or even transaction because our opportunities for interactivity are foreclosed even further. Instead, to be a user now resembles the role of Mturkers who are made to produce value in the form of Human Intelligence Tasks—so called because its taskness divests the person undertaking it of exactly their human intelligence.

In this way, the silencing of phones signals an evacuation of desire, alerting us to the transition from an economy of distraction to an extractive economy of interruption. This silent sonic ecology rehearses the primordial role that technicity plays in our bodily arrangements, and the porousness of bodies. [32] Yet, while the fuzzy reality of multiplicitously technical bodies is often noted, it’s impossibly slippery to hold onto: theory rarely tracks the perceptual shifts that concepts require. [33] We insist that this plays out as a certain kind of internalization in the present interruptive moment of smartphones: the silence of contemporary phones sounds an absent dial tone that drones in the space between our ears.

After the Death of the Social (Again)

A focus on distraction distracts. It keeps us from noticing that, at base, today’s internet operates bureaucratically: it takes our impulse to act (e.g., to seek out some information) and routes it through a complex of clicks, links, etc., that sucks the energy out of us. [34] We know this feeling from the old days of mindless waiting punctuated by traipsing drab corridors between offices only to wait again (which continues now, but in and as an historical form), or hours of banal hold music sounded through tinny telephone speakers only to be disconnected on transfer. [35]

We also know that bureaucracies enact power discrepancies: on one side, an entity of unknown size, the workings of which are occluded; on the other, individuals who need something that can only be achieved by persisting through these unnavigable channels. Crucially, though power is in the bureaucratic room (or, perhaps more appropriately, the work-from-home office), it is always diffusely so: we might call it architectural in that it conditions our activities to preclude any genuine encounter. In short, bureaucracy is a technology for maintaining the status quo, taking any individual’s impetus for action and making sure it is utterly exhausted before it can have any effect. Political power peters out once channeled into the Kafkaesque labyrinths of institutions. Desire for change—real change—withers on the vine, or rather withers in the waiting room for the umpteenth time. [36]

Online interruption doubles down on this bureaucratic logic by leveraging the solidity of its status quo power discrepancy to activate protocols of bald extraction. Harvesting energies further consolidates power. Every click gives more information—tracking, demographic, timings, and otherwise—to a network that’s wholly indifferent to any actual desires that may have instigated clicking to begin with: everything that can be measured is, and what can’t be is so starved of air that it ceases to exist. The system is working precisely as intended, just not by any individual. We all know that everything everywhere is being tracked, and that this extractive tracking services big tech (which is, increasingly, big everything: the four largest companies—by market cap—are presently Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Alphabet). [37] We’ve all been conscripted into this exchange: we trade a portion of our privacy and autonomy for the ability to do things online. [38] If capitalism has long made hypocrites of us all, [39] the contemporary internet is its nadir (or zenith, since the world is upside down), taking hold at the very incipience of our cognitive activities. [40] This is manifestly terrible, but at least it used to be fun.

Because it’s really not fun anymore! Not just in the larger sense of existential dread that has long been in the mix, but even at the basic level of stimulation. Kafka’s twentieth-century bureaucracy resounds as the muffled reverb of closed interior spaces, with any signal muffled to the point of indiscernibility; the present inward turn articulates this instead as an almost total inaudibility—a social anechoics. [41]

As with pleasures, displeasures speak in highly specific dialects, latching onto the bodies, materials, histories, and concepts that shape them. Being online in today’s interruptive ecology offers a twofold displeasure: on one hand, the short-circuiting of distractive pleasures into the banal slop of a consumerist internet, [42] and on the other hand, the visceral frustration of not being able to get anything done. The former is a lost cause: once online networks became THE INTERNET, a form was inaugurated that was never truly social and is therefore politically impossible to reclaim as a public space. The latter is still a developing threat: that we feel exasperated making a dinner reservation signals that this crappy, boring, extractive future isn’t yet fully scripted. Feeling out of sorts signals that we are not fully absorbed into the setting in which we act, and that other actions are at least potentially sensible.If the situation is to be recovered, such recuperation will not involve interpreting or resolving this feeling of frustration, but will issue instead from the force the feeling exerts. [43] (Reader take note: there will be no recovering from this.)

Because make no mistake: the interruptive internet is in danger of being fully naturalized, and once it is we will be in a culture of completed interruption. If, as we contend, our technologies are seeping into our psyches to remake us (even as we remake them), soon our subjectivities and our socialities will both work according to the same logic. What will happen when the norm is to think, feel, and act interruptively? What will happen when we are no longer frustrated by being delegated the task of interpreting what our computer wants and acting accordingly? When it feels normal to act as human hypographs offering pop-up menus of auto-complete options for our computers to choose from? [44] Minus frustration, the alibi of a silent phone is no longer even needed, and sociality is (re)conceived in the image of extracted data. Identities (nevermind “people,” that long lost concept), were already reductive. Now they are mere placeholders for extractions to come. These extractions transduce the indeterminable possibilities of collective energies into a predetermined post-social status quo.

So here’s the scenario again:

Instead of making dinner reservations, we opt to meet up with friends for

drinks sometime the following week. Everyone is excited at the prospect, but

no solid plans are in the offing. Precise timings and locations remain in

the air. Unfolding over days, we absorb a continuous stream of proposed

changes and equivocations. Only in the final moments before getting

together, do these eventually give way to updates and assurances:

“running late”…

“on my way”…

“so sorry brutal day :/”…

“parking!”…

“omg slow train”…

“10 min”…

“see you soon”…

“almost there”…

It’s not just that the (silent) group chat never ceases, but that virtually all the messages disclose an interruptive sociality. [45] Our social interactions exist in an interruptive ecology that accepts in advance that energetic impulses (like social invitations) will both be routed through endless detours and subject to an extractive ethos. The latter, in this case, consists in the mining of sociality to improve the efficiency of errands that extend the consumptive possibility space at the expense of a social one.

This interruptive sociality also suffuses political space, where any impulse towards justice is met with a similar rerouting. Whether opposing a genocide or advocating for the job security of contingent faculty, an agential impulse towards justice is most often constituted in the bureaucratic terrain of interruption. In this case, at least we have a word for the slacktivist silencing of political action: clicktivism. [46] But this term implies that the problem is in the clicking, whereas we maintain that clicking is the symptom of an interruptive political ecology.

So let us return once more to the attentive transformation we are identifying as now underway. As we move from attentive distraction to attentive interruption, we move affectively from distraction’s pleasures to interruption’s frustrations. Further, we move from an online modus operandi that functions through the individual (an agential subject motivated by desire) to one that works despite the individual, or better, that dissolves the individual into discorrelated data gestures to be reassembled into an asocial totality. This totality is not big data as soylent green (i.e., made of people). [47] Yes, individual participation is involved, and yes, it amounts to a totality, but not the totality of the social. As we are constantly reassured by data privacy notices—anonymized data cannot be reverse engineered.

This interruptive circuit is how and where and why we submit to bureaucracy. Or rather, how not-quite-bureaucracy in its contemporary interruptive appearance submits us—our attentions, our interactions, our agencies, our actions, our socialities, and our unscripted futures—to its own extractive imagination. [48] If sonic metaphors seem perfectly suited to our times, this should give us pause: after all, what is the status quo but a description that denies its own prescriptive agency? [49] Likewise, if silencing our phones comes to seem only natural, such silence is the sound of the interruptive circuit closing.

[1] We are grateful to Fee Christoph for this observation.

[2] The previous phrasing is borrowed from Nathan Snaza who, citing David Cecchetto, takes up the question of listening in conjunction with scholarly discourses on the concept of resonance to make the point that listening is “about how distributed agencies take shape, as patterns in the ongoingness of worlds, in situations of relation, of touch, of haptics that include the sonic precisely as a field that exceeds anything that might […] be as simple as what sound ‘communicates.’ ” Nathan Snaza, Tendings: Feminist Esoterisms and the Abolition of Man (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2024), 89–90.

[3] Patricia Ticineto Clough describes listening as a “delicate looping” of comings and passings that “relay between the affective dimension and experience [to] pattern […] an insipient subjectivity.” See Patricia Ticineto Clough, The User Unconscious: On Affect, Media, and Measure (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018), 63.

[4] Ashon Crawley coined this phrase to capture “how worlds take shape in and as feelings” that set “us in various kinds of motion” that “move through us, and as us, even when we don’t ‘know’ ” it. Ashon T. Crawley, Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibility (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017), 90.

[5] CAConrad. Amanda Paradise: Resurrect Extinct Vibration (Seattle: Wave Books, 2021).

[6] The association between internet culture and distraction surfaces across numerous fields from child development to media ecology. For an example of the former, see numerous articles around parenting (particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic), such as Erin Walsh and David Walsh, “Why Digital Distractions Can Make It Harder for Kids to Focus,” Psychology Today, February 18, 2022. In the latter context, see Sherry Turkle’s oeuvre in particular: Sherry Turkle, Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age (New York: Penguin Books, 2015). See also Dominic Pettman’s diagnosis of a substantive change in online distraction in the particular setting of social media: “Distraction is no longer a gesturing away from that which disturbs … It is not to ‘create a distraction’ [from something else] Rather, … the thing designed to distract … has merged with the distraction imperative, so that … representations of events are themselves used to obscure and muffle those very same events.” Dominic Pettman, Infinite Distraction: Paying Attention to Social Media (Malden: Polity, 2016), 11.

[7] While our aims and argumentation are different, this observation follows from N. Katherine Hayles’ (and others’) agenda-setting work reconsidering digital reading practices in terms of different (if often overlapping) modes of attention. See N. Katherine Hayles, How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012).

[8] Writing about distraction in digital culture, William Bogard demonstrates how “in countless forms, [distraction] is implicated in the production of life’s pleasures (the French meaning of the term is close to ‘entertainment’ or pleasurable ‘diversion’).” William Bogard, “Distraction and Digital Culture,” CTheory, October 5, 2000.

[9] Discount, because the destructive pleasure of consumerism is gone. Consumer culture worked via brands to tie purchases to identities, with the specialness of an object standing in for a deeper lack residing in each of us. Today’s internet operates at one step further removed, seeking knock-offs of the things that would fulfill this function, sought after cynically without even the hope that something deeper might be fulfilled (in this light, we appreciate the perversity of Amazon naming their warehouses “fulfillment centers.”)

[10] Cory Doctorow evocatively coined the term “enshittification”—selected as the 2023 Word of the Year by the American Dialogue Society—to capture the tendency of platforms to decline. As he writes, “Here is how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.” Cory Doctorow, “Pluralistic: Tiktok’s enshittification,” Pluralistic: Daily links from Cory Doctorow, January 21, 2023. See, also, the Wikipedia entry for “Enshittification,” (accessed November 7, 2025).

[11] Interrupting barriers to action mimic a form Behar associates elsewhere (in the context of cryptography) with adversarial labor. She defines adversarial labor as “labor understood as computational activities that don’t produce surpluses. Instead, what adversarial labor ‘yields’ is things that don’t yield: structures that exist firstly to stump brains and stub toes, to stand in the way or obscure.” See Katherine Behar, “A GAN. Again. A Nonce. Anon. … And a GPU,” conference presentation at Experimental Engagements, Society for Literature, Science, and the Arts, Irvine, California, USA, November 8, 2018.

[12] One might think that we could simply choose where and whether to respond to an alert, but as we discuss below with respect to Natasha Dow Schüll’s work, this is by no means a simple matter of an agential decisions.

[13] To be clear, the term “abstraction” here refers to the ability (and necessity) of imagining something in its temporal and formal registers, rather than merely atomistically. As such, it is by no means opposed to something like embodied knowledge, but abstraction is instead inseparable from embodiment.

[14] Steve Krug’s best-selling Don’t Make Me Think!, first published in 2000, exhorted web designers to unburden users from thinking. Krug’s “overriding principle” for usability design is that on first glance “a Web page … should be self-evident. Obvious. Self-Explanatory” immediately for anyone who looks at it. See Steve Krug, Don’t Make Me Think (Revisited): A Common Sense Approach to Web and Mobile Usability (San Francisco: New Riders, 2014). Consider the same logic in offline product design, as in the case of “Norman Doors.” Named after usability design guru Don Norman, a Norman Door is any door that is not intuitive to use. If you have ever pulled a door that needs to be pushed, or pushed a door that needs to be pulled, you have encountered a Norman Door. See also the canonical Donald Norman, The Design of Everyday Things, revised and expanded edition (New York: Basic Books, 2013).

[15] Credited as defining the field of ubiquitous computing, Marc Weiser promoted a vision that hinged on invisibility. In his words, “The most profound technologies are those that disappear. They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it.” Along with his Xerox Park colleagues, Weiser strove “to conceive a new way of thinking about computers, one that takes into account the human world and allows the computers themselves to vanish into the background.” See Mark Weiser, “The Computer for the 21st Century,” Scientific American 265, no. 3 (September 1991): 94–104. See also the discussion in Jennifer Gabrys, Program Earth: Environmental Sensing Technology and the Making of a Computational Planet (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016). Note that for others like Wendy Chun, this emphasis on invisibility and transparency is a symptom of the inverse: “The current prominence of transparency in product design and political and scholarly discourse is a compensatory gesture.” See Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, “On Software, or the Persistence of Visual Knowledge,” Grey Room 18 (Winter 2004): 27.

[16] Friedrich A. Kittler, “There Is No Software,” in The Truth of the Technological World: Essays on the Genealogy of Presence (Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2014), 219–29. See also Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, “Hardware/Software/Wetware,” in Critical Terms for Media Studies, ed. W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark B. N. Hansen (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 186–98.

[17] Wendy Chun explains how political and subjective inequities persist in software, writing that “software perpetuates certain notions of seeing as knowing, of reading and readability that were supposed to have faded with the waning of indexicality. It does so by mimicking both ideology and ideology critique, by conflating executable with execution, program with process, order with action … The knowledge software offers is as obfuscatory as it is revealing.” Chun, “On Software, or the Persistence of Visual Knowledge,” 27–8. For her more recent work on this subject, see Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Discriminating Data: Correlation, Neighborhoods, and the New Politics of Recognition (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021).

[18] To be fair, broken links and 404s were probably more common in the 1990s, but for us the explicitness of these malfunctions was less frustrating than the current interruptive postponements. That is, broken links were unintentional, whereas contemporary interruptions are obnoxious because they are designed to be that way.

[19] Or is it externalized? The material status of tinnitus is highly contested, and in many respects inseparable from the (often for-profit) medical and para-medical industries in which it is managed. Notably, in most cases tinnitus seems to be a psychological phenomenon insofar as the ringing is not audible to others and can be aggravated by, for example, worrying about it. And yet, the tones can also (sometimes) be treated by techniques using physical phenomenon including “masking” tones. See Mack Hagood, Hush: Media and Sonic Self-Control (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019).

[20] Shane Denson uses the term “discorrelation” to describe the way that contemporary technologies emphasize the gap between sensation and experience, most notably in the case of the severing of images from perception that occurs through computational processes. See especially Discorrelated Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020) and Post-Cinematic Bodies (Lüneburg: Meson Press, 2023).

[21] Parsing a shift from disciplinary society to control society, Gilles Deleuze notes that “in the societies of control one is never finished with anything—the corporation, the educational system, the armed services being metastable states coexisting in one and the same modulation, like a universal system of deformation. […] In the societies of control … what is important is no longer either a signature or a number, but a code: the code is a password … The numerical language of control is made of codes that mark access to information, or reject it. We no longer find ourselves dealing with the mass/individual pair. Individuals have become ‘dividuals,’ and masses, samples, data, markets, or ‘banks.’ ” Gilles Deleuze, “Postscript on the Societies of Control,” October 59 (1992): 5.

[22] Denson describes a “strange self-displacement […that turns] itself and the world into a weird volumetric ouroboros.” Denson, Post-Cinematic, 64.

[23] Cage famously declared that “there is no such thing as silence” after his 1951 experience in an anechoic chamber, during which he could hear internally generated comments. Subsequent to this, he maintained the position that seeming emptiness is full of activity and movement. For an account of Cage’s evolving poetics of silence, see Eric De Visscher, “‘There’s No Such a Thing as Silence…’ John Cage’s Poetics of Silence,” Interface 18, no. 4 (1989): 257–68.

[24] In her study of machine gambling in Las Vegas, Natasha Dow Schüll asks after “the technological conditions by which interaction turns into immersion, autonomy into automaticity, control into compulsion.” This set of transformations takes place when gamblers enter “the zone” which Dow Schüll describes as “a state in which alterity and agency recede.” Necessarily, the zone’s “turn to automaticity” presents a conundrum for interaction design: “Designers’ struggles to make sense of machine gambling when there no longer seems to be an agent at the controls of the game—that is, when play becomes ‘autoplay’—rehearse the conflict between their rhetoric of stimulating entertainment and players’ preference for the rhythmic continuity of the zone.” See Natasha Dow Schüll, Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 168–77.

[25] Dow Schüll recounts gamblers soaked in their own vomit and urine and even falling into a diabetic coma (Dow Schüll, 179). The uninterrupted absorption of play distracts gamblers from their own bodies such that “the most extreme of machine gamblers speak in terms of bodily exit.” (174). Just as a gambler’s bodily agency recedes, so too does the “alterity” of the machine, such that in the zone, the interface separating body from machine evaporates and the two become one: gamblers’ “own actions become indistinguishable from the functioning of the machine.” In our context, we note that gamblers’ preference for this type of suspended immersion where awareness recedes is precisely at odds with the economies of interruption we are describing in contemporary online experience. For example, Dow Schüll describes how casinos launched innovative programs that aimed to entice gamblers only to fail by interrupting their play. These programs failed to recognize that the goal should be to keep gamblers in the zone, an “experience … characterized not by stimulation, participation, and the gratification of agency but by uninterrupted flow, immersion, and self-erasure” (170–71, italics added).

[26] See Wayne Perry, “Super Bowl Bets Placed Online Surged This Year,” PBS News, February 12, 2024, and “The Evolution and Rise of Mobile Betting,” Uplatform, June 20, 2022.

[27] In historicizing the exploitation of attention in contemporary technoculture, Jonathan Beller argues that “we have entered into a period characterized by the full incorporation of the sensual by the economic. This incorporation of the senses along with the dismantling of the word emerges through the visual pathway as new orders of machine-body interface vis-à-vis the image. All evidence points in this direction: that in the twentieth century, capital first posited and now presupposes looking as productive labor, and, more generally, posited attention as productive of value.” Jonathan Beller, “Paying Attention: The Commodification of the Sensorium,” Cabinet Magazine 24 (Winter 2006–2007).

[28] For Denson, discorrelation leads to a generalized interchangeability that “follows from processes of desubjectification and dividuation, which facilitate the human’s insertion into the technical system and effect the hollowing out and replacement of affective life with the microtemporal rhythms of the machine.” Denson, Discorrelated Images, 185.

[29] Notably, calling a restaurant is an audible practice, which may partially explain why so many people have become uncomfortable making phone calls—we want phones to be silent devices. Moreover, the rogue move of a telephone call operates outside of the tightly scripted grammars of action that code behavior in an appified world. As Phillip Agre asserts, “grammars of action” begin by designing technical systems modeled on social systems, but ultimately rechoreograph social systems to make them legible to technical systems, such that the grammar brings the two into accord. See Phillip Agre, “Surveillance and Capture: Two Models of Privacy,” The Information Society 10, no. 2 (1994): 101–27.

[30] Through the concept of “grammars of action,” Agre demonstrates how technical systems that are initially developed to facilitate an existing social activity ultimately end up shaping that activity in ways that pervert it to accommodate the logic and limits of the technology. Often, this is because a measurement is taken to stand in for that which it measures, which Agre explains as a “capture model” of privacy practices.

[31] As Jodi Dean argues, “values heralded as central to democracy take material form in networked communications technologies,” but in doing so any particular contribution “need not be understood; it need only be repeated, reproduced, forwarded.” As Dean concludes, this means that “circulation is the context.” Jodi Dean, “Communicative Capitalism: Circulation and the Forclosure of Politics,” Cultural Politics 1, no. 1 (2005): 59.

[32] Bodies are never isomorphic with themselves: the boundaries of our legal bodies are different than (if caught up in) our political bodies (see the difference between anti-abortion laws and anti-protest policing), just as the boundaries of biological bodies have a complex relation with embodied experiences of the possibility space of decision-making. For better and worse, addressing this has been a central promise of sound studies insofar as sound constitutively complicates the very notion of a boundary. In this context, the concept of listening can keep us in touch with the vagaries of our new ecology: to ask after a change in technology—to listen away from the pings of consumer tech in favor of the rhythms and distributions of complex relations—is to ask after how such boundaries are maintained and breached in a given episteme.

[33] “That the ubiquitous theoretical language about the body did not touch my own body provoked a nagging question for me, propelling me into a zone of nonbeing, as Franz Fanon calls it, in which the body is named, referenced, and yet predominated by a form of conceptuality that rejects and anesthetizes sensation. Embodiment goes beyond the question of what the body is able or unable to do. After one too many seminars in the academy where I felt not a single audible breath upon my skin, I came to see that it doesn’t matter how much you talk about the body, theorize it, how much you stitch together the psyche with the political at that level of abstraction. If perception and sensation are not part of that effort, the result is a schism that leaves radical knowledge even more vulnerable to commodification and capture. When theory does not find a language for tracking the perceptual shifts that conceptuality calls for, rather than merely describing those shifts, theory reinforces its own separation from life.” Anita Chari, A User’s Manual to Claire Fontaine (Milan: Lenz, 2024), 13.

[34] Put differently, what is meaningful is dictated from within the workings of a bureaucratic system, and is thus indifferent to actions outside of it. As David Graeber demonstrates, within a bureaucratic system the “algorithms and mathematical formulae by which the world comes to be assessed become, ultimately, not just measures of value, but the source of value itself.” David Graeber. The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy (Brooklyn: Melville House, 2015), 41.

[35] Consider, for example, Deleuze’s brief analysis of Kafka’s The Trial where he situates the story at the pivot between disciplinary society and control society, with the former acting through the “apparent acquittal […] between two incarcerations” and the latter characterized by “limitless postponements” in continuous variation. See Deleuze, “Postscript on the Societies of Control,” 5.

[36] This psychology and aesthetic are perfectly captured in a short novel by Georges Perec. See Georges Perec, The Art and Craft of Approaching Your Head of Department to Submit a Request for a Raise, trans. David Bellos (New York: Verso, 2011).

[37] Shoshana Zuboff demonstrates in clear and accessible language how digital surveillance has emerged as an unprecedented new market form and what the consequences of this are. See Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: Public Affairs, 2019).

[38] The pernicious practices involved in this “trade” ought to give us pause, particularly as technologies that compromise privacy are often debuted through testing on disproportionately vulnerable populations. For example, Virginia Eubanks has shown how many problematic privacy-infringing technologies have been developed in the context of social and governmental programs that interface with the poor—a population that frequently has no alternative but to compromise their privacy in order to attain access to crucial social welfare programs, or that is disproportionately criminalized by automated processes deployed by state programs. As Eubanks explains, “Marginalized groups face higher levels of data collection when they access public benefits, walk through highly policed neighborhoods, enter the health-care system, or cross-national borders. That data acts to reinforce their marginality when it is used to target them for suspicion and extra scrutiny. Those groups seen as undeserving are singled out for punitive public policy and more intense surveillance, and the cycle begins again. It is a kind of collective red-flagging, a feedback loop of injustice.” See Virginia Eubanks, Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor (New York: Picador, 2018), 6–7. Similarly, Ruha Benjamin has exposed how in “everyday contexts … emerging technologies” are “often [employed] to the detriment of those who are racially marked.” This is especially the case for technologies that profess to be “colorblind” but collect data that serve as proxies for discrimination, amounting to what she calls a “New Jim Code.” That is, “technologies [that] pose as objective, scientific, or progressive, too often reinforce racism and other forms of inequity.” See Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (Medford: Polity, 2019), 2.

[39] Eric Cazdyn captures this perfectly through his relation to life-saving drugs, which put him in a position where his political loathing of pharmaceutical companies (based on the exploitative practices that they deploy at every level) coincides with his appreciation that pharmaceutical drugs allow him to continue living. (Ironically, Fugazi—noted activists against the unjust distributions of the recording industry—just came onto my automated Spotify mix as I was typing this.). Eric Cazdyn, The Already Dead: The New Time of Politics, Culture, and Illness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012).

[40] As Denson notes with respect to digital cinematic images, when images are severed from our perception (by virtue of processes that are materially and constitutively alien to human perception by virtue of their speed and scale), “it is our consciousness or sensation that becomes the immediate target of dividuation.” Denson, Post-Cinematic Bodies, 58.

[41] We are grateful to Andy Graydon for this felicitous formulation.

[42] Such a purely transactional internet lacks the libidinous thrills of consumerism.

[43] See Sylvère Lotringer, “The Dance of Signs,” in Hatred of Capitalism: A Reader, ed. Chris Kraus (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2001), 173–90.

[44] Thomas Mullaney uses the term “hypography” to describe the process of writing in Chinese on computers. Briefly, Chinese computer users have for many years typed with software interfaces that resemble “autocomplete” in their presentation of a list of options based on limited partial inputs. There are several software programs for this that are commonly used, and they differ dramatically from each other. Unlike the linear approach used in autocomplete (i.e., where one progressively enters the letters of a word from start to finish), these software interfaces allow much more complex allusions: one might, for example, do the equivalent of typing “zz” to start the word “pizza,” as the rarity of this letter combination will produce a short enough list of options from which to select the word (which is done by typing the appropriate number). Crucially, this process in combination with the number of software programs in circulation and the variance between them means that it is unlikely that any two users will type the same keystrokes to type the same word. See Thomas S. Mullaney, The Chinese Computer: A Global History of the Information Age (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2024).

[45] We are certainly not arguing that silent smart phones inaugurated interruptive socialities, but rather that they amplify them and thereby bend them into new and newly prominent forms.

[46] While clicktivism is often understood as the internet version of “slacktivism” (which was coined in the mid 1990s) the use of Google Ngrams reveals that use of the latter increases dramatically as the internet has become more quotidian. Indeed, use of the term increases steadily through the 2010s and peaks during the Covid-19 lockdowns of 2020. In this sense, clicktivism constitutes the most robust form of slacktivism, rather than being a minor variant of it. The results of the Google Ngram query can be viewed here (accessed November 7, 2025).

[47] Ten years ago, Gregory described how this asocial totality was already “pressured” by the ways “we have become deeply entangled in one another” through data’s ubiquity, which puts us into “a ‘weird solidarity’ with one another.” Specifically, Gregory noted how “automation, in tandem with big data and ubiquitous computing, promises a form of personalized care that is actually predicated on the participation of a much larger and abstract social body. In the production of these massive data sets, upon which the promise of “progress” is predicated, we are actually sharing not only our data, but the very rhythms, circulations, palpitations, and mutations of our bodies so that the data sets can be “populated” with the very inhabitants that animate us.” See Karen Gregory, “Big Data, Like Soylent Green, Is Made of People: A Response to Frank Pasquale,” Digital Labor Working Group, November 1, 2014.

[48] Collected data is used to “construct diagrammatic abstractions of features common in [the data], and gather these localized abstractions into predictive statements” that may or may not be legible to human users. Adrian MacKenzie and Anna Munster, “Platform Seeing: Image Ensembles and Their Invisualities,” Theory, Culture & Society 36, no. 5 (2019): 17.

[49] Robin James demonstrates that, in our present episteme, “acoustically resonant sound is the ‘rule’ [that] otherwise divergent practices use ‘to define the objects proper to their own study, to form their concepts, to build their theories.’ ” “This rule is the qualitative version of the quantitative rules neoliberal market logics and biopolitical statistics use to organize society.” In this way, “the sonic episteme misrepresents sociohistorically specific concepts of sound” as though they were natural, and then “uses sound’s purported difference from vision to mark its departure from what it deems the West’s ocular- and text-centric status quo.” This episteme remakes and renaturalizes the white supremacist political baggage inherited from Western modernity “in forms more compatible with twenty-first-century technologies and ideologies.” Robin James, The Sonic Episteme: Acoustic Resonance, Neoliberalism, and Biopolitics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 3–5.